PLANTING SEEDS: BACK TO THE BALLROOM

|

Extracted from the book Cultural Seeds: Essays on the Work of Nick Cave, edited by Tanya Dalziel and Karen Welbury and published by Ashgate in the UK in 2009 (BUY it here). I was semi-reluctant about writing this piece in the first place because i think there's just TMI on Nick Cave these days, but was pleased to try and shed some (non-academic) light on his important early musical-formative years

|

|

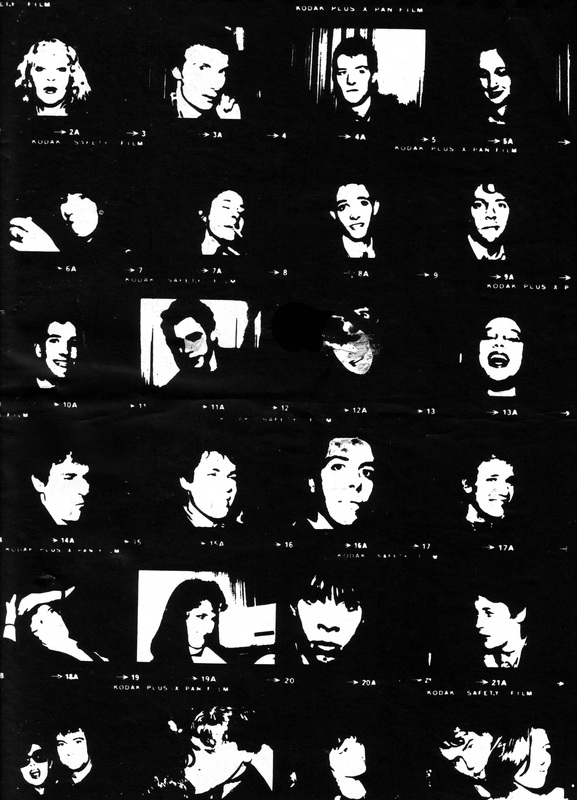

I first met Nick Cave in Melbourne in early 1978 when we were both, daresay, players in a new music underground that was still so small that everyone knew each other. Cave was fronting the Boys Next Door, his high school band going semi-pro, and he was even then a shining star; I was a budding music writer fresh down from Brisbane, who, like the Boys Next Door and the other maybe seventy or so people who went to see them every Tuesday night at the Tiger Lounge that winter, had been inspired into action, or at least goaded on, galvanised, by the punk rock explosion of 1977.

The mid-to-late 70s was a turning point for rock music and all popular culture. Cave himself has often referred, only half-jokingly, to “when we fought the big one in 1976 or ’77.” (1) For a generation like Cave and myself born in 1957, or at least tiny isolated pockets of us all round the (pre-internet) world, there was something new in the air we were picking up on. |

|

Punk rock as it came to be broadly identified at that time was largely thanks to the short, incendiary career of the Sex Pistols. Punk as a genre was the enema superstar rock had to have as it became ever more bloated and irrelevant in 1975/’76. The buzzsaw call-to-arms first heard in late ’76, in the Ramones’ debut album and the Sex Pistols’ “Anarchy in the UK,” and the first single by Brisbane band the Saints, “Stranded,” was a necessary part of that process. But beyond that, the post-punk period (1978-c.1984) was perhaps even more fertile, because after punk wiped the slate clean, it was as if everything opened out again: We had gone through ground-zero and now felt free to re-start again. This was a lot of the feeling in that small scene in Melbourne in 1978 – Anything Goes. For me, it was an exhilarating time. Personal nostalgia aside, it was an extraordinary time. It was quite enough just to be part of a groundswell, because it seemed very real and very strong. Even if more broadly it only seemed to incite fear and loathing, that, of course, was a large part of the cult appeal anyway (Us against Them). For those of us of this Blank Generation, to use Richard Hell’s phrase, the period was a rite of passage that ironically created our future even as we joined in the Sex Pistols’ chorus, “No future”, and we were all shaped, to differing degrees, by our common experience. For Nick Cave, the period was doubly dynamic, formative, because it was around this same time – late 1978 – that his father died. Cave has remembered how it all set a tack for him: "The things I love, the things I hate, the things that really affect me - I felt those things forming, right down to the type of music and literature I liked. I don't feel that they've progressed particularly since that time, and that was pretty much the time my father died, and I think that's not coincidental." (2) With this article, I want to go back to that time and place – go back, so to speak, to the Crystal Ballroom, the Melbourne venue that gave Nick Cave his first great stage, in 1979 – in order to try and recall just what it was in the air that so fired us all up. Because for all the serious discussion that Nick Cave inspires these days, what tends to get a bit overlooked, I reckon, is music itself, especially the music that inspired him to take up music in the first place, and even for all Cave’s quite reasonable claims on Rennaissance Man status, he remains, first and foremost, a musician, a singer and a songwriter. That he spent most of 2007 working on the side-project Grinderman, strapping on an electric guitar for the first time in his career and just rocking out, is an indication of the primacy of music to him: This was Nick just having fun. But like Bob Dylan, it’s his lyrics and literary position that have drawn the overwhelming proportion of comment. Yet as Dylan said in his 2005 memoir Chronicles, “Musicians have always known that my songs were about more than just words, but most people are not musicians.” (3) I want to go back to the Crystal Ballroom to recover the songs and bands that I too remember from all those parties and gigs and German afternoons so long ago; the music we all came to love and hate together; the values that have underlined the best of what we’ve all done since then. Internationally, Nick Cave seems to have been born in 1980, when he arrived in London with the Birthday Party, the band the Boys Next Door became after guitarist Rowland Howard joined and they left Melbourne. Even the most well-informed of rock scholars in other parts of the world has an incomplete understanding of Australian music and its history. This would be reason enough, I would have thought, for anyone to want to delve into those early years in Australia, but all the more for me given that I was there and have a certain amount of insider knowledge. Obviously Melbourne in the late 70s was a crossroads for many of us. I had come from somewhere similar to Nick Cave (was an art school drop-out who’d been born in the same part of rural Victoria), and I would end-up, in one respect, unfortunately, in a similar place (taking hard drugs for too long). I’m not sure if like me Cave was pushed towards figurative expressionism at art school as a reaction against the prevailing self-indulgence and elitism of conceptual art, but I know other people from the punk wars who were. Much of this piece is obviously drawn from direct personal experience. |

|

In my vocation I have produced a number of CD anthologies, and in a way maybe I always saw this article as something like the liner notes for a hypothetical soundtrack album of Nick Cave’s formative pre-history. It’s true, there has been, in 1998 and 2004, two CD volumes of Original Seeds, ‘Songs that inspired Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’, and Cave himself has performed many cover versions throughout his career and released an album of them, Kicking Against the Pricks, in 1985. But this is about before the Bad Seeds: From Concrete Vulture to the Boys Next Door to the Birthday Party. It is a musical biography of the artist-as-gormless-adolescent. The tracklisting for that hypothetical double-album, then, follows, should any readers wish to load it into their iPod: SIDE ONE “Blitzkreig Bop” – Ramones (1976) “Anarchy in the UK” – Sex Pistols (1976) “Stranded” – Saints (1976) “TV Eye” – Radio Birdman (1977) “Louie Louie” – Iggy and the Stooges (1977) “Gloria” – Patti Smith (1976) “These Boots are Made for Walkin’” – Nancy Sinatra (1966) “All Tomorrow’s Parties” – Velvet Underground (1966) SIDE TWO “I’m Eighteen” – Alice Cooper (1971) “Next” – Sensational Alex Harvey Band (1973) “Andy Warhol” – David Bowie (1971) “Berlin” – Lou Reed (1973) “Personality Crisis” – New York Dolls (1973) “The Model” – Kraftwerk (1978) “Re-Make/Re-Model” – Roxy Music (1972) SIDE THREE “Shivers” - Young Charlatans (1978) “Curiosity” – Crime and the City Solution (1977) “Do that Dance” – Primitive Calculators (1979) “Shot By Both Sides” – Magazine (1978) “Frankie Teardrop” – Suicide (1978) “I Need Two Heads” – GoBetweens (1980) “I Want to Scream” – Laughing Clowns (1980) “Rooms for the Memory” – Whirlywirld (1979) SIDE FOUR “Non-Alignment Pact” – Pere Ubu (1978) “No Birds Do Sing” – Public Image (1979) “(She is) Beyond Good and Evil” – Pop Group (1979) “I Love You, You Big Dummy” – Captain Beefheart (1971) “Sad Dark Eyes” – Loved Ones (1966) “Loose” – Stooges (1971) “Mystery Plane” – Cramps (1980) At the start of 1978, when I first saw the Boys Next Door, they had been playing publicly for barely six months, and they were as a likely a prospect the Australian new wave was going to throw up, could have been and in many ways were the next cab off the rank after the Saints and Radio Birdman, Australia’s twin prophets of punk. When I first saw them – at Preston Institute on February 24, as the astonishingly deep fansite archives on the internet now tell me – the thing that was immediately refreshing about them was that they sounded nothing like the Ramones/Sex Pistols axis whose influence had quickly become pervasive and stultifying. Nor even, closer to home, did they echo the Saints or Birdman, both of whom had had a profound impact on them. In a way, they reminded me of the GoBetweens, whose first-ever performance I’d seen in Brisbane just weeks before. Fey boys touting acoustic guitars and the influence of Bob Dylan and the Monkees hardly fitted the rapidly coagulating punk stereotype, but that’s precisely why they impressed me: an anti-orthodox DIY adventurousness. The Boys Next Door were similarly individualistic, a sort of glam-punk power-pop garage band who, if anything, were reminiscent of Roxy Music – which was fine by me, because like the Boys and so many other footsoldiers in the Big One, I was an old glam rocker from way back, and I felt a sense of unfinished business about the experimentalism of bands like Roxy. The Boys themselves often asserted that it was because they had deeper roots in glam rock, which in so many ways were the roots of punk, that they weren’t blinded by punk when it came along as such in’ 77. They didn’t have to do an about-face, as many struggling ‘old wave’ bands did; they were merely vindicated to press on even harder. “We didn’t know what we were,” Mick Harvey told me in the early 90s, “we’d been doing this stuff which was the precursor to punk, to some degree, so when punk came along, we thought, Oh, that’s what we must be, but of course it wasn’t. We twisted what we were doing a bit.” (4) When I first saw them, the Boys’ first single, a cover of Nancy Sinatra’s 60s’ hit “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’,” had just been released. “Boots” might have seemed a bubblegum/novelty song at the time, but the trash aesthetic was always part of punk’s program too. Yet even as the band hurried to outgrow what they doubtless saw then as the embarrassing infantilism of this and some of their other early covers (they were already phasing “Boots” out of their set), many of those influences would eventually come back to haunt Nick Cave. In a good way. Musically, the early teenage Nick Cave grew up in the shadow of his oldest brother Tim, whose taste ran, basically, to progressive rock, the high hippie form of the likes of Pink Floyd, Genesis, Yes, Jethro Tull, et al. (5) Glam rock was in one way a younger generation, tail-end baby boomers, thumbing its nose at its metaphorical older brother. When the young Nick found some things for himself like Marc Bolan and T.Rex, or Alice Cooper or the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, it was disdained as upstart trash by all the Big Brothers of the world. But it egged us all on and it formed a basis, in 1974, for the Caulfield Grammar garage band in which Cave, Mick Harvey (who remains Cave’s Sancho Panza to this day) and drummer Phill Calvert first came together. Nick has remembered that when the band, known at one stage as Concrete Vulture, practised and played school dances occasionally during 1974/5, its repertoire consisted mainly of Alex Harvey covers with a few Alice Cooper numbers thrown in as well. (6) Scotsman Alex Harvey and the American Alice Cooper were both extremely theatrical and narrative-based, and can be categorised as both glam and shock rock. Glam ran from Bolan and Bowie to Slade and the Sweet, even Australia’s own Skyhooks; the shock part added to glam’s sexual ambiguity an aspect of camp/Gothic horror, going all the way back to Screaming Jay Hawkins and up to Black Sabbath. Clearly all this has fed into Nick Cave as we know him now. If it wasn’t Alex Harvey who introduced Euro cabaret to Cave – the title-track of Harvey’s second album was a version of Jacques Brel’s “Next;” and the influence of Euro cabaret is, again, obviously still strong in Cave – it was the Doors, who covered Brecht and Weil’s “Alabama Song,” and who we all listened to. Concrete Vulture fizzled out after the boys left school. But during 1976, with Cave now at art college and the first stirrings of punk rumbling on the horizons, Cave, Harvey and Calvert came back together, now with bassist Tracy Pew, another old cohort from Caulfield Grammar: This was the quartet that would become the Boys Next Door. Pew had been learning the rudiments of his instrument from his best mate in suburban Mount Waverley, Chris Walsh, and all this would have a profound impact. Walsh was the kid who played Cave and the band the records that really anticipated punk. “We’d get to hear all this stuff at his house,” Mick Harvey told me. (7) It has to be explained that this was a time long before unlimited access. There was a strict hierarchy of taste in mid-70s rock and it palpably excluded, ironically, the three acts who would ultimately change everything: the Velvet Underground, the Stooges and the New York Dolls – the three pillars of pre-punk. Beyond Bowie and Lou Reed though, these records, at the time, were hard to get. If you were quick you could get copies from the Australian Record Club of the two New York Dolls albums and Iggy and the Stooges’ 1973 third and last album Raw Power. Picking up on these sorts of records certainly changed my life, as it also did the young Ramones and the Saints and Radio Birdman and Chris Walsh and the nascent Boys Next Door and the Sex Pistols and the Clash and everybody else. They opened a door. Punk was a reaction against all the Big Brother hippy orthodoxies of the 1960s that in the mid-70s still dominated the charts. Peace and love had failed. This was the antithesis of all that. Nick Cave has said that Raw Power changed his life after he bought a copy because he liked the cover (8), but it seems more likely that Chris Walsh played it to him. The necessary aesthetic imperative was back to basics; from the bloated rock opera to the short, sharp attack; from long hair and beards and flares to razor cuts and stovepipes and winklepickers. We all hated Supertramp and Fleetwood Mac and Rod Stewart and Rick Wakeman and the Stones and all the boring old farts. Import copies of the Ramones’ first album started trickling in to Australia in mid-1976, after Patti Smith’s debut Horses had arrived earlier in the year. Chris Walsh played The Ramones to the still-unnamed Boys Next Door. Cave, like all of us, knew the Big One was on. The Ramones, who had emerged out of the same lower Manhattan bar as Patti Smith, CBGBs, reduced rock to its elemental minimalism and gave punk its buzzsaw blueprint. In quick succession, by October, Brit-punk had hit wax for the first time, in the form of the Damned’s debut single on Stiff Records, “New Rose,” and in Australia, the Saints had self-pressed (as we used to say back then) a debut single, “Stranded,” and Radio Birdman advertised via mail-order a debut EP, called Burn My Eye. In November, the Sex Pistols’ “Anarchy in the UK” came out. It was even released by EMI in Australia. I bought a copy from Woolworths before it was withdrawn from sale. For me though, the Saints, who I met in high school, had already turned my head; when “Stranded” started the fire it did, I dropped out of Brisbane Art College and started writing about this new music movement. A vast bum rush, the Big One, took place in 1977. Punk rock became the year’s international moral panic of choice. The Sex Pistols would barely survive into 1978, but their reverberations are still sounding. For the Boys Next Door (now having taken that name), the real or strongest inspiration, however, was less a crackling signal on vinyl than ones much closer to home – seeing live in Melbourne, first, Radio Birdman, and then, much more importantly, the Saints. This was living, breathing confirmation of what was possible, even out of little old Australia’s supposed backwater. Nick Cave was a conspicuous headbanger down the front at Radio Birdman’s first Melbourne gigs in March 1977. But compared to the almost militaristic Birdman, the Saints were a truly mercurial force, and as soon as Cave saw them barely a couple of weeks later, as he has said himself on numerous occasions, his life was changed. He walked away a different person. (9) Three months after this, the Boys Next Door played their debut. Assisted by then-‘manager’ Chris Walsh, they played consecutive weekends in early August with the Reals, the band Walsh had got together with Ollie Olsen and Garry Grey. The first gig was in Mick Harvey’s Anglican minister father’s church hall in Ashburton, and the second, organised by 3SW DJ Bruce Milne, was a ‘Cheap Thrills New Wave Rock Show’ at Swinburne Tech, with a third band on the bottom of bill, the Obsessions, led by Rowland Howard. As evidenced by a surviving cassette tape recording, the Boys Next Door at Swinburne were unremarkable, musically. Their set was weighted 60/40 in favour of covers: a couple of Ramones songs, which are as easy to play as the few garage band standards they also did, like “Gloria” and “Louie Louie;” there was a version of Alice Cooper’s classic “I’m Eighteen,” which doubtless hung over from Concrete Vulture; and there was “Boots” and another relative novelty song, 50s’ R&B hit “I Put a Spell on You.” None of the five originals were terribly distinguished. But there was something about the band even then. The charisma of its front man must have had something to do with it. New York new wave band Blondie had scored a surprise hit in Australia, largely thanks to Countdown, Molly Meldrum’s weekly ABC pop program, and when they toured here in December 1977, they saw the Boys Next Door and ran off and told Molly to put them on his show. Molly didn’t want to know. He was typical of the baby boomers who ran the Australian music industry and felt only threatened by so-called punk rock. There was one music industry veteran-outsider, however, Keith Glass, who saw something in the BND, and he gave them their first ‘legitimate’ pub gig, supporting his own Keith Glass Band (or KGB), at the Tiger Lounge. Things moved quickly after that. Everything happens quickly when you’re twenty, even if it seems like an eternity at the time. After barely half a dozen professional engagements in 1977, the Boys Next Door played a hundred gigs in ’78. The Sex Pistols barely played so many in their entire career. The old-school Australian pub circuit, at its peak in the late 70s/early 80s, was fabled for breeding tough bands, from AC/DC to Rose Tattoo and Midnight Oil, and there’s no doubt that Nick Cave benefited for this demanding apprenticeship too. The Reals and the Obsessions quickly dissolved. Chris Walsh and Garry Grey carried on as the Negatives. Ollie Olsen and Rowland Howard got together with my flatmate Jeffrey Wegener, who’d drummed briefly with the Saints in Brisbane, to form a band called the Young Charlatans, who would have an enormous influence throughout the new Melbourne music underground. The Boys Next Door’s shifting range of covers tells a story in itself. By the winter of ’78, when they were in the studio recording a debut album and could play two sets a night as they did every Tuesday at the Tiger Lounge, they only had to pad it out with two or three, maybe four new covers. And those were a long way from Ramones songs. I vividly remember the band playing “Andy Warhol,” by David Bowie, and Lou Reed’s “Caroline Says.” They also used to occasionally do Iggy Pop’s “China Girl” (from his ’77 comeback solo debut The Idiot), and the New York Dolls’ “Personality Crisis.” These sort of songs were a bare-faced confession of where they were coming from. There was an explosion of new young bands at the time and most of them were doing nothing but recycling Ramones and Sex Pistols riffs. The Boys Next Door were already drawing from a deeper well, which was what allowed them the greater scope. Brit-punk, by 1978, was already approaching the dour Doc Martens-and-Mohawks stereotype, and certainly in Melbourne at the time, what I remember hearing a lot of was not the Clash or Buzzcocks or Stiff Little Fingers or Sham 69 or any of that. What I did hear a lot of – what was in the air – was the Berlin Quartet, as I like to call the four albums released in ’77 by Bowie and Iggy, the former’s Low and “Heroes” and the latter’s The Idiot and Lust for Life (all of which were recorded in Berlin). This, like the New York acts like Television, Richard Hell, even the early Talking Heads (art school graduates), pointed towards a more promising post-punk direction. Eno. The Saints’ third and last album of 1978, Prehistoric Sounds. Early singles by Magazine and Devo. ‘Oddities’ like Leonard Cohen’s Phil Spector-produced 1977 album Death of a Ladies Man, and Captain Beefheart’s 1978 comeback album Shiny Beast. Kraftwerk! – Trans-Europe Express and the brand new Man-Machine. There was even more Germania: people were going to see films like Auguierre and Kings of the Road. But again, first-hand experience cut deepest. Peers and rivals the Young Charlatans put the biggest frighteners on the Boys Next Door. Like the GoBetweens up in Brisbane, the Charlatans were precociously well-developed at a very early stage, and the Boys Next Door, who might have been the ultimate late bloomers, learnt much from them. The Charlatans per se peaked too early. They broke up in May 1978 after only thirteen gigs. Their last was co-headlining with the Boys Next Door a benefit for Pulp, the fanzine that Bruce Milne and I could no longer afford to keep putting out. (I went on as a sort of enfant terrible of the mainstream music press; Bruce worked with Keith Glass on his Missing Link label, and on his own Au-Go-Go label.) The Charlatans’ impact was felt far beyond that, for the Boys Next Door not least of all in the fact that guitarist Rowland Howard moved on to join them, to share songwriting duties with Nick Cave. Howard gave the Boys Next Door an immediate leg-up. His song “Shivers,” which was a staple in the Young Charlatans’ set, would become their second single, and he and Cave would greatly spur each other on. At the suburban beer barns where pub rock ruled, supporting bands like Australian Crawl or Icehouse or Cold Chisel, the Boys Next Door were booed and bottled. But at the Crystal Ballroom, Melbourne’s new mecca for new music, a faded old hotel in sleazy St.Kilda, they were like lords of the new church. Although, at that precise point in time, going in to 1979, not long after Cave’s father Colin had been killed in a car accident, they probably weren’t best band on the scene. It was time when every week seemed to bring a new record from overseas that was unlike anything you’d ever heard before, or another gig that topped the previous best gig any of us had ever seen, the week before. With songwriting split virtually 50/50 between Cave and Rowland Howard, the Boys Next Door certainly had no room left for any covers. Although, by any other name… Yet while it is probably true that at the time Cave and Howard were just trying to better each other’s imitations of their mutual latest favourite record from England or America, whether Pere Ubu, Public Image (Johnny Rotten’s post-Pistols band) or the Pop Group, at the same time, again, it was their very immediate peers and rivals who pushed them hardest: Whirlywirld (Ollie Olsen’s new all-electronic band), Crime and the City Solution (down from Sydney) and the Primitive Calculators. It may be, again, that a band like the Primitive Calculators, say, who are all but forgotten to rock history, were perfectly-formed in 1979 when the Boys Next Door were still grappling to find a voice. The Calculators were certainly the first band I ever saw play live with a drum-machine. But more than that it was their sheer raw intensity, spontenaiety and originality that gave the Boys Next Door a hurry-up. Whirlywird debuted at the Ballroom on New Year’s Eve 1978. Their sound had that sweeping, almost cinematic quality that everyone was starting to chase; within the space of a year, it had naturally (d)evolved into a looser, even more dynamic soundscape. Crime and the City Solution, with whom the Boys Next Door formed a mutual admiration society, contrastingly used bludgeoning repetition to back up front man Simon Bonney’s uncanny grasp of mystery and melodrama. Nick Cave copped a move or two off Bonney, there’s no doubt about that. But even as the Boys Next Door hit their most mannered and worse-still preening in their attempts to catch up with everything around them, the phase was also ultimately liberating because perhaps more than anything it was about deconstruction. As Captain Beefheart demonstrated – and everyone was listening to Beefheart – you could pull apart the most primal delta blues and put it back together however you liked, however seemingly dislocated. This approach keyed in with the first literary influences finding their way into the BND, with both Cave and Howard developing a taste for surrealism, absurdism. Religious imagery was also starting to appear in Cave’s songs. But most crucially it was understanding now that music was about carving out dynamic space, creating tension, that the Boys Next Door could finally get on with loosing the voice within. They had hit the proverbial glass ceiling. They couldn’t go on playing to the same adoring two hundred people every other week at the Ballroom. Like the Saints and Radio Birdman before them, and the GoBetweens, they were just going to have to get out of Australia. Mushroom Records released the Boys Next Door’s debut album Door, Door in May 1979, but after the single “Shivers” was barred from Countdown (for mentioning suicide), the label dropped the band. It may be one of Mushroom mogul Michael Gudinski’s great regrets, not that he let a talent like Nick Cave slip through his fingers, but that he had him and he let him go! Manager Keith Glass would now release the band on Missing Link, which was already putting out Whirlywirld and others. Glass put the band in the studio with the Cohen who be much more important to Nick Cave, in the immediate term, than Leonard Cohen, producer Tony. ‘TC’ would help hone the Birthday Party’s increasingly visceral sound. Cave was starting to dabble in narcotics. Having dropped all the covers from their set when Howard joined, the band introduced a new one, a version of Gene Vincent’s spooky 50s’ rockabilly classic “Cat Man,” which Keith Glass had played to them. On February 29 1980, the Boys Next Door flew out of Melbourne. When they landed in London, they were the Birthday Party (after Pinter or Tolstoy). Whirlywirld, the Calculators and Crime and the City Solution would soon follow; I left town myself too, bound for Sydney. Cave has remembered how with the Big One “my life seemed to open up a bit,” (10) but surely the great opening up had to be going to England in 1980. It was the making and the breaking of the Birthday Party. You can go all round the world only to find yourself. The Birthday Party were jolted into an almost self-anointed sense of purpose. Immediately they discovered that the grass wasn’t any greener at all. London was a miserable place and they had no money, and the music scene, such as it seemed, was an empty vessel of hype. Cave has related many times how it was a concert the band all went to see, a bill boasting the latest new flavours of the month, Echo and the Bunnymen, the Teardop Explodes and the Psychedelic Furs, and it was so bad, so insipid, this negative reaction was almost life-changing itself. (11) Cave was turned on though by one gig he saw – the Cramps. Keith Glass says that that gig had a huge impact on Nick. (12) Punk’s going back the garage was one thing; going back, as the Cramps did, to the swamp, where it all began, was something else again. In regurgitating rock’s most primal white trash/black magic origins, the Cramps pointed to a profound re-alignment of the garage band tradition. The Cramps were art and trash all at once, a collision of sex, death and rock’n’roll, and their impact was obvious in Cave’s descent into his early solo ‘Southern Gothic’ persona. Returning to Australia at the end of the year, after playing a meagre ten gigs in London, the band as if went back to the womb. Cave and Howard have both recalled how they got home and both, independently, rediscovered the Stooges – no doubt as an antidote to the pap they’d experienced in the UK. (13) One night at the Ballroom they played a whole set of Stooges songs just for fun. It was, again, a trigger like it was in 1975. Via the Stooges and the Cramps, the Birthday Party were finally finding their voice. Touring nationally with Missing Link labelmates the GoBetweens (now living in Melbourne), and the Laughing Clowns (the band former Saints guitarist Ed Kuepper had formed in Sydney with Jeffrey Wegener), the Birthday Party were again inspired to be at the centre of another extraordinary Australian explosion. Having seen how bad English music could be, and how good bands like the Clowns and the GoBetweens, and the Calculators and Crime could be, the Party were given a great injection of self-confidence. With Tony Cohen, they recorded Prayers on Fire that summer. It was indeed their first album. It remains a pretty good album, even if it is all over the place. The songwriting was wildly divergent. Shared between Nick, Rowland, Mick and Anita Lane (Nick’s girlfriend) and Genevieve McGuckin (Rowland’s girlfriend), it went from the ordinary to stunning. The only song written solely by Cave, “Nick the Stripper” was the standout track. The lead single, it introduces a hitherto unseen sense of grotesque humour, a self-flagellating self-portrait. “King ink,” however, co-written by Nick and Rowland, was the song that laid a template for the fully ripe Birthday Party to come, with its lumbering tempo, malignant sense of space and beguiling literary allusions. Although often charged with misogyny, the Birthday Party were rare among rock bands in not just giving their muses credit but involving them at all. The Rolling Stones may have written “Wild Horses” about Mick Jagger’s girlfriend, singer Marianne Faithful, but when she herself had a hand in writing “Sister Morphine,” she received no credit. Anita Lane and Genvieve McGuckin would both act as muses and fully-credited collaborators with the Birthday Party, and both would go on to work further with the musical extended family that grew out of the Birthday Party. Feeling cut loose anyway, the Birthday Party were able to totally abandon themselves to and into the music. Cave and Howard’s ever-growing heroin consumption further exacerbated a sense of being beyond the law. All this propelled them into a final phase that could only end in self-destruction. With Prayers on Fire having some impact in the UK in 1981, the Birthday Party stepped up the next level, returning to their previous average of a hundred gigs a year, and venturing into Europe. English bands just didn’t do that. On stage in 1981/’82, the Birthday Party, despite or perhaps because of their unpredictability, were at a peak, one of the most compelling and genuinely dangerous live acts ever to besmirch rock history. It was theatre of cruelty in action. They were about the only band ever to get away with covering Stooges songs, and that’s a list that runs from Radio Birdman to the Sex Pistols. At various times in ‘81/’82 they did three, “Loose,” “Funhouse” and “Little Doll,” and somehow they even managed to extend the ferocity of the originals. The Birthday Party’s supernova was largely facilitated thanks to a shift in the balance of power between the two main songwriters, Cave and Howard. Cave’s greater literary ambitions now started to take the ascent. As he became increasingly interested in narrative, he became increasingly disinterested in singing Howard’s songs, with their still quite surrealistic lyrics. Perhaps more to the point, as Cave’s writing went from strength to strength, Howard’s clearly wasn’t keeping up. Cave was already inheriting the mantle from Iggy or Keith Richards as rock’s next most likely casualty. Over the Australian summer of 1981/’82, the Birthday Party recorded Junkyard with Tony Cohen, the album so famously adorned with cover art by Big Daddy Ed Roth. I loved that because I grew up building Rat Fink hot rod model kits myself. Junkyard was a clattering, keening wail, an album mired in drugs, and again, despite some standout tracks largely written by Cave, as a whole it almost collapsed under its own weight. By early 1982, I was living in London myself, in a sprawling flat with the GoBetweens, and Cave and Tracy Pew came to doss on our couch. They had fired drummer fired Phill Calvert, who went on to join the dreaded Psychedelic Furs. They were going to move to Berlin, with Mick Harvey moving on to drums (Harvey was and is a brilliant multi-instrumentalist.) It was a sort of resolution in itself, going to Berlin, where all that music that had so inspired the Boys Next Door came from. And indeed, it would transpire to be the Birthday Party’s last stand. The band would teeter on for another year, but not before recording a pair of 12” EPs, The Bad Seed and Mutiny, the former of which stands as the Birthday Party’s penultimate distillation. “I would say in retrospect it was definitely a self-annihilating thing,” Cave once told me. “I mean, once we got onto the basic train of thought of Junkyard, it was impossible for us to go on forever like the Rolling Stones.” (14) Cave was already talking about an EP of covers of Walker Brothers songs even before the band went to Berlin. This was an indication of some of the new influences the Birthday Party were perhaps not quite equipped to accommodate. They were symptomatic too of another opening up. If two things were much more available in London than they were Australia, it was heroin and music, and Cave, like many of us, fed greedily on them both. I was working at the time in the legendary London record shop that wouldn’t give Nick Hornby a job, and it was my mission to steal every record I’d never heard, or previously dismissed due to punky immaturity. I resumed my research into the roots of rock’n’roll that had been so rudely interrupted by punk. Lots of other people seemed to be doing the same thing. If I’d already seen blues legends like Muddy Waters and Bo Diddley live in Brisbane, now I got more into the white man’s blues, country music. All the real roots of everything. When Cave and Tracy Pew did a radio interview in Germany around this time and spun some of their current favourite discs, that playlist, which included the Walker Brothers, Hank Williams, Van Morrsion and Kris Kristofferson (15), reads very much like the soundtrack the GoBetweens and I were listening to at our Fulham pad in London, the records I smuggled home from work. We were listening to Astral Weeks and Wolf King of LA and After the Goldrush and Return of the Greivous Angel and Music from Big Pink. When Cave did the NME column ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Consumer’ in April 1982, he listed under ‘Best Things’: Anita first, followed by Wise Blood (the film, the book), the Stooges, Caroline Jones, the Fall, Evel Kneivel, Johnny Cash, Samuel Beckett, George Jones, Tanya Tucker, Robert Mitchum and Big Daddy Ed Roth. On his ‘Deathlist’ he had Supertramp, Echo and the Bunnymen, the Teardrop Explodes, Stevie Wonder and some English rock journalist who’d given him a bad write-up. (16) These were Cave’s old and new loves and hates that were starting to make him feel limited by the Birthday Party. But the band had to yet play out its death-throes. For which Berlin still seems an appropriate place. When the Birthday Party went into the studio there in ’82 to record The Bad Seed, flying in Tony Cohen to help, it was the same ‘studio by the wall’, Hansa, where Bowie and Iggy recorded so much of their Berlin Quartet albums. Against a backdrop of German neo-expressionism, the film rennaisance and fin-de-sicle decadence, Nick Cave grew wings. He introduced a new cover to the band’s live set, the Loved Ones’ “Sad Dark Eyes,” one of the handful of fabulous Australian hits of the 60s that the rest of the world missed out on. The tighter the focus on Cave got, the better the Birthday Party became. The Bad Seed was the band stripping back to its most elemental: a sea of space, dark and threatening, underlined by the huge Harvey/Pew rhythm-section, punctuated by Rowland Howard’s “six strings that drew blood” (as Cave described his guitar-playing), and overarched by Cave’s increasingly convincing narrative voice. Rowland Howard’s songs were barely getting a look-in anymore. The band was falling apart. In early 1983, Jeffrey Wegener sat in on drums for a Dutch tour, allowing Mick Harvey to return to guitar. A short American tour after that was a magnificent disaster. In April the band were back in Berlin, at Hansa, recording Mutiny. In May, the band returned to Australia for a quick tour. I saw the show at the Trade Union Club in Sydney, and the 40-minute set was short but explosive. On June 9, at the Ballroom in Melbourne, they played a farewell show. It turned out to be the Birthday Party’s last gig. The band was dead. Long live the King. After a couple of gigs and recording sessions in London in late ’83 with the nominally named Cavemen, Nick Cave returned to Australia again for Christmas and played the ‘Man or Myth’ tour, out of which grew the first line-up of the band soon to be christened the Bad Seeds. Now as a solo star with a clearly delineated backing band, Cave built a line-up around the songs and styles he set. The only common element ever remains Mick Harvey. But just as Harvey’s brilliant drumming characterised the early Bad Seeds’ sound as it had the late Birthday Party, the bigger difference now was Cave’s moving to piano. Obviously, the type of music you can write and perform on piano is very different to that which a bass/drums/guitar rock’n’roll band can conjure up, however deftly. The piano would allow Nick Cave to start moving towards the more melodic, reflective, orchestrated sound that is now his trademark. Balladry. If, as has almost become a corporate slogan, Nick Cave doesn’t do happy, he does sad and angry, and the angry side is still very punk rock, electric guitar-oriented, it is the sad for which Cave is most widely liked, and that is based in the piano ballad. Still they’re all story songs, which play out dramas like little movies even without a video. Like all those songs beyond just “Boots” that the late Lee Hazlewood wrote and produced and performed with Nancy Sinatra, songs like “Some Velvet Morning,” a version of which Rowland Howard released as a single with Lydia Lunch in 1983, and “Summer Wine” and others. When Nick Cave programmed the English Meltdown festival in 1999, he put Lee Hazlewood on the bill, and this helped revive the maverick artist’s career. He also put Nina Simone on the Meltdown bill. Nina Simone cut the greatest version of “I Put a Spell on You,” and regardless of how Cave and the Boys Next Door picked up on the song in the first place, whether the Screaming Jay Hawkins’ original version or Creedence Clearwater Revival’s version or the Arthur Brown version, by 1984 they had heard Nina Simone singing it, and Cave reintroduced the song to his solo set, as an encore no less. This was highly significant, of course, as a wry comment on his relationship with his audience (“like hypnotising chickens,” as Iggy once put it), as well as a sort of career bookend, but perhaps no more significant than the two other new covers he introduced: Leonard Cohen’s “Avalanche,” which would come to open the solo Cave debut, From Her to Eternity; and “In the Ghetto,” the 1969 wide-screen weepy by Elvis Presley. When he soon came to do Kicking Against the Pricks, his covers album, Cave proffered only a couple of songs from his deepest past (the Velvet Underground’s “All Tomorrow’s Parties” and Alex Harvey’s “The Hammer Song”). Most of it was made up of the newer influences that sort of undermined the latter-day Birthday Party, and most of that was folk and blues and country. Leadbelly, Johnny Cash. This was perhaps less a smart move on Cave’s part than just the survival instinct of a true artist: If he was to grow, he had to dig deeper. In other words, if you’re gonna rip stuff off, you just wanna make sure it’s the best. The masters. The roots. The standards. Cave went back to this deepest well to find food for the monster his music had become. And as much as any artist continues to evolve, absorb new influences, this was like a final building block. But nothing Nick Cave has done subsequently hasn’t been underlined by the sort of values he learnt somewhere between the Big One in 1976/’77 and the Birthday Party’s broader ‘arrival’ in England in 1981. Which is, a fierce sense of independence both commercially and creatively. Which was what enabled Cave to so largely swim against the tide, as he did in the 1980s, before breaking through in the 90s. Reflecting in 2007 on the impact of punk, Mick Harvey said, “It was fantastic for Nick and I to have that touchstone as we wobbled through the 80s.” (17) Now Nick Cave could really set to mastering his craft. When I asked him in Australia in the winter of 1983, with the Birthday Party on the verge of its final implosion, Would you agree that love is a central Birthday Party theme? he seemed almost taken aback, bemused by the question. “It worries me that every song I write seems to be about love,” he said. “I mean, it’s not only central, we just harp on it continuously, and the fact that people don’t understand that shows that either we’re not expressing ourselves properly, or that they don’t feel the same things that we do about it, or that they’re… just… thick.” (18) SOURCES Robert Brokenmouth, Nick Cave: The Birthday Party and Other Epic Adventures (London, 1996) Amy Hanson, Kicking Against the Pricks: An Armchair Guide to Nick Cave (London, 2005) Ian Johsnton, Bad Seed: The Biography of Nick Cave (London, 1995) Nick Cave Collector’s Hell, http://home.claranet.nl/users/maes/cave/ Stranger in a Strange Land, Dutch VPRO TV documentary, 1987 Clinton Walker (ed.), Inner City Sound: Punk/Post-Punk Music in Australia (Sydney, 1981/Portland, 2005) Clinton Walker (ed.), The Next Thing: Contemporary Australian Rock (Sydney, 1984) Clinton Walker, Stranded: The Secret History of Australian Independent Music (Sydney, 1996) FOOTNOTES 1. Interview with Nick Cave, in Stranger in a Strange Land (Dutch VPRO TV documentary, 1987), by Bram van Splunteren 2. Interview with Nick Cave, Lindsay Baker, ‘Feelings are a Bourgeois Luxury’, in Guardian Unlimited (on-line, February 1, 2003) 3. Bob Dylan in Chronicles (New York, 2005) 4. Interview with Mick Harvey, in Clinton Walker, Stranded: The Secret History of Australian Independent Music (Sydney, 1996) 5. Ian Johnston in Bad Seed: The Biography of Nick Cave (London, 1995) 6. Amy Hanson in Kicking Against the Pricks: An Armchair Guide to Nick Cave (London, 2005) 7. Interview with Mick Harvey, in Stranded 8. Interview with Nick Cave, in Stranger in a Strange Land 9. Interview with Nick Cave, in Long Way to the Top (Australian ABC TV documentary, 2001) 10. Interview with Nick Cave, in Stranger in a Strange Land 11. Clinton Walker in Stranded 12. Ibid. 13. Ibid. 14. Interview with Nick Cave, in Stranded |