|

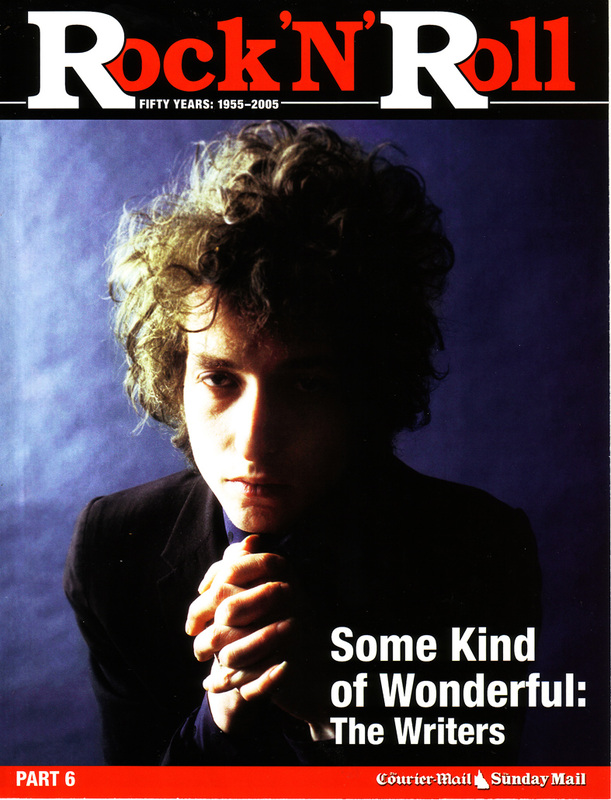

SAGES OF OUR AGE, on songwriting, from Sunday Mail special magazine series celebrating 50 years of rock'n'roll, 2005

|

|

Paul Kelly, one of Australia’s great songwriters, published a collection of his lyrics a few years back called Don’t Start Me Talking. In its preface he wrote, “All the words in this book are connected to music. Often the music is kinder to them than the page. Music forgives them and, if it’s doing its job properly, obscures the weak lines and charges the good ones.” And indeed, on the page, Kelly’s lyrics could sometimes seem thin, or flat. But this is precisely the point he was getting at, and the reason why it’s absurd, say, to call Bob Dylan a poet – because songwriting is about writing songs, not poetry, and lyrics are not meant to be read but heard, sung, as part of a larger musical entity. It’s for the same reason that AC/DC, for example, may say more about Australia than Skyhooks, because even though Skyhooks’ innovation was songs that made specific local references, AC/DC capture the deeper contours, colours and textures of life in this country even as Bon Scott’s lyrics were universal. Paul Kelly’s melodies too can sometimes seem almost second-hand, but when they come together with his words it all adds up to something greater than the sum of its parts. In the mass-media rock’n’roll era, with the decline of religion and of literary forms like poetry, pop songs became our everyday parables, songwriters the sages of the age. You don’t need a weatherman, Bob Dylan rasped, to know which way the wind blows... The modern music industry was born in the late 1800s with the inception of song publishing. Up until the 1950s, despite advances in technology like radio and the (78rpm) gramophone, it was still music publishers (‘Tin Pan Alley’) who largely decided what people heard. But after the second world war, with the innovation of new vinyl records, 45rpm singles and 33rpm LPs, it was the convergence of this technology with the baby boom and rock’n’roll that built the music industry as we understand it today. Before anything else, rock’n’roll was a sound. It was a technological advance - the electric guitar (Fender introduced its famous Stratocaster in 1953). In one way, Elvis was in a tradition the record business already understood, a singing idol like Sinatra or Johnnie Ray. This is where the much-mystified term ‘A&R’ derives from, when record companies appointed men to manage ‘Artist and Repertoire’, which meant they chose the songs that singers recorded. The real paradigm shift in the rise of rock’n’roll was the emergence of singers who sang songs they wrote themselves. In the folksy genres that comprised the roots of rock’n’roll, the idea of the singer-songwriter was fundamental, from delta bluesmen like Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters to honky tonk heroes Jimmie Rodgers and Hank Williams. But when the music business saw it could make money even out of radical new singer-songwriters like Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, Roy Orbison and others, it was transformed. Leiber & Stoller, rock’n’roll’s first great songwriting-production team (whose “Hound Dog” was a ‘race record’ for Big Mama Thornton before Elvis covered it), were New York Jews with as much background in Broadway as R&B. Previously, pop songs were about love – unrequited love, love lost and found (only race records celebrated lust) – but with greatest hits like “Jailhouse Rock,” “Stand by Me” and almost the entire Coasters’ output, Leiber & Stoller introduced satire and social commentary to the Top 40. By the early 60s, the old music business was adapting to the new teen tastes. The Brill Building in New York took over where Tin Pan Alley left off, nurturing writers and producers like Gerry Goffin, Carole King, Burt Bacharach, Neil Sedaka, Phil Spector and Doc Pomus, the names in brackets under so many of the signature 60s songs, whether “Up on the Roof,” “The Locomotion,” “Walk on By,” “I Say a Little Prayer” or “You’ve Lost that Loving Feeling.” At the same time in Detroit, Berry Gordy was building Motown as a new model independent, self-contained hit factory. Motown covered every aspect of writing, publishing, performing, producing, marketing and even choreographing music. By now record companies were overtaking publishers as the main arbiters of taste. Gordy, a songwriter-producer himself, put Smokey Robinson to work as a house writer as well as performer, but Motown’s most successful team was Holland-Dozier-Holland, who would be responsible for more hits than the Beatles, Stones and Beach Boys combined, northern soul classics like “Reach Out (I’ll Be There),” “Heat Wave” and “(You Keep Me) Hanging On.” Then all of a sudden the Beatles and Bob Dylan exploded and it was like the lunatics taking over the asylum. Dylan changed everything, including the Beatles. “What I did to break away,” he wrote in the recent Chronicles, the recent first volume of his autobiography, “was to take simple folk changes and put new imagery and attitude to them, use catchphrases and metaphor combined with a new set of ordinances.” With his integration of influences like Beat poetry and the Bible, Dylan outstripped his image as a protest singer and completely opened up the idea of what a rock or pop song could be. From there, the floodgates were opened. Artists as diverse as, say, Brian Wilson and the Kinks’ Ray Davies were given so much greater license. If nostalgia and lost innocence had long been staple pop themes, Wilson and Davies respectively introduced spirituality and kitchen sink realism to the palette. Yet though there were still many successful backroom tunesmiths - Jimmy Webb even, who came out of left field to write the epic “Macarthur Park,” and gave Glen Campbell a string of hits including “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” and the Vietnam song “Galveston” - and though there would continue to be great pure singing stars whether Aretha, Dusty Springfield or Rod Stewart, after the entrenchment of the LP format it became the worst sin a rock band could commit, to perform ‘non-original’ material. Thus an act like the Monkees was dismissed as manufactured, plastic pop. Yet much of this so-called bubblegum, in the time-honoured tradition of the Brill Building, has survived better than any number of Jefferson Airplane album tracks. The Bee Gees too were commonly derided as a poor man’s Beatles in the 60s, but there are few songwriters to rival one-time Brisbane boy Barry Gibb, whose primal skills are so great he trails only Dylan for the number of cover versions of his songs that have been hits. As the 60s became the 70s, the singer-songwriter signalled the death of the hippy dream and became a byword of the era. Brill Building alumni like Carole King and Neil Diamond heard Dylan and Paul Simon, donned denim and went solo, and became superstars. Erstwhile folkies and country-rockers like Neil Young, James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, Kris Kristofferson, even Tim Buckley, superseded the likes of the late Jim Morrison as American prophets. But if the very term ‘singer-songwriter’ still implies only this archetype – acoustic guitar confessionals – even then there were divergences, like the cinematic Randy Newman or harder-rocking Warren Zevon, both of whom were pianists and comedians of manners; and the eccentric Englishman Elton John, another pianist whose songs harked back to Tin Pan Alley in the way he wrote them with a silent partner, lyricist Bernie Taupin. Today, Neil Young, Leonard Cohen and Elton John, even Tom Waits, remain vital elder statesmen because they’ve always bucked the increasingly odious West Coast soft rock stereotype. Another alternative grew out of English glam rock. Glam had Chinnichap (the Nicky Chinn/Mike Chapman team behind the Sweet, Suzi Quatro and others) the way every era has its finest bubblegum, but in David Bowie it also had a lightning rod like Dylan was in the 60s. Bowie ran two tracks back to back on his coming-out 1971 album Hunky Dory that pointed to a new dichotomy unrelated to sexual ambiguity – “Song for Bob Dylan” and “Queen Bitch.” Well, maybe not entirely unrelated… the latter is an ode to Bowie’s first hero’s polar opposite, Lou Reed, and was an attempt by Bowie to re-align the balance in rock. And indeed, even though Reed, with or without the Velvet Underground, may never have come within miles of a hit, he would ultimately have an impact almost as profound as Dylan. If Dylan was ever, daresay, pastoral or elliptical, surreal, Lou Reed was the coolly detached and very direct voice of urban decay, and he started a line that led, via Bowie, to punk rock. Bowie himself was pure science fiction. It’s easy to forget the storm in a teacup he caused in the 70s when he talked about how he sometimes wrote songs using author William Burroughs’ famous cut-up technique (in which lines, words and phrases would be cut up on pieces of paper and randomly thrown together). Bowie redefined rock songwriting as post-modern and possibly even abstract-expressionist. Led Zeppelin redefined it as a form of sonic storytelling that, like Bowie or AC/DC, transcends the literal. By now the parameters were set. The subterranean punk rock revolution of the late 70s trickled up to become new wave, and no songwriter worth his or her salt could afford to ignore the new visceral minimalism or new electronic technology. But ultimately none of greatly divergent talents that defined the 80s, whether Springsteen or Bono, David Byrne, Morrissey, Madonna, George Michael, Prince or Diane Warren, were ever able or even wanted to abandon narrative. (Diane Who? you may say. Diane Warren is a virtually anonymous [non-performing] songwriter who as the inventor of the power ballad has sold 150 million albums. She is thus generally reviled as the ultimate progenitor of stadium or corporate rock.) In Australia, only the Young dynasty survived a fledgling music industry’s inability to develop bodies of work, going from George Young’s partnership with Harry Vanda in the Easybeats and on Alberts Productions’ acts like John Paul Young, to George’s younger brothers Angus and Malcolm’s pairing with Bon Scott in AC/DC. It wasn’t till the mid-70s that songwriting became a sustainable pursuit in Australia. But as soon as the 1980s, we were exporting or exiling talent that sat comfortably alongside the world’s best, whether Neil Finn, Nick Cave or the Forster-McLennan team behind Brisbane’s GoBetweens. By the 1990s, grunge notwithstanding, it was hip-hop that was having the fullest effect on the way songs were changing. Whether or not the two great Gen X martyrs, Kurt Cobain and Jeff Buckley, did anything to extend the form beyond add a couple more distinctive names to the pantheon, they may, however, remain the last icons. Because as music has expanded it’s also fragmented and shortened its attention span, and so now, if anyone can last longer than fifteen minutes, it’s very unlikely they could be all things to all people. Rap and hip-hop was a whole new language universe. For some, hearing “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and Melle Mel in 1982 was almost more mind-blowing than hearing Little Richard in 1957 or the Stooges in 1973. After Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder came out of Motown’s shadows to politicise sensuality, and Bob Marley came out of Jamaica, self-determination became black music. “It takes a nation of millions to hold us back,” Public Enemy declaimed in 1990 - which is why it took hip-hop so long to break through. But when it did, it was a seachange of vast literary scope. Today, Eminem raps on his new album, “Lets do the math, if I was black, I woulda sold half” (noting that the rhyme and syntax work better on the recording), but his self-deprecation is falsely placed, because genuine gangsta acts now sell as much as he does. And still the love song lives on. In 1999, Nick Cave gave a lecture at the Vienna Poetry Academy called “The Secret Life of the Love Song.” At a time when the world is spinning off its spiritual axis, Cave sees God in the love song, and so to him it is the highest calling. “Occasionally,” he said, “a song comes along that hides behind its disposable, plastic beat a love lyric of truly devastating proportions,” and he cited Kylie Minogue’s 1990 hit “Better the Devil You Know,” one of the supreme creations of Kylie’s former svengalis, much-maligned English bubblegum factory Stock-Aitken-Waterman. “You try saying, ‘I love you’ one more time in a three minute pop song!” Mike Stock laughed when I spoke to him in 2001. “You’ve got about eleven seconds to make your statement at the beginning before everyone goes, What’s this? You’ve got to get your verse organised, set up the story, you’ve got to go through a bridge that links you into the chorus, you’ve got to hit them with a chorus that says ‘I love you’ again and you’ve got to do that three times and get out in three minutes so that everyone knows they’ve had a complete package. It’s a tight framework within which you therefore have to be much more creative to be successful.” “Even the most innocuous of love songs has the potential to hide terrible human truths,” Cave said, as if a “cry out into the yawning void, in anguish and self-loathing, for deliverance.” |