VINYL AGE

|

This initially very extended article was first published, in two parts, in the Thesis Eleven journal in 2012, with the byline shared by myself with Peter Beilharz and Trevor Hogan. This version here returns to my original pre-academicised draft. It was an attempt to achieve a balance between telling the sprawling story of record companies in post-war Australia in the shortest possible length but without compromising any coherence. Obviously it goes without a lot of detail and/or colour, but I think it provides a good concise overview of the big picture. Put it this way: If as a collector and researcher I'd had a document like this a long time ago, it would have saved years of wondering and fruitless cross-checking!

|

|

The history of the Australian record business after WWII, like so much Australian history of this period, is one of lessening British influence, increasing American influence and increasing Australian autonomy.

As late as 1964, Gough Whitlam could still claim Australia was “a captive British market, a subject people.” But even before the war, America was colonising the world, including Australia, via Hollywood movies and Detroit automobiles, and after the war, the rise and rise of American consumer culture furthered the process. Since the 1990s’ digital revolution started eating away firstly and most conspicuously at the recording industry (popular music has always been ahead of even cinema and TV at the cutting juncture of art and technology), the fifty years from 1945-1995 can now more clearly be seen as a golden age, certainly the vinyl age and the age of rock. This new popular music form and youth culture was a consequence of the bigger booms of the period: the sustained post-war economic boom and the baby boom, plus the spread of new technology like vinyl records, transistor radios, record players, TVs, electric musical instruments, magnetic tape recording and via-satellite broadcasting. Rock’n’roll met the social needs of an exploding young generation with money to spend, and its impact was so deep it not only reflected the times but sometimes anticipated and helped shape them as well – all via these millions upon millions of little black plastic platters. Etched with grooves out of which leapt magic, these spinning disks had an almost hypnotic effect on generation after generation of Western and Eastern society. The sales volumes of the record business in Australia grew inexorably up until the 1980s, when they started to plateau out even despite a steadily rising population. This was an indication of rock starting to lose the primacy it had so strongly enjoyed in the 60s and 70s, of its receding social force in the face of an aging population, deregulation, diversification and multi-culturalism among other things. The growth extended from units sold in the early 50s, when the population was barely ten million and post-war shortages still acute, of only a few million per annum, to around 6m pa toward the end of the 50s, after rock’n’roll had hit; to 8m by the early 60s, 20m in 1970, 35m in ’75, to 47m at the start of the 80s. The curve was very steep after the entrenchment of albums in the very late 60s all the way through the 70s. Sales hovered around the 50m mark through the 80s into the 90s, and if they slowly grew to a final modest peak at the turn of the century – around 60m pa after the entrenchment of CDs and growing discounting in the wake of the 1991 Prices Surveillance Authority inquiry – this was just as the young internet was really starting to bite into the way music could be consumed. Since then, volumes have plummeted inexorably. By now, the landscape and ground rules of music culture are totally changed from its classic, late capitalist model of the previous half-century. |

|

The biggest growth area within that overall growth of the vinyl age was in rock albums. Sales of 45rpm singles proportionately declined as rock became an album form after the late 1960s. Even as cassettes actually overtook sales of vinyl in the 80s, those cassettes were still formatted to emulate the LP, with only twenty minutes of music per side of tape even when they could easily hold double that; the LP remained the sonic optimum and form-defining medium. Certainly rock and pop music claimed the lion’s share of all sales during this period, at somewhere between 75-90% of the market. In 1990 when Price Waterhouse reported for ARIA (the Australian Record Industry Association) in its submission to the PSA Inquiry into CD prices and parallel importing (one of the first times, as it happens, that the rock industry or record business was so examined and quantified), a 1989 table has contemporary or pop music (meaning rock, country, soul and MOR) claiming 87.5% of the market, ahead of classical with 4%, jazz 2% and ‘other’ 6.5%, ‘other’ meaning ethnic and/or other uncategorisable genres.

|

|

The lion’s share of all sales could also be claimed by major multi-national record companies. Australia was long dominated by a Big 6, which included our own Festival Records, not least thanks to its bedfellowship with Mushroom, plus Britain’s EMI, America’s CBS, RCA, WEA, and Europe’s PolyGram (originally Philips). This number might also extend to a Big 7, at least up to the 80s, if it includes Melbourne’s Astor Records if a major is defined as distributing its own product as well as manufacturing and marketing it.

At any given time into the 1990s, the Big 6 ARIA-founder labels were shifting up to 80-90% of total local record sales, with the remainder made up by successive waves of independent startups. Labels like Mushroom and Alberts certainly became ersatz majors in terms of repertoire, and a label like Shock grew out of the underground as principally a distributor that would go on to claim a major’s proportion of the market. Local artists, increasingly encouraged by radio, whether public stations like Melbourne’s world-standard 3RRR or commercial airplay quotas, have variously claimed between about 10% and 30% of total sales. The record business was like a food chain crossed with a big game of musical chairs, in which record labels of varying states are eaten up and spat out and shuffled around via territorial copyright deals that figure and reconfigure world-wide networks. This is why it’s sometimes very hard to keep track, historically, of record companies, because bits of them are always coming and going. In Australia, a far-flung colonial outpost, the record business was founded on these sorts of arrangements, and it grew in much the same types of cycles as it did everywhere else, with, on top, multi-national labels and licensing deals accounting for a local order of major labels and, at the bottom, independent labels fostering grass-roots music which then in turn starts climbing the ladder. Or not. |

|

It’s a telling measure of the decimation of the record business the way that those Big 6 or 7 labels have since reconfigured into a veritable end-game landscape. Mushroom was fully bought out by Festival which in turn was bought out by WEA, making for Warner-Festival. CBS was bought out by Sony, RCA was bought out by BMG, and then the two entities merged to form Sony-BMG. EMI stood firm for long time. PolyGram bought out Astor way back in the 70s, which allowed for the hitherto Astor-distributed American major MCA to go out alone even before it took on its new global brand-name Universal; which going from power to power bought up PolyGram and then bought up EMI, and is today is probably the biggest conglomerate dominating the game, in Australia as around the world.

The Australian music industry, by its old definition, still rhapsodises over the 1980s. The biggest of the big, Cold Chisel or INXS – the apogee of beloved pub rock – this was bigger than Australian music had ever been. Cold Chisel could sell nearly a quarter-million per album in Australia alone. And then INXS broke in the US to sell six million copies of 1986’s Kick, and Australia was the flavour of the month, with films like Crocodile Dundee and other bands like Crowded House and Midnight Oil making a big impact in the US, and bands like the Divinyls and the Church having hit singles too. |

|

But even then the seeds of an end were showing. The boom in Australian music was completely in keeping with the blockbuster excess of the greed-is-good decade. The growth of the Australian record business from a worth of $140m in 1980 to $340m in ’89 was not due to a real number of increasing sales, but rather to a) an inflation in the retail prices of records and, b) in the latter years of the decade, the introduction of the CD, whose early sales were propelled by back catalogue, in other words, were being bought as replacement technology for old records. Of course this was a great gravy train for record companies, simply selling all the classic hits all over again.

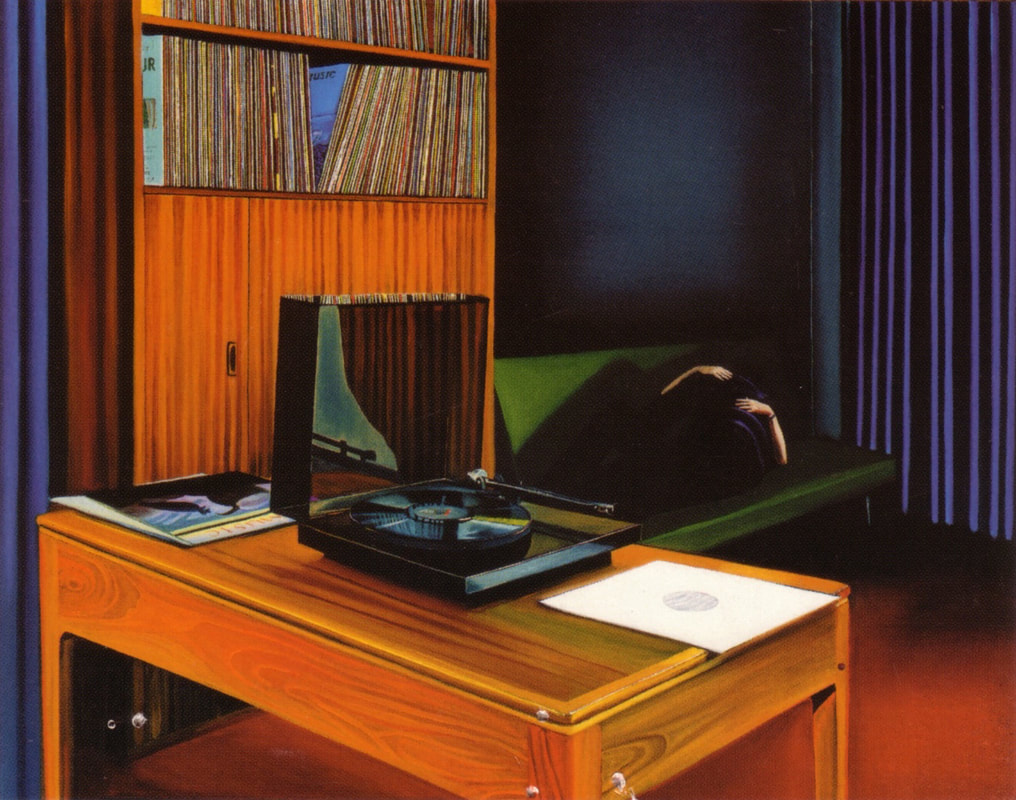

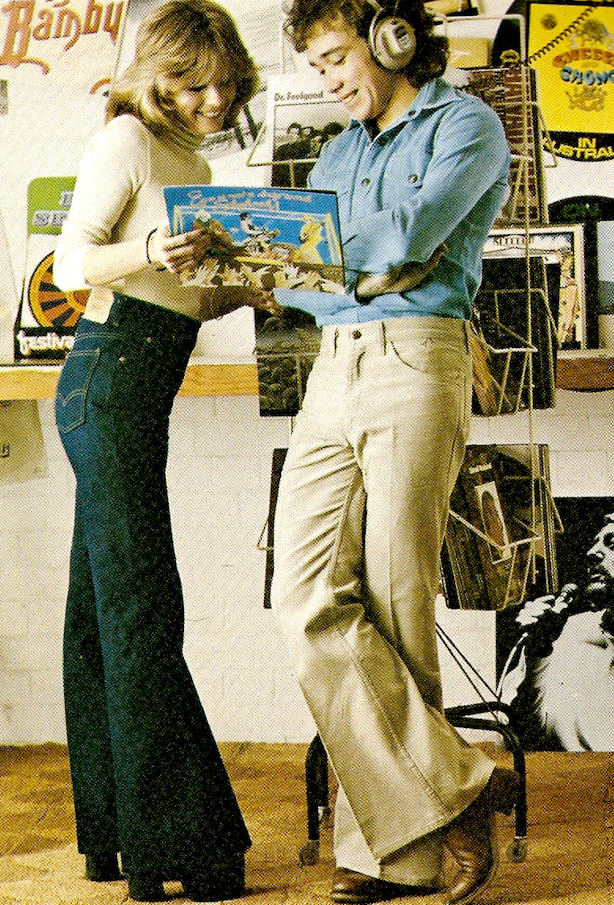

As soon as the mid-90s, at the height of the grunge movement, with the CD already entrenched, the hype was already transparent: Whenever a hot new band like silverchair or You Am I went to the top of the charts, as the old timers liked to cry, they weren’t selling a fraction of what Chisel and the rest of them did in the good old days. And this was before the internet really started sinking its teeth in. The growth of the export value of Australian music runs in delayed parallel. From a worth of a mere $10m pa in the mid-80s, by the early 90s that figure had grown ten-fold, to almost $1b, and by the end of the decade, the turn of the century, it had doubled to over $2b. Where Australian acts in the 60s and 70s had made what seemed like nothing but kamikaze missions overseas, in the 80s and 90s Australian music became merely an accepted part of the international circuit, thanks not only to multi-Platinum stadium rockers like INXS, LRB, AC/DC, Midnight Oil and Crowded House, or even multi-Platinum popsters like Olivia Newton-John, Kylie Minogue and Savage Garden, but also thanks to ‘marquee’ independent acts like Nick Cave, the GoBetweens and the Triffids. Although, since then, export worth too, like everything else, has declined. The story of record business traffic into and out of and within Australia is a confusing web of constantly shifting interconnections that might best introduced with a point-form periodisation that adds up to the 6 Parts of this article to follow: Part 1/ PRE-ROCK: the decade from the end of the war to the mid-50s, during which vinyl, initially the 10” 33rpm LP, starts to supersede shellac 78s, and EMI’s pre-war monopoly is broken by the arrival of Euro major Philips plus local startups like ARC, Festival, Astor, Diaphon, W&G, Spotlight and others. Part 2/ ROCK REVOLUTION: Mid-50s to early 60s; in ’55, rock’n’roll hits via new vinyl 7” 45rpm single, and the global expansion of major American, British and European record companies means a new order of international licensing networks, which brings American majors RCA and CBS direct to Australia. Festival cleans up on local rock while most of the other pioneering pre-rock labels die. Part 3/ A.B. - ‘AFTER THE BEATLES’: Up to the end of the 60s and the entrenchment of the Album as Art Form. Australia’s Beat Boom, dominated by EMI and Festival but also impacted upon by the other majors plus a whole new wave of regional independent labels like Spin, Sunshine, In, Go!! and Clarion. In the late 60s it’s the majors who lead the transition of rock onto the increasingly affordable 12” album format, led by EMI and new local standalone CBS and WEA operations. Festival launches in-house Infinity label to keep up with new major-boutique labels like Harvest and Vertigo. Part 4/ WIDE OPEN: early to late 70s; from Sunbury to Countdown, the rise of rise of album rock, Australian rock and pop, and the entrenchment of Australian power bases. EMI, Festival and other majors still dominant but new independents like Mushroom, Fable, Sparmac, Havoc, Alberts, Wizard, Tempo and M7 realign the balances. Part 5/ CORPORATE ROCK: Late 70s to early 90s, a long period because the cycles now actually slow down or stretch out, as corporatisation codifies and streamlines the processes. In the 60s and into the 70s, rock acts might have released a couple of albums every year. By the 80s, it was an album every couple of years, accompanied, of course, for maximum profitability, by the world tour and its videos and T-shirts. In the late 70s, WEA and CBS really started to assert themselves in Australia. The early 80s’ double-boom of local pub rock and post-punk rock was a case of major labels versus DIY indies, mainstream media and broadcasters versus a burgeoning alternative. Even indies like, say, Missing Link, Phantom, Hot, Waterfront and Red Eye at least sustained to the extent of creating a sort of sound or legacy. The transition to grunge, bubbling up from the alternative underground after the bankruptcy of corporate rock, was greatly facilitated by PolyGram, with its investment in labels like True Tone, rooART and Red Eye. But rock by this time had lost its primacy, with the entrenchment of multi-cultural media and electronic dance music, hip-hop, world music, acoustic/roots music and many other niche markets. The other transition of the period is from vinyl to CD. As soon as the early 90s, vinyl is completely dead except in the hands of the new rock stars, remix-DJs. Part 6/ ENDGAME: Mid-90s to the Present Day, the killing of the record business at the hands of the internet, as the net undermines all the principles of copyright protection on which the business has thrived for the whole last century. The biggest corporate reconfiguration since the 50s leaves the multi-nationals – Sony-BMG, Warner-Festival and Universal – clinging on for dear life. The feeling in the record business today is worse than that in the auto industry; it’s a bit like the tobacco industry must have felt in the 1980s. NOTE ON IMAGES: They have been selected not so much as to directly illustrate the story at hand, especially as the narrative progresses - because so often the iconic album sleeves, for example, have been seen to death - but rather to act as a sort of counterpoint, and very often on the basis of less so the music in the grooves than the records' design and artwork. |