|

JOINT BOOK REVIEW, from Thesis 11, 2007

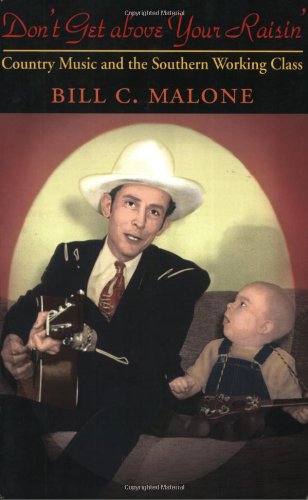

Singing Australian: A History of Folk and Country Music, by Graeme Smith (Pluto Press, Sydney, 2005) Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’: Country Music and the Southern Working Class, by Bill C. Malone (University of Illinois Press, Champaign, 2006) |

|

When the Academy finally discovered that popular music and culture might be a useful measure of history and society, it was like a dam wall breaking. The problem was that fashionable obscurist deconstruction became the orthodoxy. That’s why Australian music studies has given us too much information on current local hip-hop, say, because it ticks the correct boxes – post-modernism, globalism, multi-culturalism – and this at the expense of fast-disappearing histories! Happily, Graeme Smith’s Singing Australian avoids a number of these sins. Ultimately though, it still frustrated me. Maybe the fault is mine. In criticism I am crucially aware of not complaining an apple isn’t an orange. But reading Singing Australian, despite its assets, I couldn’t help feeling the opportunity was lost to offer a more comprehensive narrative history, for which the field still begs. I know, I know, it is a personalised work, the author admits as much. And where it is most directly personal, on the first folk revival of the 50s, it is at its strongest, with Smith able to convincingly flesh out the detail – and be assured, Singing Australian is rich in research and hard information. But I am still left wondering if this personalisation might not explain some of the book’s more glaring omissions. Singing Australian is broken into three sections – ‘Folk’, ‘Country’ and ‘Crossing Borders’ – which suggests a certain structural integrity itself; it is about the different ways music scenes have projected an idea of Australia or Australians, ie the old national identity thing, and how it’s changed over the last fifty years. To the book’s credit, it is eminently readable. Largely free of jargon, Smith’s prose is clear and straightforward, and canters along at nicely accessible pace. Where it breaks down a bit for me though, first of all, is the way the tone and approach changes, from being so highly personal in the first section to much less so in the other two. Of course this is only honest, but it does jar. What also muddies the waters a bit is the way that in the resolution of the last section, it’s not only folk and country that cross each other’s borders but old ethnic genres that have arrived on the scene, not to mention new hybrid world music. Again, I know the book would be remiss without some acknowledgment of the folk musics of newer migrants, but I felt it was already dropping balls in the Anglo-Celtic folk-country juggle as it was. Ultimately, Singing Australian comes across as a potted history that’s just too potted. Like it’s an old folkie, which music academic Smith unabashedly is, trying to convince other old folkies that country music, which they always disdained, was actually always part of the folk tradition – and that now it’s all melted into an even larger amorphous musical stew anyway. Smith does well to distance himself from the gross limitations the left imposed on folk music when it revived it in the 50s, but even at the end of the first section I was still left wondering, Who were the major artists? and/or, apart from Reedy River, what were the major works or songs? and what was their impact? This section of the book is less about music, songs and performers themselves, than the way the left seized upon a movement as a potential tool of its own ideologies. The left selectively pushed that which suited it and rejected the rest (not only country but also jazz, which was apparently elite and decadent); what is extraordinary here is that Smith manages to repeat the same mistake. The Seekers, for example, are brushed aside in a couple of lines, and even if they were squeaky-clean Young Liberals, surely Gary Shearston, Doug Ashdown, Jeannie Lewis or Eric Bogle would warrant more detailed examinations? Jeannie Lewis doesn’t even get an index entry, and neither does Warren Fahey, Marion Henderson, Wattle Records or Fahey’s seminal label Larrikin Records. I’m sorry, but I don’t know how you can write this history without those elements and more than a few others in place. In the second section, Smith puts the heathen view that “textual and melodic echoes of earlier folk forms can be heard in many songs of early Australian country singers. That this was so seldom recognised or acknowledged by the first folk revival folk collectors reflects their intellectual goals,” and he traces the way country music picked up the dying traditional folk imperative – what became in Slim Dusty’s hands the (neo) bush ballad. Smith investigates the way both folk and country had to deal with rock when it came along, but really only cursorily, and this, to me, is where the book really starts to go awry. Because it was in the way that country, rock and folk fused (into pop) during the 60s’ cultural revolution that, to me – calling an apple an orange? – marks a tidier resolution of this book’s first two sections. In the country section, after passing relatively quickly over the holy trinity of Tex (Morton), Buddy (Williams) and Slim, Smith concludes with stand-alone profiles, or case studies, of John Williamson, Lee Kernaghan, Troy Cassar-Daley and Kasey Chambers. Section three opens boots and all with a chapter called ‘From multi-cultural to world music’, after which it goes (back) to one called ‘Between folk, country and rock’ – which is where, I would have thought, the above quartet really belong. In between, too, Smith seems to take things far too literally, and so the way folk and country influenced the maturation of Australian pop-rock songwriting, from the Dingoes and Chain to Skyhooks to Cold Chisel to the Go-Betweens and Triffids, is all but completely overlooked. Paul Kelly of course gets the usual guernsey, but do we really need a profile of Roaring Jack when, say, Kev Carmody and Archie Roach are both treated as sub-sets of Paul Kelly? The emergence in the 80s of ‘new country’ and folk’s ‘new traditionalists’ was full circle, in a way, for these genres, but to conclude with a nod to new age designer didgeridoo music is a slap in the face to the roots and a blind eye to the vitality of on-going alt.country and nu folk and folk-tronica. In contrast, Bill Malone’s Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’ is exemplary in almost every respect, from its beautiful cover and design to its unfailingly erudite text to its extensive discography (another feature Singing Australian is crying out for). So much of it is so good that if it’s flawed, it’s not fatal. Malone is a writer I’ve admired for some time, a Texan academic historian and the author of many books stretching back to his 1968 debut Country Music USA, a groundbreaking work then and still essential now. His only rivals are Charles K. Wolfe and maybe Nick Tosches. Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’ is an examination, through history spanning the whole last century, of the way country music was born of the American South and, even as it is now internationally commodified, how it remains a true voice of the working class. Country music is an absolute repudiation of the old folkies’ crusty belief that commercialisation or any outside interference is necessarily corrupting. When the left co-opted grass-roots folk in the 50s, it became a music of the urban intelligentsia. But no matter how hard the record business has sold country music, how much more ‘sophisticated’ or blander Nashville has packaged it up, it remains staunchly working class; as Graeme Smith might put it (not me), terminally uncool. The left rejected country music because its working class essence wasn’t appropriately revolutionary. But even if country music is politically reactionary, Bill Malone takes it as he finds it. Writing history to an agenda is doomed to be as unsuccessful as making music on the same basis; the thesis is shaped to reflect the fieldwork, not vice versa. Malone tackles his subject by themes, as he puts it “home, religion, rambling, frolic, humour and politics,” convincingly illustrating how the music and life are inseparable. His approach is objective if illuminatingly (and consistently) personally tinted, and he gives greater power to his arguments with the way he can inject a contemporary example into his historical narrative, thus proving the traditions are still alive and relevant. But there is one gaping hole: Love and death. Drinking might be another, but drinking permeates two sections as it is – ‘rambling’ and ‘frolic’ – and maybe Malone felt that love and death are similarly such intrinsic themes that they emerge anyway. And to an extent they do. But to me, this would have made the perfect final chapter. Meantime check the ‘Dead Kids and Country Music’ and ‘Ten Best Cheatin’ Songs’ sections of Martha Hume’s You’re So Cold I’m Turning Blue, or the sex and murder sections of Nick Tosches’ Country: The Biggest Music in America, ‘Stained Panties and Course Metaphors’ and ‘You’re Going to Watch Me Kill Her’. It’s a shame the literature of our own roots music doesn’t run so deep as to allow a reference to cover the shortfalls of Singing Australian. |