2: towards a canon

|

Writing about rock in Australia is common enough, it has a long and rich history. But writing about that writing is less so.

Rock itself was so new and moved so fast that it wasn’t really till the 70s it felt it had a history at all, let alone a historiography. The first ‘serious’ rock books started coming out overseas in the late 60s, when the literatures of jazz, blues and folk were already well-developed. It wasn’t till 1978 that Noel McGrath’s Australian Encyclopeadia of Rock and Pop was published, by Outback Press. At that time, the bibliography of Australian rock’n’roll, in book form, you could count on two hands. In the 1960s there were three Australian books published about rock music, after none in the 50s; in the first half of the 70s, there was a drought locally while Australian writers overseas like the late Lillian Roxon, Ritchie Yorke, Richard Neville and Craig McGregor published half a dozen books that place them as pioneers on an international level. In the second half of the 70s, ten books were published locally, most by either Outback Press or Wild & Woolley, both independent publishers grown out of the underground magazine boom of the early 70s. And this was where rock journalism was born, somewhere between the teenyboppers and the counter-culture, between a gossip columnist, news reporter, art critic and gonzo investigator. |

|

In the 80s, after feminism and punk and with deregulation and multi-culturalism, the floodgates opened. There was another boom in independent magazines, and the decade would produce over forty local music books. In the 90s, there would be almost a hundred books published, some of them major best-sellers. In the first decade of this new century, more than double that number again was published, over 200; and since then, so far this decade, even despite the internet-inspired squeeze on the book market, there has been well over 100 rock books published.

These figures I am deriving from a bibliography of Australian rock/popular music writing that I am currently compiling, and which will be published in full at a later date. Meantime, it forms an empirical basis for this more qualitative or analytical, certainly narrative and personal history. Definitions and precedents: Jazz trumpet-player, historian and former Professor of English at Sydney University Bruce Johnson posted online, in the early 2000s, a “Bibliography of Australian Popular Music.” But because this document was designed for use in Popular Music Studies, its bias is academic and indigenous, and these are limitations. One of the great primary sources in popular music, obviously, is or was the popular press and underground press alike (as they used to be called), and to leave those out of a bibliography is to cut off the literature’s roots. It is not enough to rely on library catalogues. So much of the outlaw literature of rock and pop never got so far. And that’s to account for not only around nearly a hundred specialist magazines that have come and gone over the years, but also the writers in the mainstream or general media, and at the other extreme, in fanzines: All this stuff has to be considered. |

|

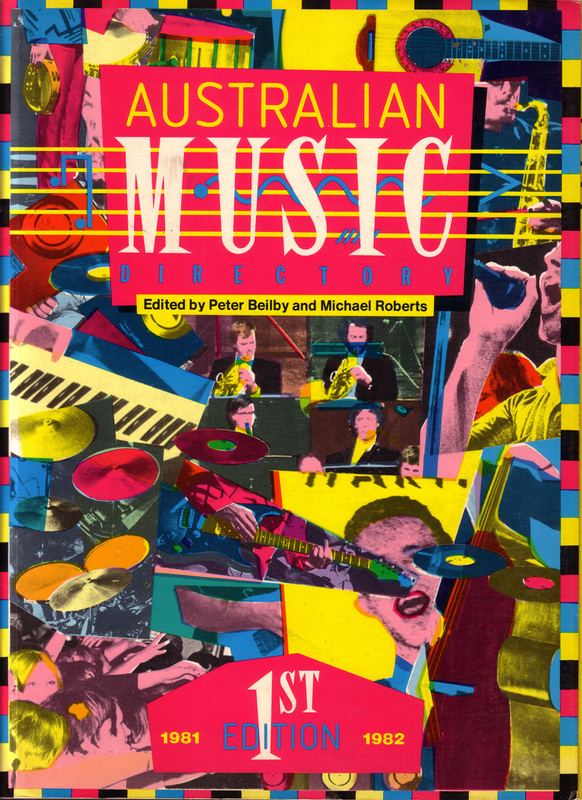

In 1981, a book called The Australian Music Directory was published and it was groundbreaking. Edited by Peter Beilby (of Cinema Papers) and Michael Roberts (then-manager of Jo Jo Zep and Hunters & Collectors), the AMD attempted, for the first time, a one-stop, overall history of Australian rock. This entailed getting in various contributors, myself included, to write a chapter each that added up to a discontinuous narrative. I got the 60s. Which was followed, for example, by Ed Nimmervoll on the 70s. Miranda Brown wrote a chapter called “Idealism, Plagiarism and Greed,” which was a history, the first, of the local rock press, sketching out the story of seminal magazines like Go-Set, Digger, Daily Planet, Rolling Stone, RAM, Juke, Roadrunner and Fast Forward.

|

|

Over the years, those magazines themselves had occasionally had pause to run day-in-the-life-type stories by their writers. But if rock journalism has never been greatly self-reflective, that’s because, as already suggested, it had its work cut out just keeping up with its subject. Besides, any such thinking on the nature of the form would more likely be applied to practically extending it, rather than just theorizing about it.

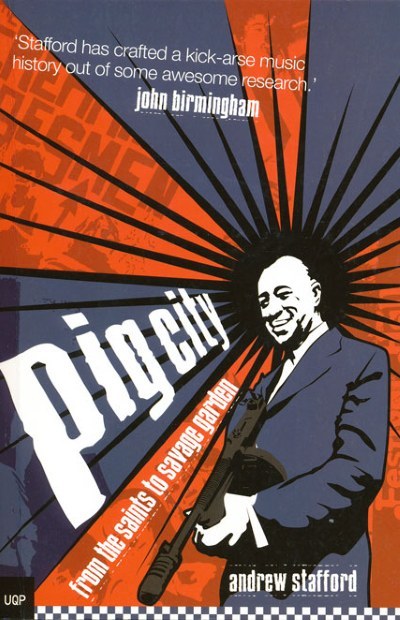

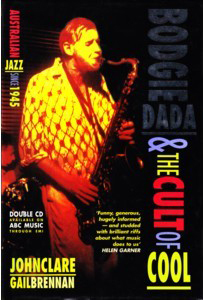

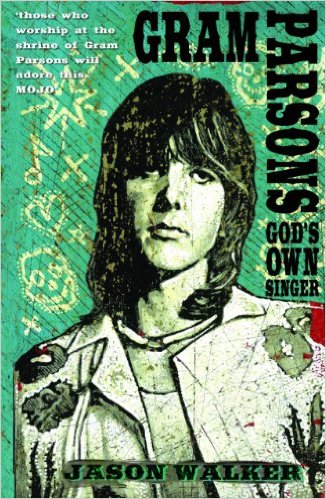

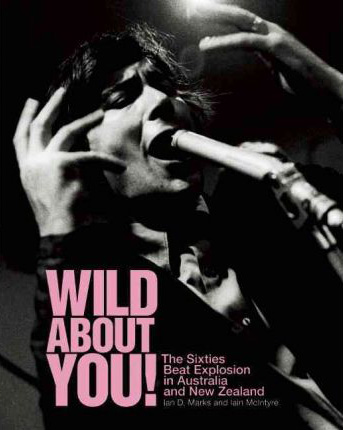

By the early 80s though, even academia was getting a bit interested in rock. Sociologists (like Simon Frith in the UK) were the first, but beyond that, if post-modernism did anything, it was to open the academy up to popular culture. In Australia in 1982, Peter Botsman edited a book called Theoretical Strategies, which contained a chapter co-written by he and Ross Harley called “Between ‘No Payola’ and the ‘Cocktail Set’: Rock’n’Roll Journalism.” But even at a time when virtually no research had been done into Australian rock journalism, Botsman and Harley bypassed the need for any history and in a seemingly classic show of the cultural cringe, averted their gaze overseas: Their article was a paean to the English New Musical Express’s two then-posterboys of post-punk post-modern rock criticism, Ian Penman and Paul Morley. The only local writer mentioned was, umm, me. But it gets worse; even as the Australian scene is taken into account, it gets much worse…. In 1987 – by which time the literature had developed a quite solid foundation (I myself had already published two books by then) – Marcus Breen edited a book called Missing in Action: Australian Popular Music in Perspective. Certainly, it was the first local academic anthology of its type; it included a chapter, written by Breen himself, called “Rock Journalism: Betraying the Impulse.” What was astonishing about this article was its hostility. But then it’s always been easy to kick rock journalism, the lowest of the low. “In Australia,” Breen began, “this beast has a poor history, and an even less likely chance of making history for itself in future.” Proceeding to offer precisely no historiography either, Breen uses random samples from the contemporary press to illustrate his contention that rock journalism is mostly “failure, death and stupidity.” His contempt for rock journalists, “the great pretenders,” is so virulent you can’t help wondering if it was somehow personal, as if he’d had a couple of record reviews knocked back by a hard-nosed editor. But it was fairly typical, certainly back then, of ivory-tower academics who were happy to plunder the hard yards gained by writers and researchers in the field if only to further their own careers in impenetrable post-modern tail-chasing. Since then, even as rock and popular music have become staples of university study (the number of much more recent books grown out of theses is an indication of that), there has been little more attention, scholarly or otherwise, given to the writing about it, save for a scattered few articles by Peter Doyle and Stuart Coupe, and David M. Kent’s PhD thesis on the history of Go-Set, which you can see in full here, along with cover scans of the magazine and many other features. In 2001, ABC radio produced an oral history of Go-Set, produced by Barry McKay and hosted by James Valentine, which you can listen to here; in 2012, in the wake of the death of Andrew McMillan, Jen Jewel Brown wrote an episode of the ABC Radio National program Hindsight about the Australian rock press called “Paper Trail,” which is a fine oral history of magazines like Planet, Digger and RAM, up to the late 70s, and which you can listen to here. It is still common practice in Australian newspapers that when the rock journalist’s comment is called for (usually when someone dies), Glenn A. Baker gets the call. He is the genre’s virtual household name, next to maybe Molly Meldrum. Baker and Molly are yin to yang. Molly is less a classic rock journalist than an all-round pundit, although his contribution to the language generally is doubtless greater than all us other rock journalists put together, if due, like many of our sports commentators, to his very mangulation of it, his legendary malapropisms. But it was Baker, certainly – and this credit should be paid – who espoused a sense of the history of Australian music sooner than almost anyone else. But it’s not enough, obviously, to cite just Meldrum and Baker. The Monthly/Pascall crowd might recognise that some of Australia’s grand dames of letters got their start in the music/counter-culture press: Lilly Brett, Helen Garner, Germaine Greer, Jean Bedford; and also that some of our finest present-day youngish men of letters can claim a similar pedigree: Walkley Award-winners Paul Toohey and Jack Marx both started at RAM in its final days in the late 80s, around the same time that Toby Creswell discovered John Birmingham through Rolling Stone’s campus writing contest. But this is just submitting to the old condescension that a rock journalist could only be any good by outgrowing the genre; that music writing is somehow lesser and only worthy as some sort of juvenile apprenticeship served towards something greater. Plenty of rock journalists themselves have bowed to this pressure. ‘Graduating’ to the legitimacy of film criticism is a very common syndrome. Many leave writing behind altogether - like it was just a means or stepping stone to a more ambitious end - as they go on to jobs in the industry; two major-label managing directors of the 90s/2000s, Ed St.John and John O’Donnell, both got their start at Rolling Stone in the 80s. Some go overseas. But just as many refuse to accept that music writing isn’t a sufficient end in itself. Many burn out. Some – I might include myself in this category – wobble through somehow, continuing to write on the fringes of the local literati. Most go unrecognised outside the small world of our imposed ghetto. But either way there is a legacy, the bibliography, and the bibliography numbers names and titles and places and dates, and I can cast my eyes over it and see the patterns and highlights emerging. Before any books, it is the story of magazines, not only those that Miranda Brown described but so many others too, like Everybody’s, Young Modern, Gas, Oz, Revolution, Spunky, Vox, Virgin Press, Stiletto, B-Side, the Edge, Juice; the list could go on... It is the story of the writing in those magazines. It is also the story of music writers in the daily media, whether career hacks on their way to wherever, or freelance specialists. It is the story of books, of the classic titles of the genre: Glad All Over, Bodgie Dada, Sorry, Pig City, Strict Rules, Hi Fi Days, The Business of Pop, Teen Beat, Lillian Roxon’s Rock Encyclopaedia, Colin Talbot’s Greatest Hits, Pay to Play, Down Under, The Go-Betweens, Blood, Sweat and Beers, Rock Country, Blind Tom, Wild About You, God’s Own Singer… Modesty prevents me from adding some of my own titles to this list, but I’d certainly be willing to pit Inner City Sound, Stranded, Highway to Hell, Buried Country or History is Made at Night up against anything there, and feel confident they’d stand up; feel proud, in fact, that they're as good as it gets. |

|

This is also the story of figures like Philip Frazer, Colin Talbot, Anthony O’Grady and Toby Creswell, who were important as publishers and editors as much as writers. Philip Frazer, in fact, barely wrote anything under his own byline, but as the Czar behind the empire Go-Set built, from Go-Set to the Digger and early Australian Rolling Stone, he fostered a generation of talent including Molly Meldrum, Lilly Brett, Jean Bedford, Jenny Brown, Ed Nimmervoll, Colin Talbot, David Elfick, Stephen MacLean and many others. Talbot was not only our first star gonzo rock reporter but also a partner in Outback Press, which published a number of the early Australian rock books. Anthony O’Grady was the editor and co-founder of RAM (Rock Australian Magazine) and in the second half of the 70s he fostered a whole house style starring the likes of Annie Burton, Andrew McMillan and the two great Brown sisters, Jenny and Miranda. Toby Creswell did something similar at Rolling Stone in the 80s. After Philip Frazer sold the local Stone license to Paul Gardiner in the mid-70s, I myself was the only contributor who served under all four editors between Gardiner and Creswell (with Jane Matheson and Ed St.John in between) and continued to serve, in the 90s, under Kathy Bail. I also traversed RAM editors from O’Grady through Phil Stafford to Paul Toohey at the very end: Which makes me one of the few, I think, to straddle, in a sustained and celbrated fashion, the two great rivals of the Oz rock press, RAM and Rolling Stone. |

|

In nearly twenty years in the trenches, I saw a lot of bylines come and go. Some were undersigned to some great copy, others not so much so. Rock journalism written to be read today and fishwrap tomorrow, can, when it’s good, far outlive this ephemerality.

For example, Frank Brunetti. Frank Brunetti was a mercurial rock writer in the 80s to whom even Robert Forster, no less, paid tribute. In “Darlinghurst Nights,” the GoBetweens’ “Penny Lane”-esque reverie to 80s Sydney on the album Oceans Apart, Forster sings, “Gut-rot cappucino, and gut-rot spaghetti/Gut-rot rock’n’roll, through the eyes of Frank Brunetti.” In the same song Forster also namechecks, daresay, yours truly. As he told the Sydney Morning Herald on his Pascall win, "I've never seen this great division between rock journalists or rock critics and musicians. It always seemed bogus to me.” Indeed, the very bookish GoBetweens’ interplay with writing extends further; for example, the band gave Brisbane writer Nick Earls the tile of his second novel, Bachelor Kisses (1998), and maybe even some of the inspiration for his 2009 novel, The True Story of Butterfish, about a rock star returning to Brisbane to hide out. Brunetti, like Forster after him and Vince Lovegrove and Greg Quill before him, was a musician (or at least a two-fingered keyboardist, with the band the Died Pretty) as well as a writer. But even if Brunetti’s output in magazines like RAM and Vox was irregular to say the least, whenever he did write something it was always worth reading, and even if that work has never looked like resurfacing from the dusty piles of inky old newsprint, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t still read terrifically well. And Brunetti isn’t the only shooting star. He was probably the brightest, but there were others too, who flashed and faded, some of whom did sadly fulfill Marcus Breen’s mean-spirited prophecy, like Annie Burton, Wanda Jamrozic, Mick Geyer or Louise Dickinson, and died too young. I’ll never forget what was just a one-column news item Roger Crossthwaite wrote in the Sydney Telegraph when Bon Scott died in 1980 – that was great rock journalism too. Then there are even more subterranean veterans who kept occasionally doing it into their middle-years. For instance, whenever I saw the byline Mark Demetrius in Rolling Stone, I would read it whatever it is and almost invariably it would be smart and on the money. These unknown footsoldiers need to be remembered along with the stars; without them, in fact, the whole game wouldn’t even exist. |