|

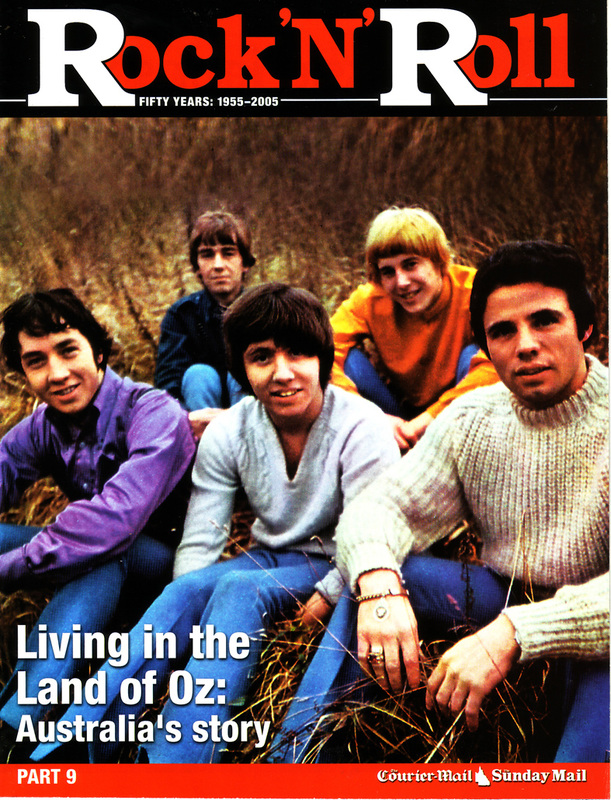

CONQUERING THE CRINGE, on the emergence of Australian music, from Sunday Mail special magazine series celebrating 50 years of rock'n'roll, 2005

|

|

When rock’n’roll exploded by that name in the mid-1950s, it wasn’t as if there hadn’t been any warning. For the some time, rock’n’roll was a revolution brewing in American music’s underclasses, and it coalesced with the electrifying fusion of these grass-roots genres: blues, gospel, R&B and hillbilly. In Australia, the birth of rock’n’roll is easier to pinpoint – it was in 1955, when the movie Blackboard Jungle opened here sporting Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” as its title song. Overnight, so the legend goes, Johnny O’Keefe, the once and future King of Australian Rock’n’Roll switched from impersonating Johnnie Ray to Bill Haley. For a long time, the orthodox view of Australian rock was that it was second-rate, a cargo cult, a mere colonial echo of the ‘real thing’: O’Keefe was an imitator of white American imitator of black Americans. Billy Thorpe was an imitator of young white English boys imitating old black American bluesmen – and he was an English migrant anyway! Yet even if Australian music ever did lag behind the international cutting edge, by the late 70s it had overcome the Tyranny of Distance and/or cultural cringe to such an extent that, in Brisbane band the Saints, it actually anticipated the world-wide punk uprising. A revisionist view of history further suggests our old inferiority complex was always misplaced anyway. After all, the story of pop generally is one of appropriation, adaptation and regeneration. The idea of authenticity in music is outmoded when survival itself depends on cross-pollination. People forget that the Beatles themselves - all British rock - was also the spawn of a cargo cult, and it is perhaps precisely because Australia was apparently so far removed from the supposed sources that our music mutated into such a distinctive, ultimately original hybrid. Ultimately, by the 1980s, Australia was the world’s third-largest producer of rock music, even though we were only its ninth biggest market. Long before the idea of ‘Aussiewood’ suggested we had any sort of film industry or tradition, rock’n’roll was the export that put us on the global pop cultural map. In 1985, our music export earnings were worth $10m; by the early 90s, that figure had grown ten fold and it’s still growing. But for all the palpable disadvantages Australian music still battles, like our isolation and tiny population/market base, right from the start we enjoyed one great advantage – we speak English. Rock is an English-speaking medium, which is why European music is only now catching up with Australian. If it’s impossible to define an Australian Sound as singular as, say, reggae is to Jamaica, our music might best be compared to the way we speak the same language as the US and the UK but, just like both those countries, with our own unique accents, rhythms and vernacular. In Australia in the early 50s, local country music and jazz alike were booming. Les Welch was our closest thing to a pre-rock sort of jump blues bandleader. But if the leap from hillbilly to rockabilly, as the terminology suggests, was not great, in Australia the bush ballad did not feed into rock’n’roll. Some young modern jazz musicians moonlighted in rock’n’roll bands and in doing so elevated them (notably Johnny O’Keefe’s band the Dee-Jays), but more typically the music was thin. It didn’t help, of course, that there was next to no infrastructure, expertise or even equipment in the country - only an audience. As another oft-repeated legend goes, Col Joye built his own electric guitars based on photos of American bands. There were no record companies. EMI’s Australian branch office had long enjoyed a conservative monopoly that was only just beginning to be challenged by new local labels like Festival. Still the sole Australian major (if now as part of Rupert Murdoch’s global empire), the fledgling Festival signed Johnny O’Keefe and an industry was born. Along with Slim Dusty, O’Keefe proved Australia needed to hear its own voices. Australian stars like O’Keefe and Col Joye would get Qantas stewards to bring American records in for them so they could look for songs. O’Keefe’s signature tune, “The Wild One” aka “Real Wild Child,” his breakthrough hit of 1958, was one of the few songs he wrote himself, and conspicuously it is the only song of the era that had real legs, having been covered by Buddy Holly, Joan Jett and Iggy Pop. Australian artists could sing rock’n’roll but, with few exceptions, no record company was going to let them write their own songs. But this was no different to the music business in America or Britain – at least until the Beatles and Bob Dylan changed everything in the mid-60s. Australia reacted to the Beatles exactly the same way America did, not least of all in inspiring hundreds of surf instrumental bands to scramble to grow their hair and get a singer: What’s the cargo cult now? In a post-Beatles world, Sydney responded quickly with Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs and the Easybeats, but by 1965, the pendulum had swung to Melbourne. This great intercity rivalry has coloured the history of rock in Australia as much as it has so much else (Brisbane has largely remained a primary producer). In 1965, more mod Melbourne was home to a huge suburban dance circuit, national TV shows and teen magazine Go-Set, and save for a few short-lived interruptions, it would reign indisputably as Australia’s music capital for the next decade. The rest of the world missed out in 1966 when Melbourne’s Loved Ones hit with “Everlovin’ Man,” a record as stunning as any made anywhere at that time. ”We used to laugh, because we used to win awards for originality,” keyboardist Ian Clyne told me in 1981, “but we were trying to sound like the Stones or the Yardbirds like everybody else! - it was just that we couldn’t do it because we came from a different direction, from jazz.” (“Everlovin’ Man” came out the way it did because Clyne had just got a new-fangled Hohner electric piano.) Like many bands including the Easybeats and the Masters Apprentices, who moved over to Melbourne from Adelaide, the Loved Ones were ten quid tourists (‘New Australians’; migrants) and they had a recording deal with one of the new regional independent labels that had sprung up to do the job the majors wouldn’t. Clean-cut folk quartet the Seekers had to leave their original label, Melbourne indy W&G, and join EMI before they could break out onto the national, and later international stage. When the Easybeats, driven by the brilliant songwriting team of Harry Vanda and George Young, made the pilgrimage to Mecca, Swinging London, they instantly delivered an international hit, the classic “Friday on My Mind,” but they fell apart in the quest to find a follow-up. Still a precedent was set. For all the quality of much of Australia’s early ‘beat’ scene, few acts transcended ‘one hit wonder’dom, including the Loved Ones. This was less for lack of talent than resources, or more particularly, major record companies willing to do something more than merely relay the latest overseas hits. Band after band, including the Bee Gees, left Australia, and only the Bee Gees didn’t crash and burn on Mother England’s shores. By 1968, sales of albums had surpassed those of singles overseas. Australia didn’t even get albums charts till 1970. This is where the Lag set in. In the late 60s, we didn’t do acid rock, we did bubblegum, because that’s what increasingly active new multinational labels like CBS (now Sony) saw as a viable. Squeaky-clean Johnny Farnham was much preferred to, say, guitar anti-hero and old Brisbane boy Lobby Lloyd’s wild Purple Hearts, or the Missing Links. Not until 1969 did we get a psychedelic hit (“The Real Thing”) or a Vietnam song (“Smiley”). After Monterey at the height of the Summer of Love in 1967, followed by Woodstock in ’69, we didn’t get our own first rock festival till Ourimbah in 1970 - and then most of the bands on the bill, the cream of Australia’s progressive rock underground, were still without recording contracts. Billy Thorpe declared bankrupt and repaired to Melbourne to reinvent himself as the bellowing new King of Oz Rock. By the time the first Sunbury, the defining Australian rock festival, was held on a farm north of Melbourne in 1972, it was a symptom of a whole new renaissance: The early 70s in Australia was like the late 60s we didn’t really have. Sunbury was no mere Australian Woodstock; it was more akin to Altamont, or indeed, a scene from Mad Max. A new wave of acts, including Thorpie and Chain and Daddy Cool, was straddling the singles and albums charts alike. “High-energy heavy metal boogie bands,” they were called by Anthony O’Grady, editor of new national magazine RAM, and the monstrous mutation of the blues they belted out became the foundation for pub rock to follow. Australia’s bodgies had always been more than a match for Britain’s Teddy Boys, and now our sharpies went a step beyond skinheads. Songwriting was rapidly maturing too. In 1969, two of the biggest and best Australian hits were “St.Louis” by the Easybeats, and “Arkansas Grass” by Axiom. Obviously we were stricken by some sort of identity crisis. By 1971, however, with “Black & Blue,” Chain actually took our convict heritage Top 10! Said Peter Head, leader of Adelaide’s Headband, “There were a lot of folk singers around then too, so we all got into songs with words that meant something. It was the first time anyone used Australian place names in songs. I remember having arguments with people who said you can’t use Australian names in a song, they sound daggy.” Again, the rest of the world missed out when classics like Spectrum’s “I’ll Be Gone” and Blackfeather’s “Seasons of Change,” or Healing Force’s “Golden Miles,” were doomed to remain domestic. But maybe we all missed out because so many obviously significant talents still failed to find any longevity. Thus was Michael Gudinski’s great promise when he launched Mushroom Records out of Melbourne in 1973: that Australian rock could be sustainable, a band should produce a body of work. But if Mushroom initially struggled, it was cocky young glam rock outfit Skyhooks that saved its bacon in 1975, and helped establish it as such a force that it virtually kept its distributor Festival afloat. Glam rock may have peaked in its British homeland a couple of years earlier, but we were (still) suffering the Lag. Australia had just got colour TV and the ABC in Melbourne launched a new show called Countdown. Hosted by Molly Meldrum, Countdown quickly became the yardstick in Australian music, and it enjoyed a golden era populated by such glam stars as Skyhooks, Sherbet, Hush, AC/DC, TMG, JPY and Marcia Hines. With the inception of 10 o’clock closing, the live circuit was by now moving into pubs. Skyhooks’ innovation was songs that made specific local references. But maybe AC/DC say more about us, even though most of the members were Scottish migrants and even though Bon Scott’s lyrics were very universal, because the band was shaped by the do-or-die Australian circuit, and its sound, transcending the literal, captures the deeper contours, colours and textures of life in this country. “Long Way to the Top” is our rock national anthem. AC/DC was George Young’s revenge, the band formed by his little brothers that wouldn’t repeat the mistakes the Easybeats made. And indeed, today, AC/DC trail only the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and the Eagles as the fifth-highest selling rock act of all time. (At the same time, the anti-AC/DC, LRB - Little River Band - proved it was possible to sell coals to Newcastle when they became the first Australian band to crack the US Top 10.) In the late 70s, punk and disco were the not-so-equal if opposite reactions to a world tightening in tune with then-Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser’s famous dictum, Life wasn’t meant to be easy. Two bands that began their careers as migrant kids in Brisbane – the Saints and the Bee Gees – were instrumental in launching the two genres. In an epochal traversal of the cultural cringe, the Saints put Australian rock on a parity (finally) with its English and American cousins. It’s the mark of an idea whose time has come, when people in isolated pockets around the world simultaneously start thinking the same thing, and that’s how punk happened, with the Saints drawing on much the same avant-primitive sources at the same time, if unwittingly, as the Ramones in the US and the Sex Pistols in the UK. But just as Australia tended to dismiss disco as fit only for “sheilas, wogs and poofters,” punk too was spurned. After they self-financed their debut single “Stranded” in 1976, the Saints were signed by EMI in Australia but only on the insistence of head office in London. The Australian music industry, after all, was only just really starting to get its shit together in the late 70s; the last thing the baby boomers needed was a bunch of snotty young punks coming along telling them they were all boring old farts. As an extension, indeed a consummation of existing principles, pub rock was much more palatable to most everyone, including, importantly, the new commercial FM radio stations. Thus was a schism born - mainstream/alternative - that has characterised Australian music ever since. Australia cosumed lots of but produed almost no disco, excepting Doug Williams Austral Funk Machine, Dark Tan and a handful of others. By the late 70s the pendulum was swinging back to Sydney, where powerful new agencies like Dirty Pool and increasingly confident multi-national majors like WEA were based. By the turn of the decade, Australian music was enjoying a boom as big as it ever has. Cold Chisel epitomised the sound of the suburban beer barns, Don Walker’s incisive songs picking up where Richard Clapton left off, and clearing the path for Paul Kelly and others to follow. The inner city was sanctuary to the more broadly vilified post-punk push. But if the live circuit, on which all our music’s strength was founded, was beginning to shrink by about 1983 as a result of the introduction of, among other things, random breath testing, the new challenge was off-shore. The suburban/inner-city, mainstream/alternative, major/independent divide became even more pronounced; now it was America/Europe too, and cocaine/heroin. After Men At Work’s “Downunder” was a surprise worldwide hit in 1982, bands like INXS, Midnight Oil, the Divinyls and Crowded House stormed the US and rode the MTV wave to enduring success. In another universe altogether in exile in Europe, acts like Nick Cave, the Go Betweens and the Triffids laid the foundations for an arguably more influential impact on the music world. Some people have been mourning the death of the pub circuit for twenty years, but to this day it’s never gone away, just spread itself thinner. In the greed-is-good era of 80s’ corporate rock, or stadium rock, Jimmy Barnes and Johnny Farnham were both born again, but conspicuously, both have remained steadfastly domestic phenomenon while their supposedly spastic siblings in the underground were continuing to trickle up, to eventually become the true elder statesmen. That’s why grunge was no surprise to Australia when it exploded in the early 90s, because bands like the Saints, the Birthday Party and the Scientists had had a seminal effect in Seattle. silverchair were actually an example of a Lag the major labels still prefer to impose, but at the same time (in the same way that today Jet like to advertise their ‘older brother’ band Dallas Crane), there were bands like Spiderbait, the Cruel Sea and You Am I who marched only to their own drum. The Big Day Out became the new Sunbury on wheels. When the first BDO was held in 1991, Nirvana were actually supporting the brutalist Beasts of Bourbon. When the event added its own in-built day-nightclub the Boiler Room, it was a measure of just how deeply electronic dance music and hip-hop was biting into the traditional rock market. Letting Nick Cave get away may be one of Michael Gudinski’s great gaffs, but one of his great coups – though no-one thought so at the time – was signing Kylie Minogue. In an increasingly fragmented music scene in the 90s, Kylie became one of our rare defining icons, not least of all perhaps because actually she’s lasted longer than fifteen minutes. But the more things change, it seems, the more they stay the same. Initially, Australian record companies couldn’t see anything in Savage Garden either. Even grunge was really just Oz rock by any other name. So the Brisbane duo took itself to America and ended up selling ten million albums world-wide. After two local Number One singles in 1997, Savage Garden’s debut album went to Number One and stayed there for fourteen weeks, longer than any Australian album since the Skyhooks’ Living in the 70s some twenty years earlier. Nowadays, you’ve just got to do it yourself. Whether you’re Australian, American or Swedish, there’s no sitting around waiting for record companies to make it happen any more. Today, anyone can cut a potential hit record in their bedroom; today, all music’s great strength is the application of that central punk ethic: do it yourself. |