The Bodgie Boogie: WHAT WAS the first australian ROCK&ROLL RECORD?

|

This piece was first published in Meanjin magazine, under the title "Before the Big Bang," in 2006, and then in 2012, somewhat to my astonishment, it was reprinted in the Meanjin Anthology, edited by Sally Heath and published by Melbourne University Press (BUY a copy here). I would contend it's still the first piece to seriously try and address this burning question...

|

|

It is, of course, the oldest parlour game known to trainspotters of the popular music variety: What was the first rock’n’roll record? Was it Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” (1955)? Or was it something much earlier (and blacker), like Ike Turner and Jackie Brenston’s “Rocket 88,” of 1951? – or even earlier, like Wynonie Harris’s “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” of 1948? Or was it six years after that, in ’54, when Elvis covered “Good Rockin’ Tonight” as one of his first releases on Sun Records?

|

|

It is one of the great conceits of the rock generation that, as John Lennon once put it, “Before Elvis, there was nothing.” But of course it was never as if there was a brick wall running down the middle of the 50s. Orthodox American cultural history now sees that rock’n’roll was a form that evolved after the second world war in an explosive confluence of technology and economic and social necessity, a teen-suburban fusion of a number of grass-roots traditions.

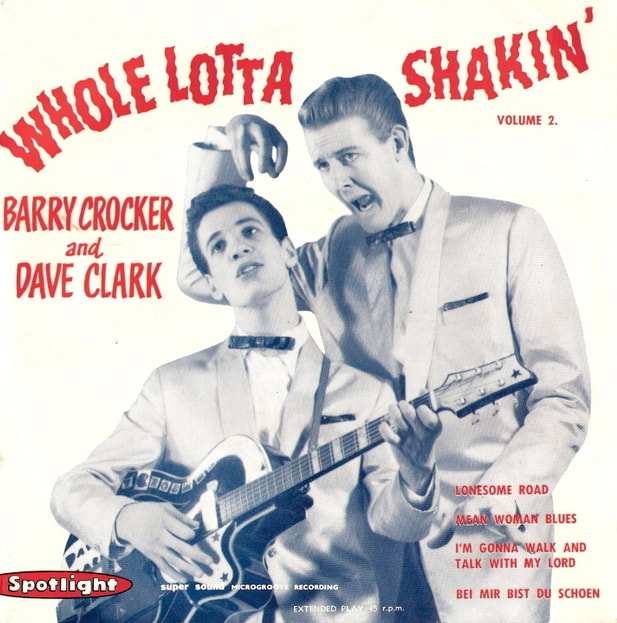

Even in tiny, isolated Australia, rock’n’roll didn’t emerge out of a vacuum, as the orthodox rock-critical reading has tended to have it. I am myself as guilty as anyone of propagating the myth that Australian rock’n’roll was born fully of a cargo cult. And so as much as anything, that’s why I’m here now, attempting to answer the question, What was the first Australian rock’n’roll record? – in order to correct my own mistakes! Post-war/pre-rock’n’roll popular music in Australia is under-examined. Both our jazz and country music histories take a fairly purist view of their genres, disregarding the edges where they may stray or cross over into the dreaded shallow waters of commercialisation. That’s why I’m here now, with post-modern disdain for ‘authenticity’: To try and find out how a transition was made, to plot the way existing local traditions fed into the birth of rock’n’roll in this country, to locate the ‘tipping point’… In its popularisation (which in one way defines it), rock’n’roll became greater than the sum of its parts. Which is why it’s an over-simplification to say it was just white ripping off black – just as it is to say Australia simply aped America. Australia, like the rest of the world, was copping American music (‘conducting a dialogue’ with it) long before rock’n’roll came along. With more purchase than others on the 20th Century’s new American modes (not least of all because we too were English-speaking), Australian rock’n’roll began much the same way the Beatles did in Liverpool, picking up on American records and putting them through a local cipher. There’s no doubt that Johnny O’Keefe was the Big Bang of Australian rock’n’roll. After Bill Haley and his local Festival Records release of “Rock Around the Clock” hit huge in 1955/’56, JOK was the first local act literally capable of sharing a stage with such American invaders, and in January, 1958, when he recorded “The Wild One,” he could quite reasonably lay claim to having cut the first truly great and certainly the first hit Australian rock’n’roll record. The status of “The Wild One” is beyond reproach. It is one of the few Australian tracks of its era that has survived as an all-time classic (certified by covers of it from Buddy Holly to Iggy Pop), and uncannily it was one of the few original local compositions of the era. But the road that led to “The Wild One” is dotted with ostensible rock’n’roll records, many of whose claims on various first-doms are also legitimate. By 1956, when rock’n’roll had the name – by which time it was also widely tipped to quickly die – Australian record companies were jumping on the fad. A couple of records, 78rpm singles, released in late 1955/early ’56, have vied for the title of Australia’s first rock’n’roll waxing. Vic Sabrino’s Pacific Records’ single of the period, which coupled a version of “Rock Around the Clock” with ”Magic of Love” (PB115), is a more likely contender than a roughly contemporaneous single Richard Gray cut for Philips, which coupled versions of Chuck Berry’s “Mabellene” (sic) with Fats Domino’s “Ain’t That a Shame” (P37031H ), because, in a word, it’s a much better track, which at least swings if not rocks. |

|

And yet at the same time, Les Welch, the man who could be called Australia’s great anticipator of rock’n’roll, if not its godfather, was releasing sides that marked a pinnacle of a career that began in the 40s and flourished until it was, in so many ways, overtaken by rock’n’roll – might it not be reasonable to posit some of his last great records as our first rock’n’roll records? Or even some of his early records?

Certainly, somewhere between Les Welch and the Wild One – supported by a cast of lesser characters including some of the darkest stars of forgotten Australian music history, names like Vic Sabrino, Nellie Small, Edwin Duff and Ned Kelly – local rock’n’roll coalesced. Rock’n’roll was rustic country, blues and jazz crashing into the new suburban world of post-war affluence, of cars, electric guitars, TV, vinyl records, and transistor radios. Before and after the war, EMI had a virtual monopoly on the recording industry in Australia. But with the influx of even more things American during the war – including, especially, music and fashion – and with the economic and baby boom after the war, everything began to change. EMI had always had a relatively active local recording program. After the war, in the wake of Tex Morton, it recorded more hillbillies, like Slim Dusty, and it even started recording jazz. But in the 1950s, just as Holden’s monopoly of the car market would be broken in the 60s, EMI’s music monopoly was broken. In the fifteen years from the end of the war to 1960, Australia was not only colonised by foreign majors like Philips (later PolyGram, now Universal), CBS (now Sony), Warners and RCA (later BMG, now merged with Sony), but also, just as happened in the US, it spawned a groundswell of regional independent labels, whether jazz or country specialists or major challengers like the Australian Record Company (ARC), Festival, Astor and W&G. And it was these labels – everybody but EMI! – that fostered early rock’n’roll. EMI’s complacency allowed the new operators in. As a prime example, it was only after EMI let its local option on “Rock Around the Clock” lapse that Festival Records’ co-founder and Musical Director, the ubiquitous Les Welch, pounced on it, sealing the still-fledgling label’s future. EMI wouldn’t catch up again till it poached the Seekers from W&G in the 60s. Off the back of local rock’n’roll, Festival would become ‘the Australian major’ (acquired by Rupert Murdoch in the 70s and only recently, after buying up Michael Gudinski’s Mushroom, sold to Warners.) Festival was born in 1952 after Les Welch left the Australian Record Company looking for new opportunities. ARC had been founded by George Aitken in Sydney in 1948, after the model of successful new US independent Capitol, which was home to Nat King Cole and Frank Sinatra. ARC divided to conquer, with two distinct in-house sub-labels, Rodeo and Pacific, Rodeo for country music (Reg Lindsay), and Pacific, under the direction of Les Welch, for pop and jazz. Welch is the Invisible Man of Australian music, not just the godfather of Australian rock’n’roll but also, virtually, of the entire modern Australian record business, a once-huge star and industry innovator who, though he is still alive and living in Sydney, remains a frustrating enigma. At Pacific, he cut hundreds of sides, whether his name was on the label or not, producing himself and feature vocalists on a wide array of jazz, pop, country, novelty songs, R&B – a bit of everything. As a performer he was a man who could be billed, in 1948, our King of Swing, and in ’57, our King of Rock’n’Roll. “Welch’s importance to Australian popular music during the post-war decade was enormous, but for various reasons has proven difficult to document,” Bruce Johnson, author of Oxford Companion to Australian Jazz, wrote in 1999. “Welch was a pioneer singer and pianist in the blues/R&B style, one of the most convincing early Australian exponents of the approaches that modulated into rock.” |

|

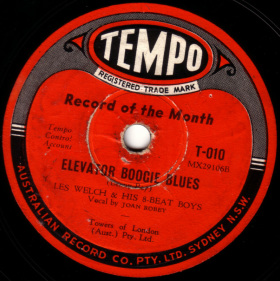

Welch’s first formal release under his own name was “Elevator Boogie Blues/Cigareets and Whusky and Wild Wild Women,” which he recorded for the short-lived Tempo label in 1949. His first actual appearance on shellac had come two years earlier, when he took the vocal on the Ellerston Jones Quintet’s Kinelab label recording of “Rhythm Club Shuffle,” which is a way cool exercise in beatnik jive a la Slim Gaillard: This was certainly the beginning of something right here.

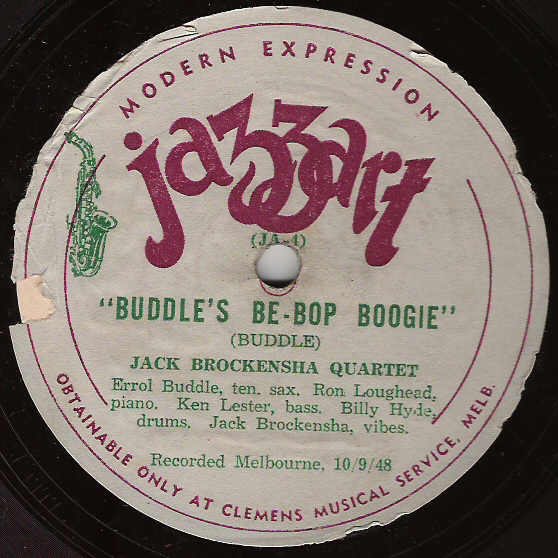

Like other, mostly-modern Sydney jazzmen like Charlie Munro, Don Burrows and Wally Norman, Welch cut his teeth playing (underage) for US servicemen during the war. After the war, Ellerston Jones, who was a tastemaker with his own column in Music Maker, bought all these men together in search of a ‘rhythm’ style, as nascent R&B/jump blues was then commonly called. It was all about dancing. If one thing hadn’t changed since the war, it was that people wanted to dance. That’s why trad jazz enjoyed such a huge boom in Australia in the late 40s/early 50s, because it was raging, stomping dance music. If this was jazz going sort of backwards, jazz was also going forwards, into the modern. But modern jazz was for listening, not dancing, and as such claimed a much smaller audience. And that’s why so many modernist Australian jazzmen moonlighted in rhythm bands, and later rock’n’roll bands, which was the great bolstering of it all – because it was a way to make a quid, and it was blues-based dance music with a modern, urban edge. “R&B was a hybrid form,” wrote legendary Greek-American bandleader Johnny Otis. “By '48 or '49, it was set - we had an art form, though we didn't know it then... It surely wasn't big band; it wasn't swing; it wasn't country blues. It took over all the things that made R&B different from big band swing: the afterbeat on a steady four; the influence of the boogie; the triplets on piano; eight-to-the-bar on the top hat cymbal; and the shuffle pattern of dotted eighth and sixteenth note. It was the foundation of rock’n’roll." In Australia, the rhythm style followed on from boogie woogie. Les Welch himself started out as such a solo pianist. After the war, the country was gripped by boogie fever. In 1948, the year before Welch’s “Elevator Boogie Blues,” Ron Falson’s Liberty Seven and Warren Gibson’s Metronome Orchestra both cut Gene Krupa’s “Boogie Blues” (for Liberty and Marconi respectively). For Jazzart, Edwin Duff cut Erroll Buddle’s “Be-Bop Boogie” with Jack Brockensha’s band. This was music for a new audience, as Ellerston Jones wrote in defence of bobbysoxers in his ‘Rhythm Club Corner’ column in Music Maker in June, 1948 (in the process eerily foreshadowing rock’n’roll): “Most people know that changing times bring about changing conditions… Teenagers are in an unenviable position – they are influenced and confused by their reactions when they attempt emotional adjustment in an ever-changing world… Bobbysoxers are reasonably clean-living, happy-go-lucky young people who have found in modern music and what goes with it a ready-made means of self-expression. To them music and jiving is a common language they can all speak fluently.” Whenever asked what his sets consisted of, Les Welch, our original Boogie Man, would say, “A fast blues, a slow blues and a boogie.” The first and last are much the same thing. Recognised at the time (October, 1949) by Music Maker as an “exceptionally interesting disc,” “Elevator Boogie Blues” was a landmark that broke all Australian sales records. Covering Mabel Scott’s US R&B hit on one side and a Sons of the Pioneers’ country and western hit on the other, the single set a pattern Welch would repeat many times. A few years later, Sam Philips at Sun Studios in Memphis would apply to same formula to Elvis Presley. As a result of this debutante success, Welch was effectively head-hunted by the newly-formed ARC. There, at Pacific, he set up a virtual hit factory that turned out Australian cover versions of American hits unavailable in this country due, again, to EMI’s inertia in taking up its own local license options. As well as churning out records of every stripe under his own name, Welch supervised the sessions of singers like, say, Edwin Duff, who was a bobby-soxer idol in his own right. Duff anticipated the extravagance of rock’n’roll. If Johnnie Ray was the missing link between Sinatra and Elvis, Duff has to be counted as part our rock’n’roll development too. In part due to his hysterical stage age, Johnnie Ray’s sexuality was always in question, but with Edwin Duff there was no doubt about it. Duff was a conspicuously queer jazz singer with a penchant for outrageous suits and stunts, and he set a hipster tone at the turn of the decade with sides like “You Came from Outer Space,” for EMI, before going over to Pacific for “Rockin’ Chair” and “Saturday Date” with Jack Brokensha’s band. Les Welch himself, with the help of house arranger Wally Norman and often with singer/drummer Larry Stellar, recorded smooth commercial sides like “Mona Lisa,” Rosetta,” “My Foolish Heart,” and “Lucky Old Sun;” novelty songs (like “I’ve Got a Lovely Bunch of Coconuts”), and trad. and modern jazz (“Caravan”). But best were the rhythm records, “A Little Further Down the Road Apiece,” “Jungle Jive,” “Saturday Night Fish Fry,” “Dupree Blues,” “Castle Rock,” “Hambone.” “Then on the B-side,” recalled Wally Norman, “they’d put a jam or a local composition that let them blow off” – something like “Kings Cross Boogie,” “Pacific Boogie Woogie,” or “Rockin’ Boogie.” Though he never recorded as a leader himself, Wally Norman was a key figure in Australian jazz as a trombonist, arranger, agent and writer. Norman served an apprenticeship as part of George Trevare’s historic 1944 Regal-Zonophone session at EMI’s Homebush studio that is generally regarded as Australia’s first hot jazz recording. When he arranged “Jungle Jive” for Les Welch in 1951, all he had to do was refer to the version he cut with Trevare in ’45. With EMI dithering on taking up license options on proven international hits, Welch got Norman to transcribe the arrangements from recordings he’d procured one way or another. Publishers like Alberts encouraged the practice because their songs wouldn’t otherwise get released. “So I did that,” Norman said, “note for note, with the same instrumentation, because there was no copyright, and then we recorded a lot of those, under the Les Welch banner. We would clone these American recordings and release them on the Australian market, to keep the youngsters up with the popular hits from overseas.” In 1952, when ARC picked up its role model Capitol’s local license (thus a source of original hits), Welch left the label and helped form Festival under the ownership of the Mainguard merchant bank; he was replaced at ARC by the label’s public relations man, French bandleader Red Perksey. Welch cut the first Festival release, a version of the current US hit “Meet Mr. Callaghan,” a 78 on the Manhattan label with Pamela Jopson singing, but more pertinent was his Tempos De Barrelhouse, the first (10” 33rpm) album made in Australia. Released at the end of 1952, the album had a foot in both the trad. and rhythm camps, with tracks like “St.Louis Blues,” and “Snatch and Grab It.” Up to 1954, Welch continued to churn out the hits, whether slick ‘commercials’, trad jazz and or more contemporary rhythm fodder like “Flying Saucers” and “Green Door.” He released an EP called Saturday Night Fish Fry that included his second version of the title track (a Louis Jordan original), plus his second version of “Darktown Strutters Ball,” this time with the legendary Norm Erskine on vocals. With his Dixie Six, he even cut a trad. jazz version of Hank Williams’ “Jambalaya,” which only goes to show how blurred the generic boundaries could become. Like the Teddy Boy in the UK, the Australian bodgie emerged after the war as a response to all the Americana he had experienced first-hand during the war. Jitterbug and jive gave way to – what? a sort of Bodgie Boogie? It was all about dancing, and dressing sharp. “Bodgies were listening to jazz,” says John Greenan, who, you suspect, was one himself before he played sax in Johnny O’Keefe’s Dee Jays, and co-wrote “The Wild One.” “It was the thing, you know. To be cool you had peg trousers and wide shoulders and the correct haircut, whether it be a crewcut or slicked-back, and you’d go jitterbugging. But they jitterbugged to big band dance music.” |

|

“Well it was actually just starting to die, the big band thing,” says Bill Gates, a DJ who started out in Sydney in the early 50s and eventually encouraged the very young Bee Gees up in Brisbane, “but these people were influenced by jazz as well, and they couldn’t get jazz on the radio anymore because radio stations weren’t playing it, they were playing Patti Page and Guy Mitchell, you know, there was that soft period of pop music in the early 50’s where you could only dance to it if you were waltzing, and these young people wanted to do more than that. They’d been influenced by the Americans during the war, you know, learning how to dance jitterbug and jive, and they wanted to do that.”

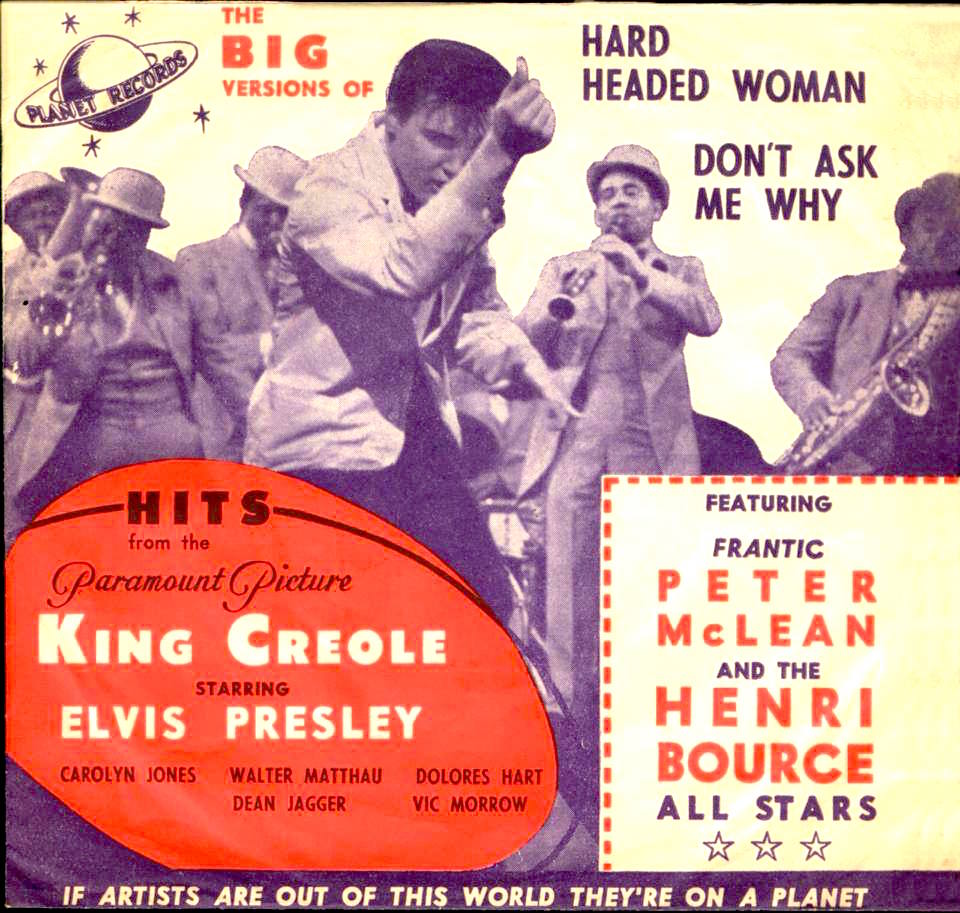

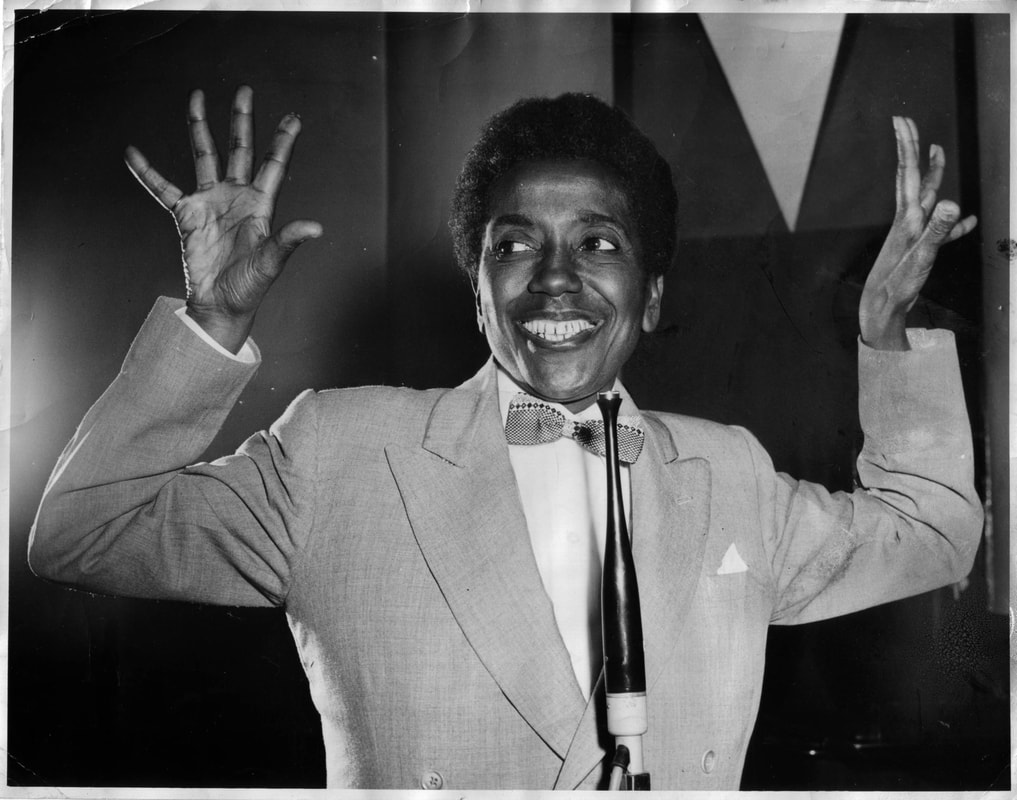

A ‘Bodgie Jamboree’ that Bill McColl promoted at Sydney Town Hall in April, 1951, featured Bob Gibson, Bobby Limb, Edwin Duff and Charlie ‘Parker’ Munro. Even Bobby Limb cut a version of “Flying Saucer.” John Greenan: “You’d go to a dance, you had five saxes, five trumpets and four trombones and they were playing big band jazz but it had a similar beat to rock, you know, rock wasn’t that far away from it, just simpler. So bodgie then melted into the rock scene…” Says Alan Dale, a young band singer who would switch over to rock’n’roll about the same time as his friend Johnny O’Keefe: “Les Welch had a record out called “Saturday Night Fish Fry,” which was actually a twelve bar blues song, which was a forerunner of rock’n’roll. You could play that now and say it was a rock’n’roll record, it was blues and let’s face it, that’s what rock’n’roll was.” Wally Norman: “When rock’n’roll hit, of course not many people realised it is based mainly on old blues chords. The first rock’n’roll musicians were people who’d heard the jazz and blues and R&B and they would improvise on these chords. The kids of the time – I’m talking about the early 50s now – they appreciated the strong beat in rock’n’roll, which is a similar type of beat to the old traditional jazz. Dixieland jazz had a very, very strong beat.” If 1955 opened with a Lee Gordon-promoted Australian tour by Frank Sinatra, the biggest singing star in the known universe, by the end of the year Sinatra was old hat, and the worldwide musical landscape irrevocably different. In July, premiere Australian screenings of ‘juvenile delinquent movie’ Blackboard Jungle, which sported Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” as its theme song, caused near riots. The song itself had been out in the US for over a year on Decca Records, but EMI Australia, which held the local license option, had passed on it. After Les Welch jumped, Festival released it as one of its first singles in the new 7” 45rpm format. The 10” 78 single-play would soon be dead. The following month, around the same time promoter Bill MacColl put on a rock’n’roll show at Leichardt Stadium featuring Welch, Monte Richardson, the Four Brothers and Norm Erskine, the Sun-Herald in Sydney ran a story headlined “Rock and roll is here now.” The story quoted Welch, who asserted that rock’n’roll is “the purest form of jazz – the real jazz. Here in Australia it will be the young person’s music. It is something new to them. Actually it is nothing new – we have been recording and playing rock and roll for the past twelve years. For me, it is the only music.” The newly-arrived multinationals and even EMI dabbled in rock’n’roll, but soon got discouraged. ARC had by now been bought out by US CBS, but its new imprint Coronet wouldn’t touch rock’n’roll. Les Welch’s glory days were numbered too. Festival had taken on a new Sales Manager by the name of Ken Taylor, and he would soon replace Welch as the label’s A&R Manager. Dutch major Philips, under the musical direction of Englishman Gaby Rogers, started recording local, mainly country artists in 1954, and it was probably the first to try and cash in on rock’n’roll with a waxing by Richard Gray. Backed by Rogers’ band and with vocal support by the Four Brothers, Gray was a ballad singer unsuited to Chuck Berry and/or Fats Domino, and even Tempo magazine could see, “as both sides are slanted towards R&B style, the orchestra lacks the exuberance and impetus that this type of music needs to be convincing.” Much more convincing was a single called “End of the Affair” by Nellie Small, and even moreso, Vic Sabrino’s version of “Rock Around the Clock.” Nellie Small is another lost curio. If Australia’s grand dame of music was Nellie Melba, if Edwin Duff was its great white Queen, this other Nellie was Duff’s alter-ego, a sort of cross-dressing black king. Small was indeed pint-sized, an Australian-born Jamaican whose schtick was that she dressed and generally presented as a man, off- as well as on-stage. Small sang with trad jazz outfits like the Port Jackson Jazz Band and Graeme Bell’s band and she boasted a reasonable feeling for the blues. Ken Taylor, before he’d joined Festival and was still working freelance, could see some potential. He co-wrote “End of the Affair” with Red Perksey and produced the session with Trevor Jones’s orchestra. Released on the Mercury label, it became, at least according to Taylor in his memoir Rock Generation, “a minor rhythm-and-blues hit with a heavy rock’n’roll accent.” Vic Sabrino is yet another elusive figure. ‘Sabrino’ was merely a stage name for George Assang, a Torres Straight Islander who was regarded by many as the only man in Australia in the 50s who could really sing the blues, which he did with bands like Graeme Bell’s. “He was the only guy I knew who could silence a Sydney pub,” says his then-agent John Singer. “The only other guy was Harry Belafonte.” Assang was taken under the wing of Red Perksey, whose grooming included changing his name, presumably because it was felt a mixed-blood Asian-blackfella had less chance of making it than some would-be Italian stallion a la Dean Martin. Perksey’s arrangement of Sabrino’s debut version of “Rock Around the Clock” is better than stiff, and even features a fairly honking sax solo. But it’s Sabrino’s deeply-hued vocalese that lifts the track. Probably the best of all these 1955 recordings though were the four sides Les Welch cut with visiting American singer Mabel Scott, even if, for that reason, they might not strictly-speaking qualify as Australian. It was, in fact, a sort of full circle for Welch, since his 1949 debut was a Mabel Scott cover. The two Festival singles that resulted from his September ’55 session with the lady herself were almost as if his swan song. Welch, ever the opportunist, was happy to merge in with the rising tide of rock’n’roll, and when he appeared at Bill MacColl’s Leichardt gig, the five numbers he performed were “Rock Around the Clock,” “Mabel’s Blues,” “Elevator Boogie Blues,” “Rain or Shine” and “Bucket’s Got a Hole in It.” When Mabel Scott toured the country the following month as part of the Harlem Blackbirds all-Negro revue, Welch went down to the Palladium Theatre and there they recorded four sides: “I Wanna Be Loved, Loved, Loved,” “Just the Way You Are,” “Boogie Woogie Santa Claus” and “Mabel’s Blues.” In a way these tracks were a throwback to unabashed pre-rock’n’roll R&B, and as such, with great performances by both band and vocalist, they are lost treasures – raucous, joyful and reverberant. “Boogie Woogie Santa Claus” still rates as one of the best Christmas songs. But for Les Welch, these sides were the beginning of the end, and rock’n’roll in Australia, which Welch had done so much to pave the way for, would grow on without him. By 1956, with Elvis having hit now too, the rush was really on. Vic Sabrino released a second single; Frankie Davidson and the Schneider Sisters entered the fray with creditable efforts; while other names like Frank Crisarfi, Ray Melton and Peter McLean, even Jimmy Little and Ned Kelly, all pushed the definitions. Rock’n’roll was already so entrenched, despite continuing predictions of its imminent demise, that it was already being co-opted. No less than three local versions of the Patti Page hit “Rock’n’Roll Waltz” were released in ’56: one for Colombia/EMI by singer Darryl Stewart with Bob Gibson’s band; one for Diaphon by jazz veteran George Trevare; and one, of course, by Les Welch, somewhat fittingly his last release for Festival. Tempo said of the Colombia disc – and this was obviously a not untypical problem - “Darryl sings the number as a ballad and neglects the essentially rhythmical aspect of the tune.” Vic Sabrino’s second Pacific release was probably better than his first, he and Perksey getting more into the rock groove. But an Elvis twofer – “Blue Suede Shoes/Heartbreak Hotel” – was a bit too obvious for real rock’n’roll, and Sabrino a bit too smooth. Frank Crisarfi, Ray Melton and Peter McLean were very much the proverbial flashes in the pan, with Crisarfi’s process recording of “All Shook Up” and Melton’s “Rock Right” (Prestophone) mere diversions, though McLean’s Planet Records single “Hard-Headed Woman” is lent some credibility by the backing of jazz sax-man Henri Bource, who would go on to lead pioneering Melbourne instrumental combo the Thunderbirds and also produce what seems to be Australia’s first rock’n’roll album, 1958’s All-Stars’ Rock’n’Roll Party, on Planet. Aboriginal country crooner Jimmy Little gets a mention because his earliest releases for EMI label Regal-Zonophone, sides like “Sweet Mama,” had very much a rockabilly lilt to them. Similarly, Ned Kelly was a would-be rockabilly rebel, although he remains almost a phantom compared to Jimmy Little, who today is the grand patriarch of black Australian music. Kelly was much more an American-style honky tonk singer than a bush ballader, and it was this plus his volatility that seems to have seen him almost run out of the business. Arriving in Sydney from Parkes, the former gun shearer and Hank Williams acolyte released four sides through Prestophone in ’56, “I Can’t Help It/Everybody’s Lonesome,” and “They’ll Never Take Her Love From Me/Moanin’ the Blues.” This sort hillbilly boogie was but one step short of rock’n’roll. The record that really saw country take the obvious leap though was the Schneider Sisters’ Magnasound label EP Rock’n’Roll with the Schneider Sisters. Mary and Rita Schneider were a hillbilly duo that specialised in comedy and yodelling, who’d even had an original number called “Boogie Woogie Train Blues” during the war years, but even for all the calculation of the EP, the fact is that it has an irresistibly exuberant rockabilly feel. “Country music with a backbeat,” as Col Joye defines rockabilly, “became rock’n’roll, which was an extension of jive, which was an extension of the Black Bottom, all to the way back to the Charleston and so forth.” “Rock and roll started in ’56,” says Mary Schnieder. “And, somebody I knew, we knew a lot of people in radio, and this DJ, said to me, It’ll never last, never. Give it six months. I said, I’ll have a bet with you it’ll last. I won the bet of course. Because it never did finish, did it? “We made an early, EP? Wasn’t it an EP?" |

|

Rita: “It was. It was an EP …”

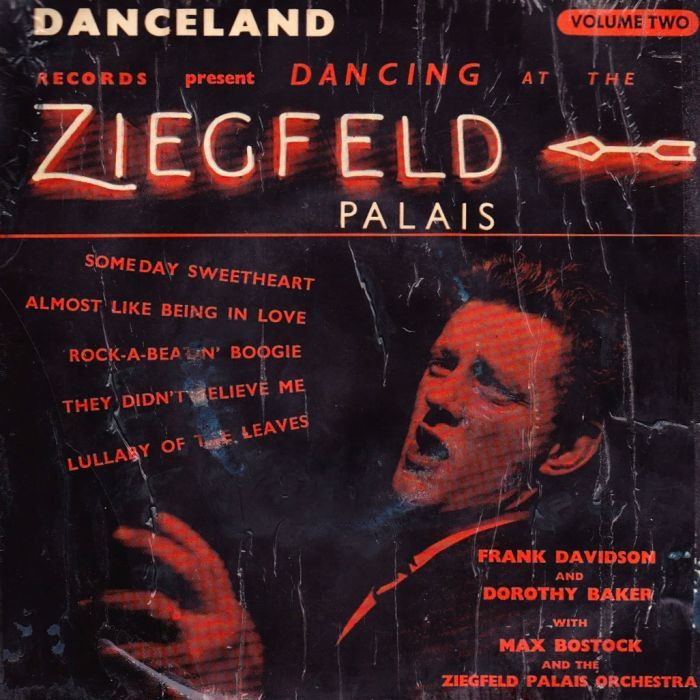

Mary: “On MagnaSound label. In Melbourne.” Rita: “In 1956.” Mary: “It was a little EP with four tracks. We did that with Lee Gallagher’s band in a, in a hall too … And they put the microphone in the, in the toilet to get some nice echo effects. We had three songs, ready. The night before, we thought, Oh, what are we going to do? we need four. So we wrote a song in about a half an hour called “Washboard Rock’n’Roll.” I think it was the second rock’n’roll record that was ever made in Australia. It was the second wasn’t it?” Rita: “I think it was the second, yep.” Okay then. The other 1956 recording that’s at least as good as Vic Sabrino is Frankie Davidson’s version of Freddie Bell and the Bellboys’ “Rock A-Beatin’ Boogie.” Davidson, like Vic Sabrino or Edwin Duff or Alan Dale, was band singer, whose regular gig in Melbourne was at the Ziegfield Palais, where the house band was led by Max Bostock. In early ’56, he went into the studio with Bostock: “They put down three tracks,” he recalled, “and they said, Why don’t we try a rock’n’roll track? and we weren’t allowed to do “Rock Around the Clock,” so we got a copy of “Rock A-Beatin’ Boogie.” “ The track was included on an EP on the Danceland label called Dancing at the Ziegfield Palais, Volume Two. “It wasn’t done with a rock and roll band, it was done with a ballroom orchestra as such, but it still had the rock beat.” This Davidson followed up later in the year with a version of Bill Haley’s “See You Later, Alligator,” which was included on the Danceland EP Rock and Roll with Frank Davidson; Bostock’s band was here billed as the Rockets. The other tracks on the 7” vinyl are more skiffle than rock’n’roll, songs like “Rock Island Line,” “Camptown Races” and “Frankie and Johnnie,” with all arrangements credited to Bostock/Davidson. “I don’t think we’d sort of reached the stage of discovering ourselves at that time,” Davidson said. “It all happened pretty quick, you know. You’ve gone from ballroom dancing in the mid 50’s and suddenly you’re into rock’n’roll… If the fathers had grown up blowing saxophones and trombones and then suddenly you cut to piano-bass-drums-guitar – a guitar out there playing lead was the basis of rock’n’roll, you know – it takes a while for that stuff to evolve, to get bands together, change music patterns. Old habits die hard, you know.” By 1957, the dogfight was on to find or create Australia’s first rock star. |

|

Les Welch, nearing the end of his recording career, returned to ARC to cut a few sides for the Prestige label, but there was something ignominious about an Elvis twofer like “Hound Dog/Don’t Be Cruel” (a cover of Bill Dogget’s US instrumental hit “Honky Tonk” was better), and before long, with TV now in the offing, Welch would join Channel 7 as its Musical Director, not to release another record till the early 70s.

Ken Taylor lured Vic Sabrino to Festival before he was virtually blackmailed into giving Johnny O’Keefe a contract, and after that, nothing was the same again. Sabrino cut a number of singles for Festival including “Fraulein/Hitch-Hiking Heart,” “Long, Long Lane/Painted Doll,” “End of the Affair/Drifting By” and “Time for Parting/Merry Go Round.” Taylor was trying to fuse rock and pop on the basis of original Australian songwriting. Australia might have started to learn how to make rock’n’roll records, but songwriting, at least outside country music, was still largely unchartered waters. Taylor tried Sabrino on his own “End of the Affair,” which had already stiffed for Nellie Small, and he wrote another song, “Hitch-Hiking Heart,” that he tried a couple of artists on. He got in bandleader Gus Merzi to back Sabrino on “HHH.” Sabrino is more comfortable with something softer like this and the recording can claim the distinction of being the first Australian composition to be released in the US, as it was on Decca. |

|

Taylor tried Ned Kelly on “Hitch-Hiking Heart” too. Festival had leased six sides off Ned, versions of Hank Williams tunes like “Lost Highway,” “Mansion on the Hill” and “Move It On Over,” and they were very good. Taylor wanted Ned to go rock’n’roll, and so he tried him on a single on Festival, which put “HHH” on one side and on the other, “Painted Doll,” a song Ned himself co-wrote with George Dasey. “Painted Doll” was a rockaballad that wasn’t half bad; backed his own band – neither the Glenrowan Boys or Rock Gang or Kelly Gang but the Western Five – Ned sounded good. But even if the leap from Hank Williams to rockabilly wasn’t great, Ned was a prickly character who much valued his integrity, and he was reluctant. He returned to cutting more hardcore country sides before mysteriously disappearing.

Taylor in turn tried Vic Sabrino on “Painted Doll,” and hiring in the newest hot bandleader around town, American sax-man Dave Owens, he got a result that sounds cheesy next to Kelly’s. It wasn’t a hit and Sabrino went on to cut eight skiffle sides with Graeme Bell for Colombia, which were hits. Skiffle followed calypso as an apparent challenger to rock’n’roll; the skiffle boom in the UK would produce the Beatles no less. It was easy for Graeme Bell, and Vic Sabrino, to understand, because basically it was close to a trad jazz repertoire but with acoustic guitar prominent. Sabrino sang well songs like “Freight Train,” “Sweet Georgia Brown,” “John Henry,” “Don’t You Rock Me, Daddy-O,” “Gamblin’ Man” and “Gospel Train.” (The trad. jazz feed into Australian rock is significant, going from directly spawning the Loved Ones, who began life as the Red Onions Jazz Band, and extending so far as the Ted Mulry Gang going to #3 with “Darktown Strutters Ball” as late as 1976.) After that, Sabrino returned to his real name and reunited with his brother Ken to form the Assang Brothers, who in 1965 cut an album of gospel harmonising for Philips called Just a Closer Walk with Thee, before becoming an actor and marrying Rowena Wallace. The lasting breakthrough of 1957 though belonged to Johnny O’Keefe. When in October Bill McColl staged a show at Manly called Jazzorama, featuring O’Keefe, Les Welch, Col Joye and trad jazz outfit the Ray Price Trio, it marked a changing of the guard. O’Keefe would lead the way for all the other first-generation Australian rockers, including Col Joye, to follow. Like Vic Sabrino or Alan Dale or Edwin Duff, Johnny O’Keefe started out as a band singer, essentially a Johnnie Ray impersonator, in which form he was making such headway that in November, 1955, he played the support spot on an Australian tour by Mel Torme. But even as he was taken under the wing of Gus Merzi, he was already torn, because by then, like every other budding young singing star including Alan Dale, he’d heard Bill Haley and been blown away. During 1956, O’Keefe wrestled with trying to move in this new direction, shake off the Johnnie Ray songs. In November ‘56, billed as “Australia’s Gentleman of Jazz,” he headlined a show at Brisbane Town Hall backed by a local band called the Rock’n’Roll Rockets. His friend Alan Dale was in the same boat. “I could do a fair impression of Bill Haley,” Dale remembers, “but couldn’t come up with offbeat musical backing, as most pubs supplied only a pianist. I had to build a band exactly the same as Haley’s Comets.” So did JOK – and this he did when he hooked up with Dave Owens and formed the Dee Jays. It proved to be the key: O’Keefe was the first with a band. If you wanna rock, you gotta get with the beat. Dave Owens was already assembling his own jazz band with an R&B edge in Sydney before O’Keefe came along. Owens had arrived in Sydney from the US after meeting Jack Brokensha and his Australian Jazz Quintet in Detroit (the American tour that effectively killed Edwin Duff’s career). As the Blue Boys, Owens did some sessions with Vic Sabrino. But Sabrino was a shrinking violet next to O’Keefe. Neither Alan Dale’s Houserockers or Ricky Miller’s Brothers were any match for JOK with the Dee Jays. When Lee Gordon toured Bill Haley in January 1957, O’Keefe managed to get backstage at the Sydney Stadium and even blagged a song off Haley. It was this song, “Hit the Wrong Note, Billy Goat,” that sold O’Keefe to Festival and would become his first single. In February, after debuting at the Trocadero, JOK and the Dee Jays launched their own regular dance at Stone’s in Coogee. When JOK went back to Brisbane Town Hall with the band, he was now billed as “Australia’s King of Rock’n’Roll.” The Dee Jays opened the set with “Blues by Five,” by Miles Davis. Says John Greenan, who joined from the Brothers: “Dave was the brains behind the band because he knew black music, he was a great jazz soloist and I was an up and coming jazz soloist. Dave could really get in and play the R&B-rock’n’roll sound that was really convincing, and we hadn’t had that here. Johnny really took to that; up till then he’d been doing Johnnie Ray impersonations. He was sort of into jazz but he knew rock was going to do it, and so Dave was a great help to him. There was this marriage of convenience.” Alan Dale: “Actually, back in those days, most of the people you used came out of the jazz field. My first guitar player Neville Chamberlain was a great jazz player, but he adapted because he knew that there was more money in rock’n’roll.” In June ’57, O’Keefe and the Dee Jays went into the Prestophone studios with producer Robert Iredale and cut “Billy Goat,” with a Dave Owens composition (“The Chicken Song”) for the B-Side. It wasn’t great, or a hit, but still O’Keefe, with his usual larrikin front, managed to convince Lee Gordon to put him on the bottom of the bill of October’s Little Richard tour. John Greenan: “Little Richard came and we watched every show and that really affected us a lot. [It was Little Richard with his full Upsetters band, in his full glory, at least up until he renounced rock’n’roll for the Lord when Sputnik passed over Melbourne: It would have made an impact!] That was the first Lee Gordon Big Show tour we did and that’s when I came into the band, just before that. We had two tenor saxes and the rhythm section so it suited John, suited his voice, his approach, and from that he was flavoured.” O’Keefe’s second single, “Am I Blue?/Love Letters in the Sand,” was a stiff he quickly disowned. The kids didn’t want to hear ballads, O’Keefe knew that, they wanted to rock, R-O-C-K!! The search was on for the Song. Greenan: “One night we played a dance in Newtown, a place called Mawson’s, we were playing upstairs, not a big hall and it had a balcony which overlooked the square where all the trams used to run in Newtown. There was an Italian wedding going on downstairs. Half way through the night, all of a sudden, our dance clears out, the kids are all gone, and I’m saying, What’s wrong? our music’s not that bad! So we went to the balcony and looked out and there’s this huge brawl. Naval Police, Civil Police and they’re all biffing up and we found out what went on: Somebody upset one of the Italian people at the wedding and then the kids all got involved and there was this massive brawl. They cleaned it up. The dance ended, we didn’t finish it, and Dave and I went back to listen to some Miles Davis and we had a couple of bourbon and Cokes to sort ourselves out and Dave was very sardonic, he had this sense of humour, and he said, Hey man, what are we doing with all these kids? you know, we’re corrupting them! So after a couple of more bourbon and Cokes and a bit more Miles Davis and John Coltrane, we started writing these words down. It was as simple as that. It was quick. We both contributed and had all this stuff in another two hours, about 4 o’clock in the morning. We had a recording session I think two days later with Johnny at Festival down at Pyrmont. We took it in and said, Hey John, we wrote these words the other night, and John said, Gee I like this Wild One stuff, you know – what’s the chord progression? I don’t think Dave and I had even discussed it. Oh, it’s 12 bar blues, we said. So we there and then did a head arrangement. We used to do a lot of head arrangements on the spot. O’Keefe loved it and we recorded it on the spot. Festival released it and it was his first hit.” |

|

“The Wild One” wasn’t actually released as a single, but rather as one of four tracks on the EP Shakin’ at the Stadium (studio recordings with applause grafted on so as to sound live) – though it soon stood out, not least of all as an original composition alongside covers “Ain’t That a Shame,” “Silhouettes” and “Little Bitty Pretty One”. The songwriting credit on the record's label went to O'Keefe/Greenan/Owens and Tony Withers. Withers was a Sydney DJ and his name appeared for the same reason Allan Freed sometimes took co-composition credits on American rock'n'roll records - as a way of ensuring (in effect, buying) airplay. (And just as Freed's name was eventually removed from some of the songs he was supposed to have co-written, Withers' name was removed from the "Wild One" credit.) The track was given boost when O’Keefe appeared on Lee Gordon’s Buddy Holly/Jerry Lee Lewis Big Show tour of January ’58, and by March it had hit a high of #26 on the newly-convened Australian charts.

|

|

O’Keefe was now poised to become a star of a magnitude and type never before seen in Australia. He would eventually die in 1978, a year after Elvis. Nothing he did, or that or any Australian rocker of the first wave did, has lasted or travelled like “The Wild One.”

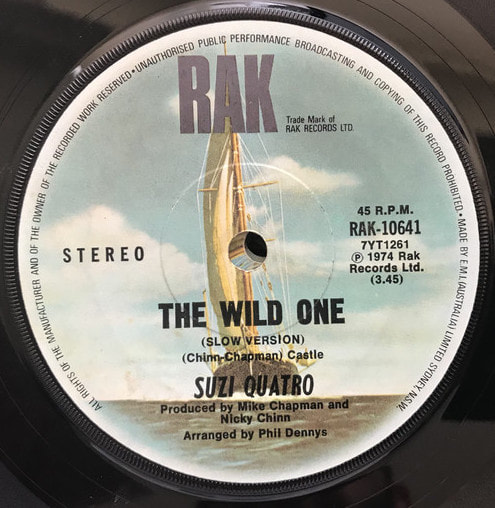

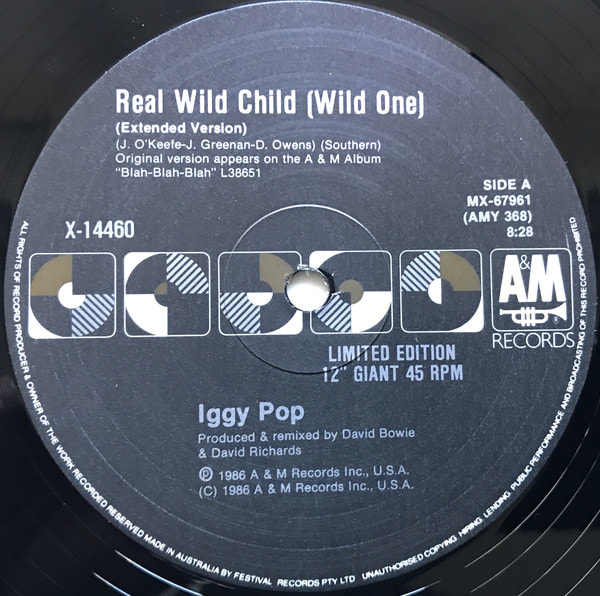

Both Buddy Holly and Jerry Lee Lewis recorded versions of the song almost immediately upon their return to the US in February ’58, although both would trail O’Keefe’s own US release of it, on Brunswick in May, ’58. The song was retitled “Real Wild Child” to avoid confusion with the Marlon Brando movie. It wasn’t a hit for anyone. In 1974, Suzi Quatro included a version of the song on her second album Quatro, but outrageously the songwriting credit was taken by her Chinnichap production team at RAK Records, one half of which, Mike Chapman, would have been very familiar with the song since he was Australian; it's hard to imagine this scam hasn't been righted by now. Either way the song wouldn’t die, and it became a signature and a standard. In 1987, it was about the only real hit single Iggy Pop’s ever had; it probably also fuelled Johnny O’Keefe’s fatal attraction to America, which almost destroyed him. |

|

Before 1958 was out, Dave Owens would leave the Dee Jays, over money. But the band’s name would never be synonymous with anything but raw, raving R&B-based rock’n’roll. Owens was replaced by Bob Bertles, a be-bopper and founding member of Johnny Rebb’s Rebels, who appealed to O’Keefe because he played baritone as well as tenor sax. Owens returned to the US.

When Bill McColl put on a ‘Rock’n’Roll Ball’ at Sydney Town Hall in December ’57, its bill reflected a new order: JOK, Col Joye and Alan Dale. O’Keefe kicked the door down, and in his wake followed Col Joye and all the others Ken Taylor signed to Festival. All the other record companies, including EMI, were left eating Festival’s dust, at least until the Beatles rewrote the rules again in the mid-60s. EMI inexplicably let Johnny Rebb go after one single – the classic original, “Rebel Rock” – and he went on to significant success (if no more great records) on Lee Gordon’s boutique imprint at Festival, Leedon Records. Col Joye didn’t hit till ’59 either, with “Bye Bye Baby,” written by local DJ John Burles. Digby Richards made sense to Ken Taylor because he echoed Col Joye: good-looking, clean-cut and with a gentle, soft rockabilly sound. His first single echoed the classic Les Welch approach: a cover (“Kansas City”) on the A-Side, an original rockaballad (“I Wanna Love You”) on the flip. He would go on to make some great records, but not till the 70s, and as an outlaw singer-songwriter. Col Joye would eventually return to country too. After O’Keefe, early Australian rock’n’roll tended to be much more Nashville than New Orleans. Joye: “We sang all the songs that were popular at the time. They may be by Nat King Cole or Frankie Lane or those. When Johnnie Ray came out, he was different. And then Elvis Presley come out, he was different again, Bill Haley, but basically, country artists did the breakthrough: the Conway Twittys, the Jerry Lee Lewises, Elvis Presleys, the Bill Haleys – they were all country singers. “And so when that came out, me being a cowboy follower, hillbilly follower, it was a normal extension for me to go across into the field of Haley and Presley. And we all tried to emulate Presley. Everybody that I’ve spoken to throughout the years, Johnny Cash, Cliff Richard, Roy Orbison, we all tried to emulate Presley.” But jazz continued to enrich emerging Australian rock’n’roll: Pianist Mike Nock would later join the Dee Jays; and John Sangster, Graeme Lyall and Stewie Spears all played rock in Melbourne; drummer Stewie Spears and Bob Bertles would ultimately unite, in fact, to make Max Merritt’s late 60s’ Meteors one the great white soul bands. As for Alan Dale, he became the ultimate bridesmaid. After getting the brush-off from Ken Taylor, Dale was finally called in, too late, by EMI. EMI let him debut, in ’59, with an original composition, “Kangaroo Hop,” but Australia would have to wait a few years yet for its own dance craze in the Stomp. For his second single Dale covered two titles from the Chess Records’ catalogue that EMI itself refused to release in Australia – Chuck Berry’s “Back in the USA,” and Bo Diddley’s “Crackin’ Up” – but the result was a bit like the horse had bolted. The irony was that while Berry may have written “Back in the USA” as a love song to his country, he did so when he was on tour in Australia (in February ’59) and desperately homesick because he hated it here, hated the racism and the lack of convenience and flash. Dale’s version of the song, either way, was pallid, and EMI let him go. Now, even Slim Dusty was cutting “Pub Rock”! |

|

Thanks for their assistance in the preparation of this article to Peter Doyle, Peter Cox (Powerhouse Museum), Brett Assang and Nick Weare (ScreenSound), and for interviews to John Greenan, Bill Gates, Wally Norman, John Singer, the Schneider Sisters, Alan Dale and Frankie Davidson.

|