8: (PULP) FICTION

|

When pop critics started needing university qualifications, it was the beginning of the end. The next phase of the endgame was the internet. The internet has decimated the traditional role of the music writer as a classic gatekeeper in the same way it’s destroying the classic, late-capitalist model of the music industry as a whole. Which is good and bad.

What’s definitely dying is hard copy. Longstanding titles have folded at a rate of knots. Really it’s as if only Rolling Stone and the NME remain, along with, remarkably, Rhythms. All the action has shifted online, where too often it reads too much like advertorial, or is reduced to a one-liner on Twitter. All the rest is history, in books, literally, where the writing is often better – but books, like discs, are dying too. And so the question might remain, has Australia produced a great work of fiction like On the Road say, or John Clellan Holmes’s The Horn, or The Gospel Singer by Harry Crews - a book that captures some essence of the music in our lives? The rock novel itself actually goes back even further than 1960, when Wolf Mankowitz published Expresso Bongo out of the UK, followed by American Harlan Ellison’s Rockabilly. Somehow science fiction and rock stars just seemed to go together, through Mick Farren and Michael Moorcock in the 70s up to the 1990s’ graphic novel Red Rocket 7 by Mike Allred, and Australian Linda Javin’s comic novel Rock’n’Roll Babes from Outer Space (1996). On the Road captured the breathless rush of be-bop, its rhythms and texture. But can rock writing ever approximate the minimalism, the glorious riffing repetition, of, say, the Ramones? In Louis Stone’s Jonah (1911), his larrikin push is always straining to get to the dance hall. The music itself is never quite detailed, but its presence, its lure or effect, is constant, and that presence is much the same as what rock’n’roll would have in the 1960s’ bodgie novels to come. |

|

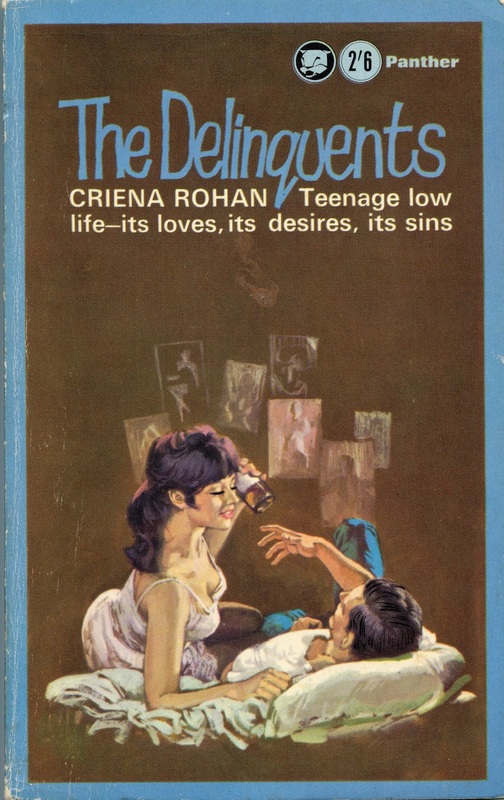

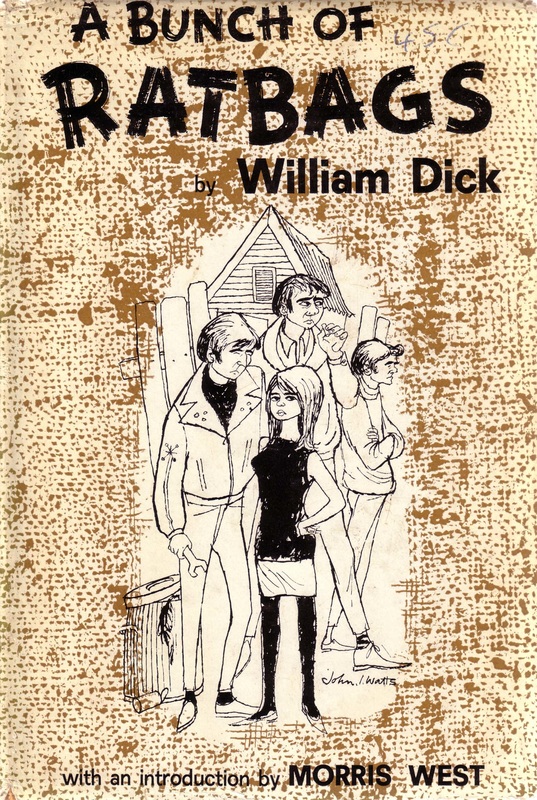

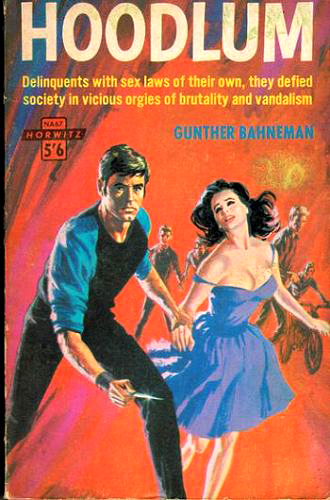

The Australian bodgie novel, of which there was about half a dozen, was a variation on the standard pulp JD novel, in which sex, violence, fast cars and rock’n’roll were all interdependent. Crossing over with the long literary tradition of the prison memoir, the best-remembered Australian bodgie novels, both very autobiographical, were both first published in 1965, William Dick’s A Bunch of Ratbags and Colin Johnson’s Wild Cat Falling. They were preceded though by a couple of Horwitz paperbacks, Ru Pullan’s The Restless Ones, in 1960, and Gunther Bahnemann’s Hoodlum, in ’63, along with Criena Rohan’s The Delinquents in ’62. All these books implicated rock’n’roll in their characters’ youthful waywardness. Sydney pulp-meister Scripts in 1967 published two titles by Carl Ruhan, Wild Beat and The Rebels, and these might be the two best, and the two in which music, significantly, is most essential. Carl Ruhan sounds like he might even be the same person as Ru Pullan; that’s how these writers used to work, churning ’em out under different bylines.

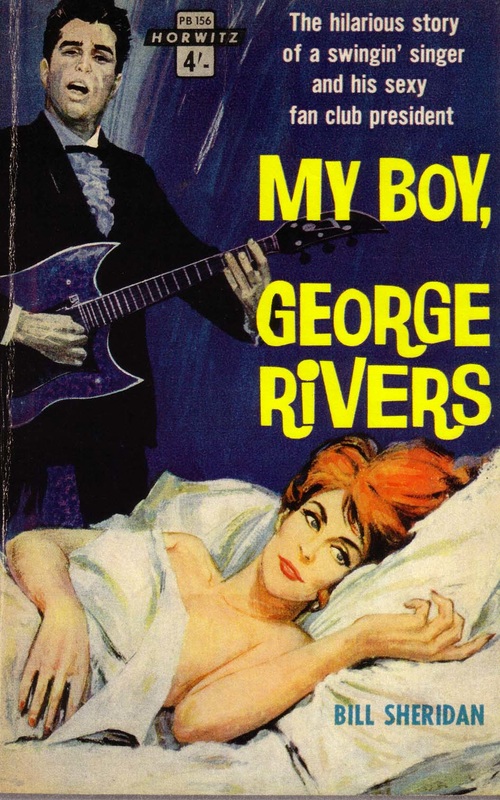

The Rebels is about a Brylcremed bodgie called Bernie who gets caught up in a cycle of crime. Music is his constant companion. He hangs out in Kings Cross at clubs like Michaelangelos and the Dancing Bear, where the house band is the Sheikhs, who play their hit song “Surf City Socrates” - now that’s cool detail! His gang beats up a north shore mod and their exhilaration is matched by the song on the car radio that has that “good solid meaty rock beat.” Wild Beat relocates to Melbourne, the same western suburbs of A Bunch of Ratbags, where a cynical, aging radio DJ called Earl Klaxon is trying to bring peace to the warring gangs, the mods and the sharpies, although the latter moreso fit the description of bodgies. But then Ruhan gets his sub-cultural details confused. “It was the kids who were Klaxon’s bread and butter,” he writes, “and he hated them. Punks.” The first fully rock Australian rock novel was Bill Sheridan’s My Boy George Rivers, from Horwitz in 1963. Like Rockabilly (later retitled Spider Kiss) and Expresso Bongo, it was the story of a gormless young pop singer manipulated by his managers. This was one of the recurring tropes in rock fiction up until Nik Cohn changed the game with I am Still the Greatest Says Johnny Angelo, which instead established the new trope of the gormless young pop singer coming on all messianic and then falling from grace. My Boy George Rivers has some nice detail – like a Gold single called “Rooty Rooty Chip,” whatever that’s supposed to mean – and it prophesies a certain feminist-politicization of the scene, or at least predicts Yoko Ono. |

|

Joanne Joyce published It’s All Right, Ma, I’m Only Sighing through Horwitz in 1968, and as befits a book named after a line from Bob Dylan, it is a coming-of-age story infused with music and the mood of the times, with its soundtrack featuring Jefferson Airplane, the Small Faces, the BGs and the fictional Serpents and Rainbow Tarantula, who headline a love-in at Paddington Town Hall.

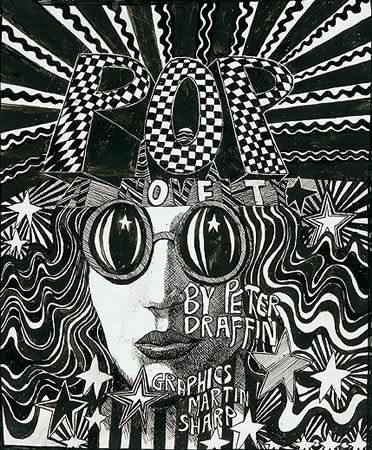

Pete Draffin’s Pop (Scripts, 1967) is a novel, more or less, about a party, or rather ‘happening’, but it’s most notable for its delicious design and illustrations by Martin Sharpe. As an artifact, a period piece, it is a collectible classic. Remember Jack Hoxie (1969), by Jon Cleary, who wrote The Sundowners and You Can’t See Round Corners among other popular novels, is pretty flat. Not that it ever pretends it’s about an overnight young rock star so much as the boy’s father. But if the story of Patrick, whose son Bob is the star in question, was tailored for Cleary’s older readership to be able to relate to – as a gateway to some understanding of – their own children and the music that was so engulfing them at that time, the book betrays Cleary’s own lack of knowledge of the scene in question. Set in the UK, where Cleary lived for much of his career, Patrick is the central character and Bob, with whom he goes on the road as a sort of father-hen, is only an equal secondary character to Bob’s manager, conspicuously a fast-talking Australian (who may or may not have been based on Robert Stigwood), and a young female journalist who becomes the recently-windowed Patrick’s love interest. The plot goes through a race-based bashing of Bob’s black drummer along with the Bobby Kennedy assassination and a crisis of confidence on young Bob’s part, but Cleary’s references to music are unconvincing, and his sketches of the machinations of the pop business are crude. Ricki Francis’s The Groupies (Scripts, 1972) is set at an outdoor rock festival and has as its titular characters a mother and daughter team who vie for the attentions of a rock star who is tiring of his female manager-cum-lover; it could be like the second instalment in a series started by My Boy George Rivers! |

|

Betraying a modicum of working knowledge of the rock industry and concert production, The Sound Mixers, by Eric Scott (1977), tells the story of office romance between a promoter and his Girl Friday as they try to get the biggest band in the world out to tour Australia. It is much the same plot the drives the recent Australian feature film The Night They Called it a Day, except that the film replaces the fictional band Andromeda with the controversial 1973 Australian tour by Frank Sinatra.

So-called literary fiction and music: Christopher Koch’s The Doubleman (1985) was apparently inspired by a Seekers-like folk group, but its eye for musical detail is hazy. Helen Garner’s Monkey Grip (1977), like all her fiction, is very autobiographical, set in 1970s counter-culture Carlton, where drugs, feminism, new theatre and rock’n’roll were all intertwined. Better for an essence of the music scene is her short story "Did He Pay?", which, being about a junkie guitarist (which urban myth has based on Sports-man Martin Armiger), pitch-perfectly captures the lassitude of that particular cocktail of rock and drugs. David Foster’s Plumbum (1983) is apparently “The Ultimate Heavy Metal Experience,” as its subtitle has it, but it’s hardly that, rather a strange picaresque tale, as Foster’s tend to be, about a band getting together, the characters involved, and going on a tour of south-east Asia. I don’t get it. Music was so central to Tim Winton’s Dirt Music (2001) that it was the first Australian novel to come complete with more than just a suggested soundtrack but an actual one on CD, compiled by the author and released by the ABC. ‘Dirt music’ is defined by Winton though one of the book’s characters as “Anythin’ you could play on the verandah. You know, without electricity.” The best books about the Life, and music’s power, tend to be fictionalized memoirs by musicians. The best straight memoirs by Australian musicians tend not, in my experience, to be by rockers. There’s a few in jazz, two by Dick Hughes (father of Christa Hughes, who was always a writer as well as piano-player anyway), and John Sangster’s Looking at the Rafters. Slim Dusty’s couple of books read well too. It shouldn’t be any great surprise though that songwriters especially can adapt to the printed page, and not just in the inevitable lyric collections; many have made the leap to memoir or fiction. Sometimes – as in Nick Cave’s … and the Ass Saw the Angel (1989) and The Death of Bunny Munro (2009) or Stephen Cummings’ Wonderboy (’96), or Damien Lovelock’s What’s For Dinner, Dad? – they have nothing to do with music. More often they do. Along with science fiction, rock’n’roll has always seemed to cross over with crime fiction too, and no less than four musicians have written crime novels, Dave Warner, Peter Doyle, Jane Clifton and Greg Manson. While former “Suburban Boy” Warner can write non-fiction otherwise about sport as well as music (most recently publishing Countdown: The Wonder Years), he has also created a serial ex-rock star detective called Zirco, who solves crimes as in Murder in the Groove (1998). Slide guitarist Peter Doyle can have his PhD dissertation Echo & Reverb: Fabricating Space in Popular Music Recording, 1900-1960 published in the US, and have hillbilly music and rock’n’roll intrinsic to his 90s’ crime trilogy set in 50s’ Sydney, Get Rich Quick/Amaze Your Friends/The Devil’s Jump. The satire is stinging in offbeat fictionalized memoirs like former Underground Lover Vince Giarusso’s Rushall Station (1996) and ockerbilly innovator Peter Lillie’s Monarto: My Brilliant Career in the Australian Music Industry (1999), which is an hilarious sort of prose poem. It’s a shame that former star Go-Set reporter Lilly Brett’s Lola Bensky (2013), a novel about an overweight young rock journalist of that name, is such a silly, shallow and pointless book. Lola, who Brett claims is no alter-ego, is a whining, self-absorbed, musically-illiterate if not racist ditz. I mean, if you’d just seen Jimi Hendrix at Monterey, or had been chatting to Janis Joplin, would you come away talking about yourself, fretting about your weight, or talking about Janis or Jimi? Mind-bogglingly myopic, all Lola Bensky does for Lilly Brett’s legacy as a music writer is destroy it. Typically, the same clueless literati that gave Robert Forster a Pascall Prize thought it was wonderful. Penny Flannagan’s Young Adult novel Sing to Me (1998) delightfully captured the pure joy of music that obviously drove Flannagan in her early 90s’ alt.folk duo Club Hoy. YA could be the new JD with titles like Andy Griffis’s Air Guitar. But if Neil Murray’s Sing for Me, Countryman (1993) lost something for its fictionalization, David Lennon’s Rudeboy Train (2000) gained as much. Perhaps there was more at stake with Murray’s story, as the white schoolteacher who formed the Warumpi Band with his Aboriginal students at Papunya, than David Lennon’s past as the drummer in 80s Sydney ska band the Allniters. Rudeboy Train captures the giddy merry-go-round of gigs, drugs and sex, the bittersweet rite of passage of a young gay musician looking for success, artistic satisfaction and true love. |

|

Non-musician writers getting lost in music? Christos Tsolkias’s Loaded (1995) and Fiona McGregor’s Chemical Palace (2002) are similarly interwoven with drugs, dance music and (gay) sex; the pounding of doof music is so relentless through Chemical Palace that McGregor, fittingly, almost has to shout to be heard above it. And she is actually a one-time sax-player too, in fact the second writer to emerge from unheard-of 80s’ Sydney post-punk band Upside-Down House, the other being Kathleen Stewart, who has extensively published poetry and fiction. (You can read a newspaper item I did on Upside-Down House in 1983 here.)

Peter Skrzynecki’s short story “Rock’n’Roll Heroes” captures note-perfectly the loneliness of the long-distance record collector. It is fiction but true, the bittersweet nostalgia for a long-lost golden age. Are all rock’n’roll fictions necessarily a reverie to the loss of innocence? None other than Robert Forster wrote a terrific piece of fiction in 2006, a short story called “The Coronation of Normie Rowe,” that doubtless weighed well towards his Pascall prize: Re-imagining the recording session of Normie Rowe’s last great hit “It’s Not Easy” in London in 1967, Forster finds the fleeting moment of musical transcendence that so many of us – musicians, fans and writers alike – are in it for. The story hits that elusive high note. Steve Cummings’ Stay Away from Lightning Girl (1999, title courtesy Nancy Sinatra) is the fictionalized memoir of not so much a rock career as its aftermath (much as Nick Earls' subsequent The True Story of Butterfish also was), the story of a washed-up star returning home to Melbourne after several unsuccessful years away. The book is distinguished by its eye for detail, with two hilarious minor characters inspired by Michael Gudinski and Nick Cave respectively. When Cummings’ protagonist Robert Moore is still ambivalent about getting his old band back together to cash in on one of their songs having been revived as an ad jingle, and he protests to a record company executive that at least his solo albums get good reviews, the A&R man, Kellogs, says, sneering, “Rock music died when it attracted critics and was placed in the arts pages along with other dead movements like dance and classical music and literature.” He may be right. But the bibliography continues to expand. And now there is the blogosphere too, or whatever it’s called this week. Everybody is a critic now. Everybody always was, it’s just that now everybody can be heard, theoretically. And so the challenge is to cut through. Much of the talk these days is to do with the on-going relevance of music writing at a time when the music itself is never further away than a cursor-click. But even if that makes redundant what always used to be one of the critic’s functions, as a consumer watchdog, it doesn’t lessen the need for reflection, analysis, insight… and if the present-day writer faces the challenge of having to cut through, and having to get paid, I don’t think that’s much different to what it ever was. |