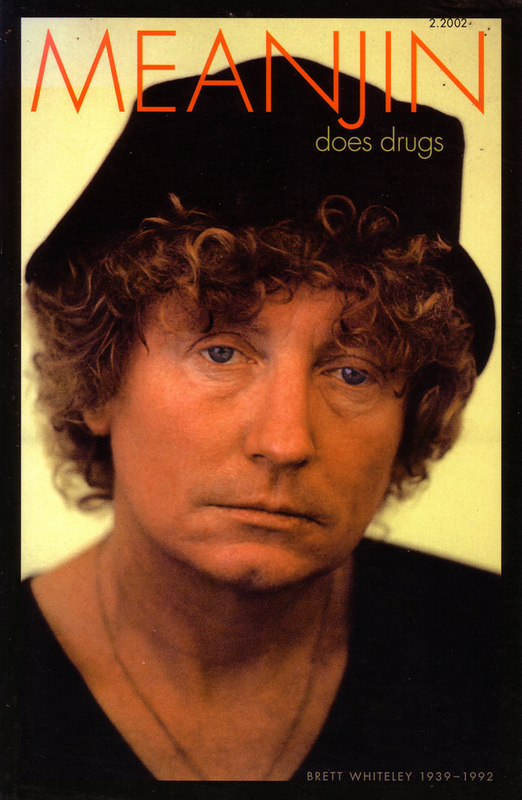

CO-DEPENDENT: DRUGS, (OZ) MUSIC & ME, A POTTED HISTORY

Originally published in Meanjin, 2002

|

I can still remember my first joint. All the usual jibes notwithstanding (memory loss, not inhaling, whatever), I remember it vividly: It was at the University of Queensland, around 1972 or ’3, a Student Union gig at the Refec. with MacKenzie Theory playing. Now of course anyone else who remembers MacKenzie Theory might laugh, Well, you’d have needed a joint! - and that alone illustrates the almost inextricable link between drugs and music - but the seemingly free-form instrumental wailing of this Australia Council-sponsored, electric viola-led space-rock quartet (a sort of precursor to today’s Dirty 3) was in fact grounded in a serious sense of purpose, not to mention a deal of discipline too (as is the case, inevitably, with most ‘seemingly free-form’ music).

|

|