ROCK INK

|

The pages that follow here add up to a chronological bibliography of books about rock’n’roll and popular (music) culture published between the mid-50s and mid-70s. It came about because, as I often find, I was doing some research and I needed a reference-source something like this but no such thing seemed to exist – and so in the true spirit of punk in which I was inculcated, I did it myself! I needed to better understand the way the literature of rock, in book form, developed in those early days from its beginnings; I needed to be able to see, at a virtual glance, a clear and relatively comprehensive overview of that development, stacking all the hits we know so well against the many more (and more unfamiliar) misses, so as to place them all within the broadest context….

I am posting it up like this, as a work in progress, because I can’t see it getting published anywhere else, and I think it can be useful. All I’d ask is, if you do find it useful and you apply it somehow, please at least give that attribution… |

|

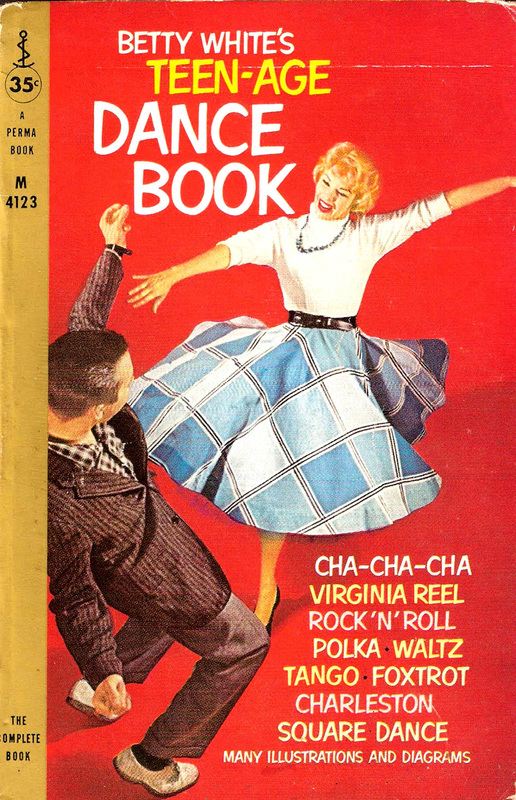

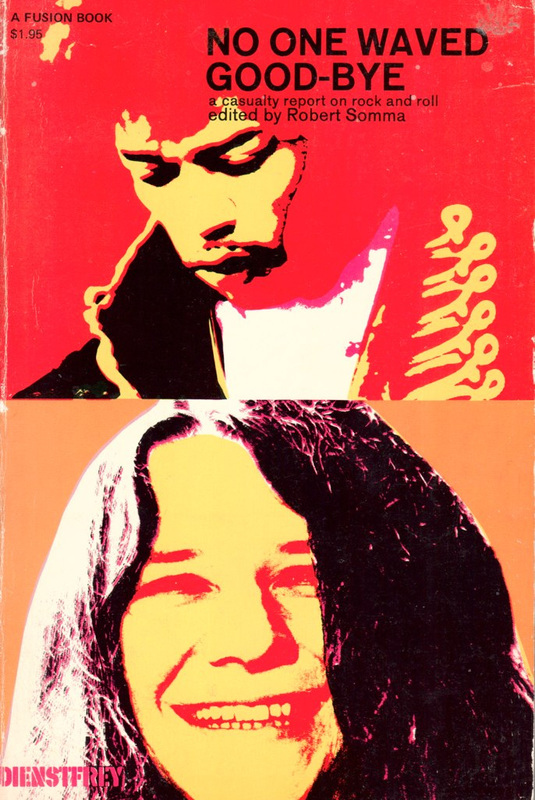

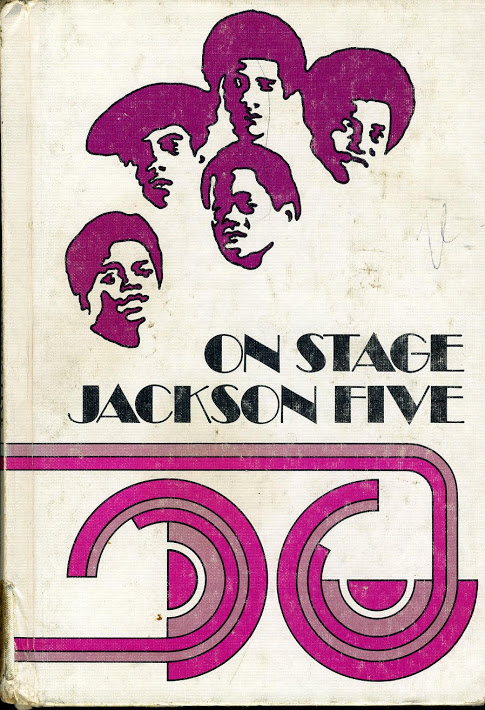

Naturally I can’t claim that these listings are totally comprehensive, but they're more comprehensive, I’m fairly confident, than any other such similar source I’m aware of. They're not airtight because, well, what can ever be? I think it’s a good rough guide, and it’s not meant to be anything more. But by drawing on the bibliographies of some of the earliest publications themselves, plus also bookseller and library catalogues and fansites, and importantly forty years of personal experience building up my own library, I’ve been able, I think, to fill the gaps. (Two books themselves, Ed Hanel's Essential Guide to Rock Books [Omnibus, 1983] and Paul Taylor's Popular Music since 1955: A Critical Guide to the Literature [Mansell, 1985], were both useful but also both full of holes.) The listing’s logic should become fairly self-evident as it unfolds. Only the timeframe might require some explanation. It ends in 1976 because, well, you can see it in the entries, the mid-70s was a real dip after the explosion of the late 60s/early 70s, and in so many ways that dip, which was in terms of both quantity and quality of writing, marked the end of a cycle, before a new cycle started in the form of punk, which is where I came in myself and is a whole other story I didn’t want to get into here. There is in the short ‘Precursors’ section in Part 1 a few books about jazz and movies, and though those subjects don’t follow through, their early literature was part of what inspired rock writing. The follow-through is in the literature of folk and blues, because those genres and their literatures were intertwined with the development of rock and its literature. If this listing is all about plotting out a basic bookshelf of rock, there were many books about folk and blues that no self-respecting streetcorner scholar could have gone without. Obviously so much of the action in music writing has always taken place in magazines, not books. That this listing is devoid of some of the most now-fabled writers of the period like, say, Al Aronowitz, Paul Nelson, Lester Bangs and Nick Kent, is a good indication of the fact: they didn’t publish in book form until much later, if at all. But it is books that are the subject of these pages, and the way the publishing business responded to the youthquake of the period and its clear potential to make a lot of money. The listings take in fiction and broader non-fiction (from the sensationalist sociology of 50s’-style juvenile delinquency to the polemics and sensationalist sociology of the 60s’ counter-culture), as well as the standard run of biographies, general histories, genre histories, prosopographies, regional histories, encyclopedias, photography and art books and collections of lyrics and poetry. Writing about pop music in a way that took the first tentative steps beyond fan magazine fodder began in the UK at the end of the 50s. Al Aronowitz may have always claimed he was the First, but before his admittedly groundbreaking rock journalism started to appear in American newspapers and magazines, there was a clutch of writers in the UK, like Colin McInnes, Royston Ellis and the expatriate American Charles Hamblett, who prefigured rock criticism. From the inception of the underground press in the late 60s, out of it and pushing into the 70s, the iconic names of early rock writing emerged and started to publish books, among them Britons like Nik Cohn, Charlie Gillett and Dave Laing and Americans like Griel Marcus, Robert Christgau, Richard Goldstein, Albert Goldman, R. Meltzer, Peter Guralnik and others; even Australians too, like Lillian Roxon, Ritchie Yorke and Craig McGregor. But for every one of these legends there are many other footsoldiers who toiled in the trenches beyond the shooting-stardom of, say, a single one-off book – writers like David Dachs, Arnold Shaw, Anthony Scudato, Jonathan Eisen, Richard Robinson, Jerry Hopkins, David Dalton, Michael Lydon, Tony Palmer, J.Marks, Tony Jasper and Mike Jahn all published multiple titles which in some cases even rivaled the work of their better-known bretheren (and indeed, it was a male-dominated field) and in other cases trailed it ignominiously. Peter Guralnik is rightly celebrated, for example, for his first book, 1972’s Feel Like Goin’ Home, but as the listing reveals, it wasn’t without its antecedents, not least of all James Rooney's Bossmen, a sort of diptych that innovated the juxtaposition of a black star and a white star, and in the work of Michael Lydon generally. It’s perhaps not so surprising that sensationalist-sociological books about the counter culture dropped off in the early 70s because by then the Dream, as John Lennon once put it, was Over. What is surprising is that there wasn’t a glut of books about gender-bender glam rock that came along to fill that void. But perhaps that’s why this timeline finds a resolution in the place it does, and part of why punk became so necessary too (and conspicuously, as soon as punk reared its controversial head, a literature exploded around it as well) – because by the mid-70s, the literature, like the music itself, had become stale and tame, all West Coast soft rock and Rolling Stone fodder. The next chapter, with the rise of punk/new wave, became a whole different thing again – which due to personal overexposure, I'll leave to someone else to account for... |