'l' stands for liner notes

|

You can go here to the Domino Records' site to see more details on 'G' Stands for Go Betweens, but since this lavishly-produced box-set has now sold out and is no longer available, I thought it fair enough to run the set of liner notes I contributed to it, in full and unexpurgated. And then I thought, since I so liked the reminiscence my friend and neighbour Peter Milton Walsh also contributed, why not run it as well as my own piece? side by side, by way of a sort of a compare/contrast thing. And so given Peter's good graces, you can see two pretty different takes on the first five years:

|

|

CW

Singles were the thing. During the great late 70s cultural revolution, it was all about 45s. This wasn’t just a reaction against the overblown double-album syndrome that so infected rock in the mid-70s – part of what made it so ripe for the picking – it was the thing an upstart new band could do: Put down a couple of songs (when those might have been the only couple they could play, if ‘play’ isn’t too loaded a term), press up a couple of hundred copies, and get them out there. |

PMW

1978 “I just want some affection.” from a 1978 notebook: Ran through “Who are the mystery girls?” with R & G. Toowong lounge room, Thursday afternoon, tea & biscuits. Could be first time the Dolls have been played in such circumstances. |

|

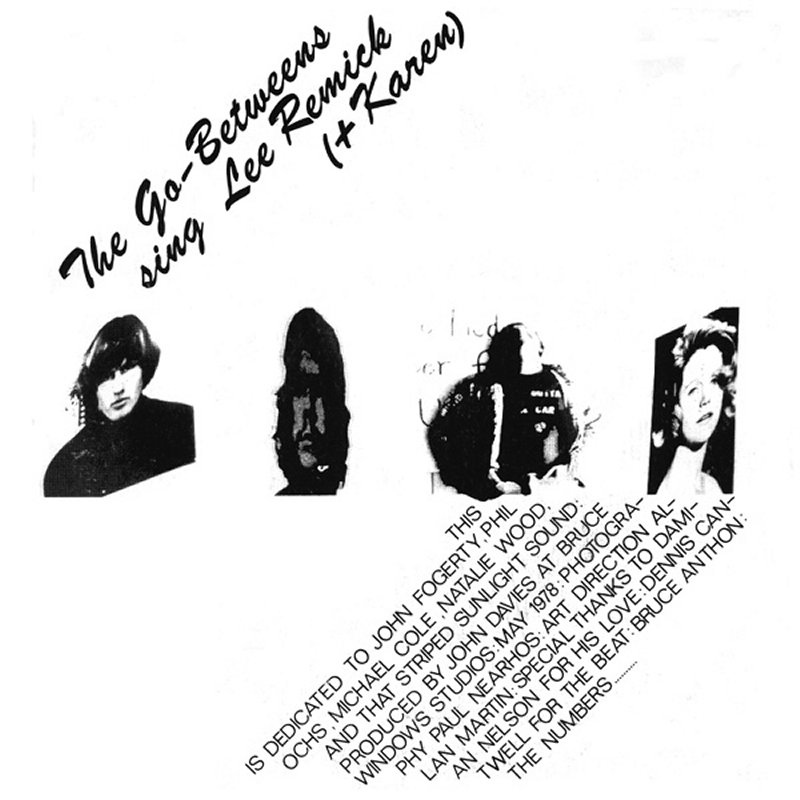

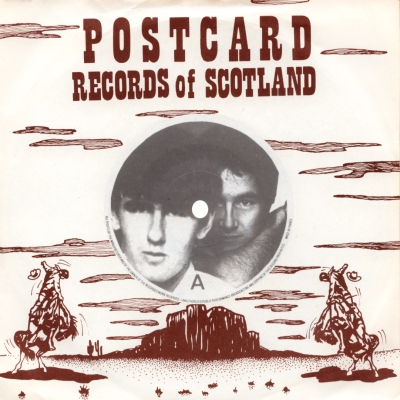

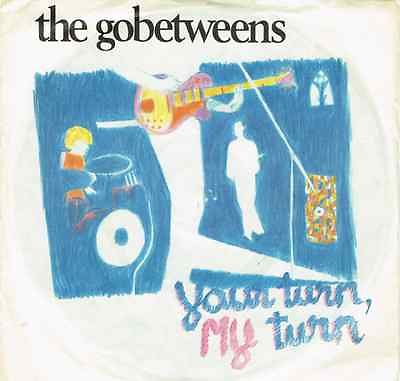

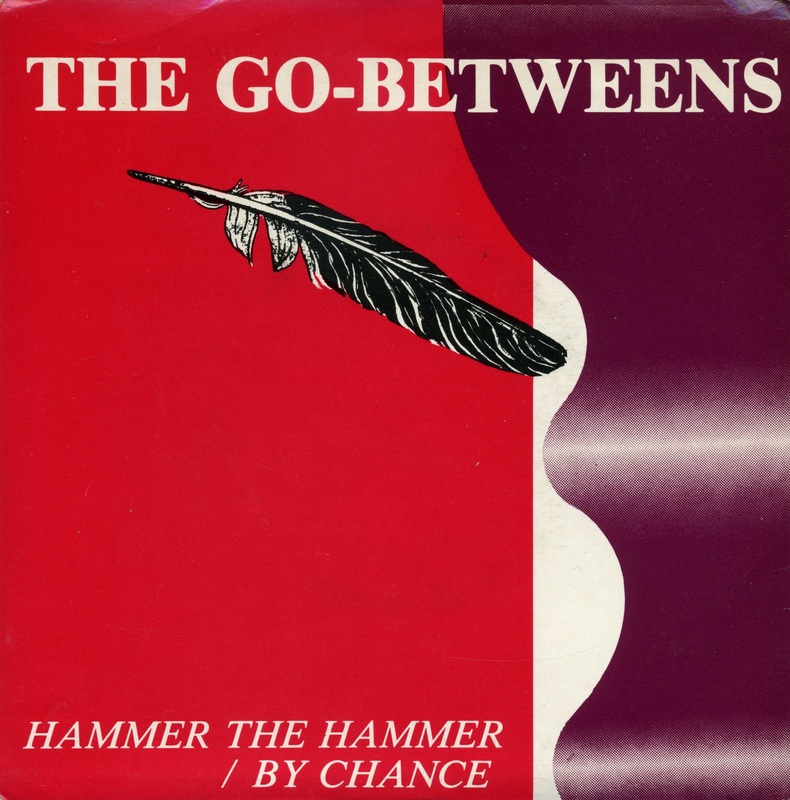

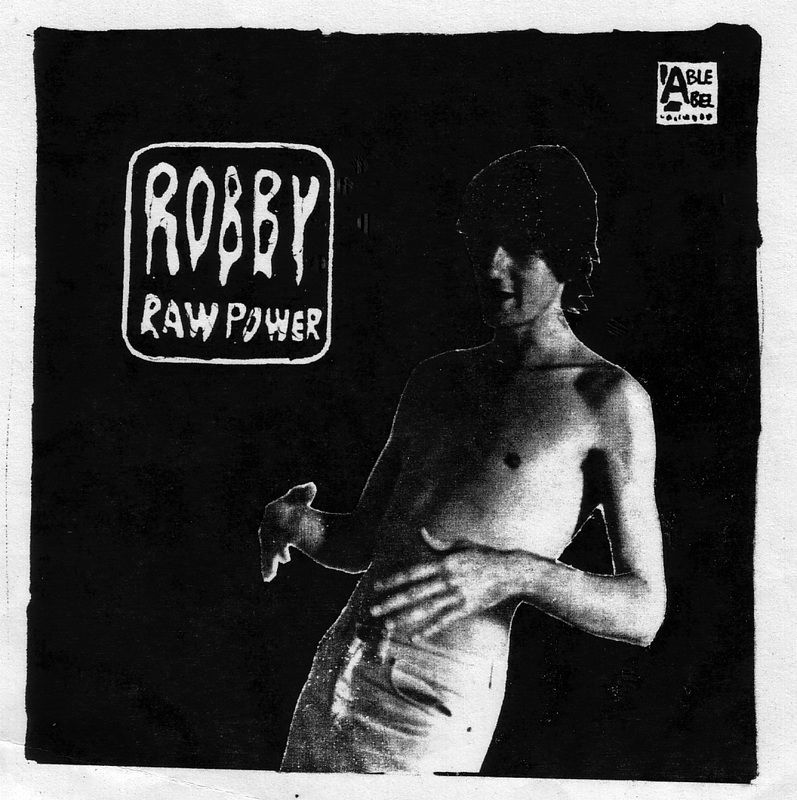

There were albums about, but at a time in 1976 when the only new LPs that seemed to matter were the debuts by Patti Smith, the Ramones, Blondie and the Modern Lovers, all the action was on 7”. There was a canon of early pioneers. Out of New York, Television’s “Little Johnny Jewel,” Patti’s “Piss Factory,” Richard Hell’s “Blank Generation;” and there was the first Britpunk releases like the Damned’s “New Rose,” the Sex Pistols’ “Anarchy in the UK,” the Buzzcocks’ Spiral Scratch EP. And of course – and in one way looming larger than any of them – the very local entry in the field, Brisbane band the Saints’ “Stranded.” These were THE new records that I know turned on Robert and Grant as they did me and inculcated them in the DIY spirit that led them to form the GoBetweens, in 1977. I first heard and met Rob and Grant when they made one of their first-ever public appearances, in Brisbane in the first weeks of 1978. It was at Baroona Hall in Spring Hill. I can hardly actually remember and so have to rely on what I wrote about the event a couple of years later in Roadrunner magazine. Brisbane at that time was of course at the height or nadir of hillbilly-dictator Joh Bjelke-Peterson’s police state, and so since he’d driven any semblance of live music out of venues, bands – especially this growing number of new kind of bands with short hair – had to hire halls and put on their own dances, and just hope the Task Force wouldn’t bust them up. And so it was in early ’78 that the Survivors and the Leftovers, the two top dogs in town since the Saints had left in early ’77, put on a show at Baroona Hall; at which Rob and Grant got up between sets and falteringly played a handful of songs. I was immediately impressed, and not just because they were armed with acoustic guitars, which courageously flew in the face of a generic punk orthodoxy that was already becoming stultifying, but because, simply, there was something just so fresh and original about this unnamed duo. Their songs seemed fantastic. I can’t remember if the gig was truncated by a raid or any violence or not, but certainly, as I soon afterwards moved to Melbourne to live, I filed these two boys away for future reference. In Melbourne, I started writing for rock magazines and was a volunteer announcer on the then-fledgling 3RRR. When only a few months later in the winter of ’78 a single from Brisbane arrived at Missing Link Records, Melbourne’s even bigger hub than Rocking Horse was in Brisbane, it could only have been Rob and Grant; could only be the GoBetweens. I loved the band name too, and I loved “Lee Remick” and “Karen,” and I flogged them both on 3RRR. Even though there was an explosion of independent singles going on, it was still a bit of a struggle, for me, to fill a couple of hours every week, at least in a fashion that met with my exacting standards. I’d love to see a playlist from one of those shows now, it would tell a lot: like, exactly what I was playing. Other DJs on Triple-R were content with the Cars, or Jo-Jo Zep and the Falcons. Not me. Cold Chisel’s debut single “Khe Sanh” came out around the same time as “Lee Remick,” and to me, it might as well have been happening on another planet. (It’s possible to broaden the picture out beyond that too, and say that the year 1978 really belonged to another Brisbane Group, the Bee Gees, with the whole Saturday Night Fever juggernaut – but few of us in the demi-monde even noticed that was happening either...) I played Television, Richard Hell, Talking Heads, Magazine’s “Shot By Both Sides,” PiL, the Subway Sect. It was the cooler-than-thou soundtrack; the Saints’ new posthumous third album Prehistoric Sounds. The Victims’ “Television Addict;” although I confess I resisted “These Boots Are Made for Walking” by the Boys Next Door, even though they were my favorite Melbourne band, until I leapt on their album tracks on the Suicide Records compilation Lethal Weapons. And I played “Lee Remick” and “Karen” to death too. It still stands as one of the great debuts. As Robert and Grant both said many times, in so many words, they were punk insofar as punk meant they could get up with just a couple of songs. “Lee Remick” was an exercise in genre, one of the few the GoBetweens ever attempted, and fair enough for a debut. But even then, it was clearly the work of a budding, precocious talent. This was a group with ideas, a bit of vision, a sense of humor. It was DIY raw, to be sure, but if it was thrashy, it wasn’t beefcake. It was bold and full of chutzpah, it had a sense of narrative with odd or naïf hooks and I found it totally infectious – and it marked the beginning of my long critical championship of and sometimes stormy personal relationship with the GoBetweens as they blossomed in the 80s to become one of the iconic acts of the era. Nothing quite plots the GoBetweens’ emergence, the real birth of a band, than their first five singles: ten tracks, five singles’ worth of A and B-Sides. At a time between 1978 and 1982, when the post-punk/new wave sound was exploding out of the underground, when for a few years every couple of weeks seemed to bring a new single by someone that just sort of rewrote the rulebook, the GoBetweens remarkably released a single per year, one a year every year, for each of those five years. It is a (still) amazing little slice of discographical symmetry, that now almost looks like a set of stepping stones, and an output, to me, that still rivals anything from the same period. These were years of tumultuous change in music. Lots of new wave bands ended up as one hit wonders that didn’t survive to the mid-80s. Who were the enduring acts that came out of this period? If you could hardly count, say, Magazine or the Gang of Four as really enduring. It was DEVO, the B-52s, the Cramps, and the primordial rumblings of acts like the Cure, New Order, Nick Cave, U2 – and the GoBetweens. The opening of “Lee Remick” is explosive in its own modest way. It sounds like a tape edit that comes in hard on a chorus, and it just takes off, like that idea of hitting the ground running, with that chirpy sub-Beach Boys chorus starting everything. It’s amazing to me now that it took me so long to work it out, that one of the models for “Karen” had to be my sister, who worked in the university bookshop and with a raven-black bob looked like a French new wave movie starlet, but that’s another story and one that Robert would doubtless equivocate on anyway. We were all being drawn into a circle whether we knew it then or not. My girlfriend at the time was in a class with Robert, which i didn't know at the time. I’d go to the Schonnell Theatre to see esoteric arty movies and soft porn when Grant was selling ice creams there but I didn’t know him yet either; many of these things I figured out later. When the GoBetweens' entire repertoire probably amounted to no more than half a dozen songs, Rob and Grant hired Brisbane’s Window Studios for three hours one morning, roped in drummer Dennis Cantwell of the Numbers-cum-Riptides, and launched the GoBetweens’ recording career. About a year after “Lee Remick,” “People Say” was released, in mid-1979. It was the third release on the GoBetweens’ Able Label, complete with classic cover art by Grant, and recorded at Sunshine Studios in Brisbane with Tim Mustafa on drums. After “Lee Remick,” Able put out an EP called Sunset Strip by the Numbers (whose line-up then numbered future GoBewteens’ bassist Robert Vickers), and then around the same time as “People Say,” put out an EP called Return of the Hypnotist by the Apartments, the band led by Peter Milton Walsh. I dubbed it all, in a fit of imagination, the Brisbane Sound. Rob and Grant called it the Striped Sunlight Sound. Both terms gained some currency. With names like Vickers and Walsh swirling around, it is the starting point of a mythology or family tree I’ll not go into here because it is otherwise so widely recounted and debated. The GoBetweens were just so well-formed so early. Again very deliberately from the start, Rob and Grant were after something thin, and light. Those terms perhaps sound terrible now. But thin as in as opposed to sludgy, and light as in a warm airiness as opposed to sludgy, or dark or musty. I loved the GoBetweens all the more because just beyond all those standard early late-70s 45s, we shared so much else in common, and I could hear it coming out: the Monkees and Creedence, there’s two to start with, and if you think about singles bands, they’re two of the best. I was right up for the idea of fusing art and bubblegum. I’d read Andy Warhol’s A to B and Back Again. Suffice it to say, “People Say” was again one of my singles of the year. I would have included the Boys Next Door’s “Shivers” on that list too, that was something else I flogged on Triple-R in 1979. “People Say” still sounds good. They got their organ, only it sounded more like a Farfisa than a Hammond, but that was cool too. The songwriting was still developing, but it was already stunning anyway. “People Say”’s flipside “Don’t Let Him Come Back” marked the first-ever appearance of the credit ‘Forster/McLennan’. On the first single the songwriting credits, both sides, went to Rob alone. The A-Side of “People Say” was the same, but “Don’t Let Him Come Back” introduced the conjunction that would become so fabled. Then next thing I know, amid rumors of record deals in the offing, Rob and Grant were going to England. The world was up for grabs for all of us in those days. Where or when to mark the actual deliverance of the GoBetweens? After the first two singles were recorded in Brisbane, the next three would be cut respectively in Glasgow, Sydney and Melbourne. Perhaps it’s possible to break the GoBetweens’ (first) life into a three-act structure that goes something like: the first act was from Rob and Grant getting together up to a point somewhere between getting Lindy in and recording their last single in Australia, which is where this album ends; the second act was the London years; and the third and last act and tragic endgame was returning to Australia and recording 16 Lovers Lane. Rob and Grant always had big dreams. They both loved Brisbane and also hated it, but they had to get out if they wanted to progress as a band, so they went to London toting their acoustic guitars – and found they were in the wrong town at the wrong time. The Pretenders and Gary Numan were hitting the pop charts. In the grimy underground, the former-Boys Next Door/now-Birthday Party were the other Australian band scrabbling around looking for a break, but the GoBetweens and the Birthday Party didn’t know each other yet. Through Rough Trade, where Rob and Grant had a connection to expatriate Queenslanders Ross and Judy Crichton, they were connected to Postcard Records up in Scotland, and so they went to Glasgow to make that particular little slice of history. The GoBetweens found kindred spirits in Postcard and Orange Juice in Glasgow. Using their third drummer in as many singles (Steven Daly from Josef K), “I Need Two Heads/Stop Before You Say It” was always a double-A-Side to me. When it came out in the UK on Postcard, and us handful of fans in Australia bought it on import, it was a striking record, the real beginning of the ‘angularity’ the GoBetweens have ever since been praised and damned for in equal measure. It’s still probably my favorite Postcard single, and there were some good ones in that short catalogue. Rob and Grant then went back to Brisbane and finally completed the line-up for a real band with the recruitment of drummer Lindy Morrison. I went up to Brisbane to visit my family in 1980 and hooked up with the now-trio, to sit in on a rehearsal and do an interview for a story for RAM magazine, for whom I was now writing from my new base in Sydney. In December 1980, the new group flew down to Sydney to play the now-legendary Paris Theatre show with the Birthday Party and Laughing Clowns. I will reiterate this legend because I started it. I always wrote it up as some major momentous event and on reflection, it still seems important. It involved a few key players, notably Ken West and Keith Glass. Keith’s label Missing Link was home to the Birthday Party (who Keith also managed), and Missing Link released the Laughing Clowns’ epochal debut mini-album. Young promoter Ken West in Sydney, who also managed the Laughing Clowns, was putting together the Birthday Party’s first return Australian tour off the back of their first UK-recorded single, “Mr.Clarinet.” I well remember Ken’s reluctance to put the GoBetweens on the bill at the Paris. He was at the time also managing a new young band from Newcastle called Pel Mel, whose debut single “No Word From China” was 2JJ hit (Pel Mel were one of the few new Australian bands that came anywhere near the Sunnyboys in 1980 [INXS didn’t even get a look-in]), and Ken wanted them to open the show. But in the face of a bit of pressure or lobbying not least of all from me – and Keith Glass, who was getting interested in the GoBetweens too – he acquiesced. It was a showcase for the three Australian bands I thought were showing some of the most distinctive possibilities for post-punk music. And there couldn’t have been three more different bands, the Birthday Party with their clattering caterwaul of sex and death, the Clowns with their expansive flights of free jazz-punk, and the GoBetweens with, well, their tinny little set-up that still somehow managed to project enormous character. The GoBetweens were fast, nervous, jittery. Poetic, with Lindy Morrison adding even more angularity. Imagine how boring it would have been had they simply eased into the sloppy strumalong-singalong mode of the some of the folk singers Rob and Grant did admire. Keith Glass licensed the Postcard single for early-’81 release in Australia on Missing Link, with lovely cover art again by Grant, and booked the band into Trafalgar studios in Sydney in April to cut a new single with Birthday Party-producer Tony Cohen. I come into the picture again at this point because I organized a run of three gigs for the band to play in Sydney to help cover their travel costs. All dodgy support spots of course, I was completely clueless really. Ken West wasn’t interested, but at least Roger Grierson, who would go on to much later manage the GoBetweens, slung me a spot opening for the band he then-managed, Tactics. I was working at the time with designer Marjorie Macintosh on my first book Inner City Sound, so I got her to do a tour poster (based on Grant’s single cover) that’s still one of the rarest, loveliest gems among GoBetweens ephemera. The band put down three tracks at Trafalgar, “Your Turn, My Turn,” “World Weary” and “It Could Be Anyone.” Grant’s first sole songwriting credit, “Your Turn, My Turn” became the next – fourth – A-Side, with Robert taking the vocal, and Robert’s “World Weary” taking the B-Side. The single, when it was released by Missing Link in the spring, was the third and last GoBetweens’ sleeve to boast artwork by Grant. Why he stopped doing it is only as much a mystery as to why he even started in the first place. He was a man with perhaps even more talent than any of us ever got to know. Now with a contract to record an album (no shorter than 30 minutes long!) for Missing Link, the group went down to Melbourne during the winter, to cut more tracks with Tony Cohen, at Richmond Recorders. Keith Glass had pre-shopped the album to Rough Trade in London. The mere fact, however, that Send Me a Lullaby was eventually released in two versions, an Australian version on Missing Link and UK version on Rough Trade, might suggest why the group itself always regarded the next album, Before Hollywood, as their real first album. And why the singles plot a clearer path to Before Hollywood… In late 1981, with the album now out in Australia, the band decamped from Brisbane to Melbourne in anticipation of taking the next step on to Britain. Over the summer of 1981/’82, with the Birthday Party back in Melbourne to launch a second return Australian tour and to record a new album for Missing Link – the follow-up to Prayers on Fire that would emerge as Junkyard – a new circle grew. In January 1982, during a break in the Birthday Party’s sessions at Armstrong’s, the GoBetweens recorded their fifth standalone single, “Hammer the Hammer.” It was a song by Grant, about his growing taste for narcotics encouraged by a proximity to the Birthday Party. But the real A-Side, to me, I have to say, was always Robert’s B-Side, “By Chance.” In fact, this version of “By Chance” (and not the later album-track version), is still one of my single favorite GoBetweens’ moments. Missing Link released “Hammer the Hammer” as a parting shot in Australia, and it came out in the UK as the GoBetweens’ first Rough Trade release. By which time (1982), we – that is, the GoBetweens, me, and various other loose Australian musicians and hangers-on – were sharing a big rambling house in Fulham. The next, sixth single, “Cattle and Cane,” was the beginning of a whole new other life, which, not least of all, was more, to me, about albums than singles. All the singles action shifted over to New Romantic/Pop as surely as the old inky music press was superseded by glossies like Smash Hits and The Face. As good as the GoBetweens’ run of 45s in the 80s was, it was the LPs Before Hollywood, Spring Hill Fair, Liberty Belle and Tallulah in which I listened to all the songs in their larger context. Their last album, 16 Lovers Lane, I confess I rarely listened to as a whole. It’s probably my least favorite GoBetweens album, and even as good as “Streets of Your Town” was, I still can’t understand why “Clouds” wasn’t released as a single. It would have been a great last single. |

I left this bit out, but luckily have just remembered —"We’re having snaggies for dinner!” (Robert claps his hands in excitement). It seems pointless to say that I found Robert and Grant—the preposterously boisterous, happy-go-lucky pair of them—completely fresh, particularly in contrast to the bottom of nowhere types I liked to hang around with at the time. Anyone else I knew who was into the New York Dolls was likely—twenty will get you fifty on this—to be lost somewhere in the hurricane of drugs, drink and drama that was then howling through our lives. Robert and Grant had not yet stepped into that particular wind. They were waiting for life to begin. So while we had some differences about how to live, I felt an immediate affinity with them, their jokes and jump-cut chatter and profoundly defamatory gossip. Robert was writing like Pollock painted—grab your material, throw it down fast and move on. Everything that could not be had in life was put into the songs. Songs were a way of wishing. I just want some affection. With Summer in ’78 on its way, I was looking to name the band I'd just gotten together. In the cool gloom of Toowong Music where Grant was “working” (never once, when I’d visited, had the store been troubled by any actual customers), he suggested a name. The Mosquitoes. “You know, Summer's coming. Here come The Mosquitoes—like on Gilligan's Island." Again, Gilligan's Island was not entirely where I was coming from—of course he knew this—so I asked instead what he thought of The Apartments. He said, "Ha! The Apartment. Billy Wilder—the cynical and the romantic. That's perfect for you! Perfect!" I wished I'd said nobody’s perfect—but thanks to Grant, I was sold. It was not the last time he'd help me. The Mosquitoes would anyway have been fatal: I found out later that not only was the name Robert’s idea, but that he’d already used it. I was completely taken with the lyrics of The Sound of Rain, a song I got to record with them, playing guitar. “He walks through the park. Past the butcher shop and the telephone booth where couples talk in the dark." The plainness of the images and language only heightened the poetry for me. The song’s beauty was perhaps slightly qualified by the fact that in the end, the guy wearing— like Marlowe—a trenchcoat and hat in the rain, murders his girlfriend. The track was part of the 8 album contract that had just been signed with Beserkley Records, home of Jonathan Richman. Robert came round to my place, announced the contract, and invited me to join the band. It meant a ticket to England, a contract, money, and playing all the time. Robert had other things in mind. “You know what this means, don't you?”..."Our own hairdressers!" And he clapped his hands. 1980 “the town without trains” A first stop at a bottle shop, followed by a steep climb through the hot December streets of Spring Hill to St. Paul's Terrace where Robert and Lindy, now a couple, lived. Or onto Grant's place in Dahrl Court, just around the corner. These were either/or destinations we’d head to after time in our respective “practice rooms," mine in the Valley, theirs at the foot of the city’s business district. Grant, Robert and Lindy led separate lives outside the band, but came together in the name of the Go-Betweens, a cause that might outlast even love—and they’d stand by one another for it without ever having to think about it or even say it. Wherever we ended up, nights were divided in three: joints, records, drinks. It hadn’t occurred to me before but it was now clear that Robert and Grant had quite different takes on the world. A series of firsts, love and loss, filled both their new songs. Grant was cautiously dipping his toe into the waters of relationships while Robert had dived full fathom five into life with Lindy Morrison. I thought this took took so much courage it was practically showing off. What have you gotten yourself into? Didn’t you just want some affection? The man finally decides to furnish his house and his first choice turns out to be the electric chair. Pre-Lindy, his method with songs had been purely speculative, imagination and observation. Andy's Chest. Like a wedding photographer, he seemed perpetually witness to other people’s hopes and happiness. If there was an intimacy missing from the songs it was because it was missing from his life. Suddenly, the door slams on all that with Lindy and the songs aren’t filtered or scripted anymore, but lived. Lindy Morrison. Her great, upending, tumultuous, machinegun laugh and incessant beating of a rubber practice pad (a rare species of torture) was now everywhere in his life. SHE SPOKE, IF NOT LIVED, EXCLUSIVELY IN CAPSLOCK, a Klieg light in a roomful of 40 watt bulbs. Describing her quickly exhausted all possible weather metaphors. Gales of laughter, gusts of enthusiasm, a storm of personality that broke in every room. For years to come, in so many places and for so many people who adored the Go-Betweens, she would recast perceptions of the band and add to the love people felt for them. This crash course he’d taken had an immediate effect on Robert’s material. A town without trains, he runs to meet you. Rehearsed a first line—it's left him, thank goodness. He was living more instinctively, less in quotation marks. Songs bloomed with all he was discovering. Every temporary madness, illusion, disappointment or ecstasy that love/Lindy threw at him, was now permanently rendered in them. Running through Grant was a strong current of what Soupault described as Blaise Cendrars’ “most stunning gift: enthusiasm”. Hesitantly, I played a new song, No Resistance, to him one night and up from the well of mutedly sung lines he instantly drew one, “the evening visits and stays for years...”. Shaking his head, he told me he loved it. Loved it. That emphatic repetition. Did he sense the line might one day come true for him? His flat in Dahrl Court matched his mind. A bed that was always made, plain white linen. Typewriter, table, magazines in a stack, lines as straight as a ream of paper. Vodka in the freezer, St-Rémy brandy on the shelf, next to it a box of crackers. Nothing but a rind of cheese in the fridge. Books, singles and albums in alphabetic rows. It was austere, clean, and spoke of discipline, a single devotion. Bare, dark wooden floors gave the room great reverb. In the stillness and quiet of night it was a brilliant setting in which to trade songs on acoustic guitar, listen to records, read out loud. Only once did I visit during the day, to return a book Grant had insisted I read. The Horse's Mouth by Joyce Cary. It wasn’t a coincidence that he loved the story of painter Gulley Jimson who, though he knows that a price will have to be paid for it, that so many of the pleasures of ordinary life will be denied him, insists on living for his art. Like Jimson, Grant led an internal life far richer than any external one that was possible to him, and that was the point: if the dream had not yet turned up, he possessed an eternal hopefulness that one day it would. Meanwhile, he would lead the life he wanted to, inside his head. Out of the smoke of memory, his books and records rise and fill the page. Grant had a Blaise Cendrars collection—each of us, of course, convinced we were the only ones who did—Anna Akhmatova, the usual French suspects Apollinaire, Verlaine, Baudelaire (a relentless Francophile, a European son), Adrien Stoutenberg's A Short History Of The Fur Trade, Françoise Hardy's Greatest Hits, Lenny Bruce’s American LP with the black & white cover, every Dylan '66 bootleg that had ever existed, Frank O’Hara, Sylvia Plath, Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano and October Ferry to Gabriola—rarely did you see both—Big Star’s Third, the 1978 vinyl with the two faces on the front, a stack of singles as high as the Eiffel Tower. This was all code, it all seemed important. Even as late as the furnace years of our early Twenties, that ridiculous sense that you were in on a secret that other people didn’t get, still mattered. Why do they call it the narcissism of small differences? Yet no matter how hard we tried to make it feel different, Brisbane still seemed just a long, empty Saturday afternoon kind of town, a place that people died in but did not yet believe in. By then, we were dreaming in the same direction, of other cities, other countries. Our eyes were on the exits. 1982 “on the Atlantic, we’ll all climb.” By ’82, the Go-Betweens had moved to London. I’d moved to New York. At times I felt I had escaped from a burning house—but everything I loved had been left inside. I was living in an illegal basement beneath the Joe Junior diner on the corner of East 16th & Third Avenue. The basement had no fresh air except via the elevator shaft. It was like a dungeon or a ship, heatpipes running across ceiling ticked and clanged like clocks. Steel girders, prefab walls and a concrete floor. Winter was round the corner, and Robert had posted me a pre-release cassette of Before Hollywood from London. I waited till I got home around 2am to listen to it, putting the cassette on in the dark, so it would ring off the cold walls of the room. I immediately fell for it. Disappearances and longing dominated the songs. It was a long goodbye to the country of exile, a kiss blown from a train window. It was not simply despair but, like something by Antonioni, the most beautiful kind of despair. Once they had been like children who spoke precociously well, but with Before Hollywood they suddenly became fluent with the syllables of loss. They would never be the same again. Atget, who photographed Paris as it was racing along in the early 20th century and traces of its past were being swiftly erased, used to write on the back of his prints “will disappear.” The Hollywood Grant and Robert had chosen to write about— the one before the movie industry had even begun, that was still orange groves, barley fields and streetcars was, like Grant’s childhood and Robert’s innocence, a vanished world... “there’s no routine, I’ve never lived like this.” In That Way, Grant sang “there’ll come a time one day, someone will turn and say: It doesn’t have to be that way…” The next day, on a New York postcard, I wrote out Berryman’s The Ball Poem, trying to keep my handwriting neat enough so he could read it, and mailed it to him. For a few years, it stayed on a pinboard in his Hackney room. Up until a certain point in your life, if you think back to times you shared, days that have your friends in them, you believe that they still exist somewhere. That they’re still available to you. That we are all just in different places on the ferris wheel and that when it comes round again, you will see them again. That you’ll take up where you left off. And it’s true, the wheel does come round again—but sometimes, the carriage is empty. |