|

SOUL DEEP

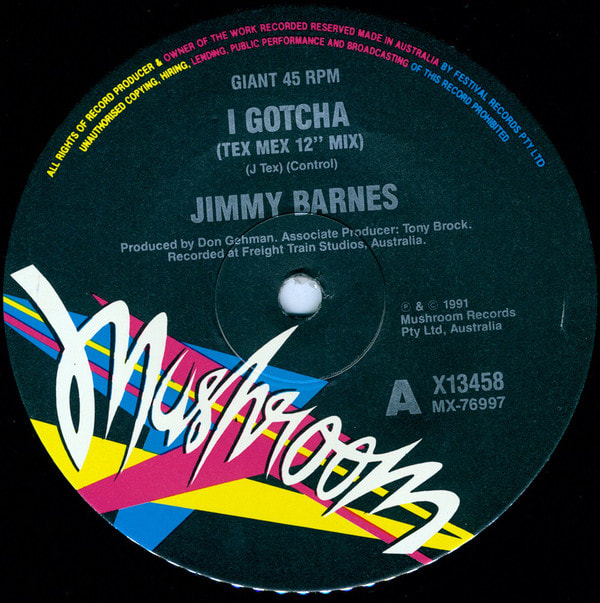

Jimmy Barnes (Mushroom) The difference, for artists, between influences as stated and influences as felt is perhaps not unlike the difference between the discs critics like on the page and the ones they actually like to listen to at home. Critics know - or at least ought to know - that just because a disc might be aesthetically Indefensible doesn't mean to say it can't be enjoyed. And artists sometimes cite influences because they're the influences they'd like to have. Jimmy Barnes has long claimed that the great Sixties soul men - like Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding – were his major vocal influence. It would be a misnomer, however, if this album was actually billed as a tribute to his roots. Barnes grew-up in Adelaide in the early Seventies listening to the British 'heavy' rock of the day, and his initial experiences as a singer were in covering material by the likes of Uriah Heep and Deep Purple. It's easy to imagine Barnes even at the outset of Cold Chisel imagining himself as some sort of new Paul Rodgers (of Free, then Bad Company). But it's almost impossible to be a rock musician and not sooner or later realize that black music is where almost everything comes from, and Barnes, of course, has a gravelly timbre and blood-curdling scream, which are qualities so often associated with white approximations of soul music. Yet while Barnes can thankfully now put his abominable version of "When A Man Loves A Woman" behind him, he still seems to be coming to terms with this thing called soul. If he's ever been conscious of continuing a Geordie tradition (he was born in Glasgow himself), he would appear to owe more to the Bon Scott/Brian Johnston rock’n’roll side of it than the black R&B-flavored side, which runs from Eric Burdon to Frankie Miller Barnes obviously learnt some lessons doing "When A Man Loves A Woman." Percy Sledge would have been horrified, it was all one long Scream - 'heavy-handed' is putting it mildly - and, well, you can't know joy if you don't know pain, and so the song was flattened-out into nothing. On Soul Deep, Barnes measures his delivery to a much greater degree, and gets a far superior result. Recorded at Barnes' home studio on the farm at Bowral, and produced by Two Fires' Don Gehman, Soul Deep (title thanks to the Box Tops) contains twelve tracks, most of which will be familiar as songs even to the uninitiated, the exception being the first single, "l Gotcha," an obscure Joe Tex gem. The rule of thumb here is that Barnes seems to be more at home in Memphis than Detroit, on material from the Stax vault rather than Motown's, as Stax was always funkier and grittier, its vocalists (Otis, Wilson Pickett, Joe Tex) prone to pyrotechnics. Why exactly he's bothered with orchestrated stuff like Diana Ross's "Reflections" and "Aint No Mountain High Enough," and Jackie Wilson's "Higher And Higher," is hard to say, although it can be said, he makes a fair fist of Stevie Wonder’s "Signed, Sealed, Delivered, l'm Yours," and even "River Deep, Mountain High" compares favorably to the original (if only because Tina Turner was always pretty much just a shouter herself too). Barnes originally covered Jimmy Cliff's "Many Rivers To Cross," as he did "When A Man Loves A Woman," on the Barnestorming live album, and it reappears here perhaps by way finally getting it right, which save for lame female backing vocals, it almost does. This good work, however, is promptly undone by the blockbuster ballad duet with John Farnham, on Sam & Dave's "When Something is Wrong With My Baby," due to its suffering for the sort of excess of yore. lt may be that it's a fine line between pyrotechnics and histrionics, but this just sounds forced. Although his version of latter-day Memphian Al Green's "Here l Am" reveals Barnes's real weakness - a lack of delicacy and melodiousness - it's on classic Stax fodder like "l Gotcha," and another Joe Tex side, "Show Me," that Barnes really lets fly. He is even convincing on the gospelesque passion of Wilson Pickett's "Found A Love" and Sam Cooke's "Bring it On Home To Me." Still, Jimmy Barnes isn't a soul singer, he's an artist who at best creates a scintillating hybrid of his own hard rock roots and soul influences. To the purist, this album will be entirely gratuitous, but it must be counted as a success if, as the Rolling Stones used to claim was their greatest aspiration, it serves as an advertisement for the original black artists. As for Barnes himself, one suspects that when he properly reconciles the two strains that run through him, we will hear his best work. |