|

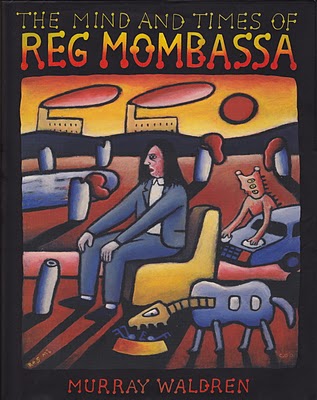

ART, ROCK & REG: Review of The Mind and Times of Reg Mombassa, by Murray Waldren, 2007

THIS PIECE NEVER GOT PUBLISHED. IT WAS COMMISSIONED BY AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MAGAZINE BUT NOT RUN, FOR REASONS NEVER GIVEN, AND CERTAINLY WASN'T PAID FOR. I COULD ONLY PRESUME I'M A BIT TOO IRREVERENT, OR INSUFFICIENTLY FEY, FOR THE ABR One of the most enjoyably abstruse rock books I’ve read in recent times is Michael Bracewell’s Re-make/Re-model, a biography of Roxy Music that ends, after 400 pages, on the mere formation of the band. What the book does is trace the significance of Roxy’s pre-history in the various English art schools that Bryan Ferry and Brian Eno attended during the 1960s. Of course, art school and rock’n’roll have long been likely bedfellows. This now-traditional union has produced not only Roxy Music and Reg Mombassa and his former band Mental As Anything, but other figures as well, like John Lennon and Pete Townshend, and in the later 70s, Malcolm McLaren, the Clash and, in Australia, Nick Cave, Ken West (Cave’s early promoter and the godfather of the Big Day Out) and, daresay – a declaration of interest? – me too! There was much about Re-make/Re-model I could identify with, most notably the characters’ struggles to reconcile the supposedly ‘higher’ aspirations of gallery art with the ‘low’ commercial imperative of pop. There is even more about this book, for obvious reasons, that hits closer to home. I have known Reg Mombassa, aka Chris O’Doherty, for a long time. I first saw Mental As Anything it must have been 1979, when I moved to Sydney to live. During the next decade, Reg and I were both denizens of the same inner-city rock demi-monde, and I crossed paths often with the Mentals. I’ve always liked Reg and admired him and his work, both his art and music. (Another confession: I have an O’Doherty on the wall at home, but it’s by Reg’s brother Pete, a fine painter in his own right.) Yet while I am delighted to note the mere existence of this book, which brings together a rich gallery of Reg’s diverse and voluminous output, it’s hard to suppress a nagging sense of disappointment. The book is beautifully presented, as it should be. The production generally is of an art book standard, equal to anything Miegunyah Press or Craftsman House do, which is sadly rare for the local majors to even attempt these days. It reminds me a bit of those hardcover volumes of Robert Crumb, which I love and I know Reg does too. The colour is sumptuous and the design clean and accessible if not inspired. But beyond the satin-finish surface, the book does feel a bit like a horse designed by a committee. I wonder, then, how it came about. Too often, I think, the backroom machinations of the publishing industry are overlooked in assessing its products. Murray Waldren may be the book’s author, but who is its auteur? In his acknowledgements, Waldren says the book was his agent Lyn Tranter’s idea. Waldren is a seasoned pro and as a Kiwi and Sunday painter himself, seemingly a good fit for the project. At the same time, even given a publisher, a book like this still couldn’t exist without the co-operation of its subject, and though the other dreaded ‘A’-word, ‘authorised’, is never mentioned, Reg himself has obviously exerted a strong influence on the content too. Which is not to deny any of these interested parties’ right to stick their beak in. But whatever the book’s genesis, it’s trying to be a bit of everything for everyone, and while no-one more than Reg knows this is actually possible (it remains one of the Mentals’ remarkable achievements, that almost no-one could dislike them), the holistic result of this lovely doorstopper lacks a little focus and drive, not to mention the wild inventiveness more typical of its subject. It’s not a critical monograph a la Murray Bail’s recently re-issued Fairweather. It’s part art book, part rock biography, part oral history, part family album. As a documentary record complete with discography and artist’s CV, it’s exhaustive to a fault. Ever the gentleman, Reg apologises in his brief personal introduction that “Not every event I have experienced or person I have encountered could be included,” but when you read of, say, his mother’s dental problems, you start to wonder. As great an advocate as I am for the ‘just tell it straight’ school of journalism, Murray Waldren’s text is sometimes pedestrian, and as the pages wear on, it starts to sag. Waldren faces the challenge all rock biographers face: What do you do after the formative early days and the long struggle to the top, when life becomes an endless, tediously repetitive round of touring/recording/touring? To paraphrase Chekov, all bands on the road are alike; it’s what drives them to drink and drugs. For me, it was uncanny, again, to get to the part where Reg, in art school, refuses, as he still does, to make the distinction between high and low brow; and how he was conflicted because he liked the idea of being a radical innovator but also still liked the then-seemingly outmoded idea of figurative painting on canvas; and then how rock’n’roll, the Mentals, started taking over anyway… it was much the same for me and, as Re-make/Re-model shows, Bryan Ferry too. But putting aside the musician formerly known as Captain Beefheart, Don van Vliet, Reg Mombassa is about the only rock star to have achieved genuine standalone success as an artist. In the back half of the book, even as Reg returns to the visual, starting with his graphic design work for Mambo in the late 1980s, there’s too many tall stories from the road goes on forever, which whilst they can be amusing are ultimately frivolous. Waldren repeats the famous story of how early celebrity Reg collector Patrick White thought Reg was wasting his time on design and illustration (the old curmudgeon obviously couldn’t bring himself to even think about rock’n’roll). But, hey, some of us have to work! And it doesn’t make Reg any less, it makes him more. He isn’t just the missing link between Clarice Beckett and Howard Arkley, he also extends a tradition that includes Lindsay, Leunig and Martin Sharp – and none of them could play whammy-bar guitar or write songs the way he does! I can’t help thinking that some of the space devoted to war stories might better have been given over to a deeper analysis and/or contextualisation of Reg’s oeuvre. Nevertheless, I can still enjoy this book immensely, if, in a reversal of the old adage about Playboy magazine, I tend to read it for the pictures. |