A HOUSE WITHOUT MUSIC

|

This piece was originally written, under the title 'The Vinyl Age', for the book Sociology: Place, Time and Division, which was edited by Peter Beilharz and Trevor Hogan and first published by Oxford University Press in 2006 (BUY it here). The book - with, I'm flattered to say, contributions from some of the finest general writers in the country - is actually a great one-stop-shop (better than any Lonely Planet guide!) to understanding what Australia is today, how we got this way and where we might be going... and the piece itself still serves well, I think, as an introduction to the socio-spiritual place of pop music in post-war Australia:

|

|

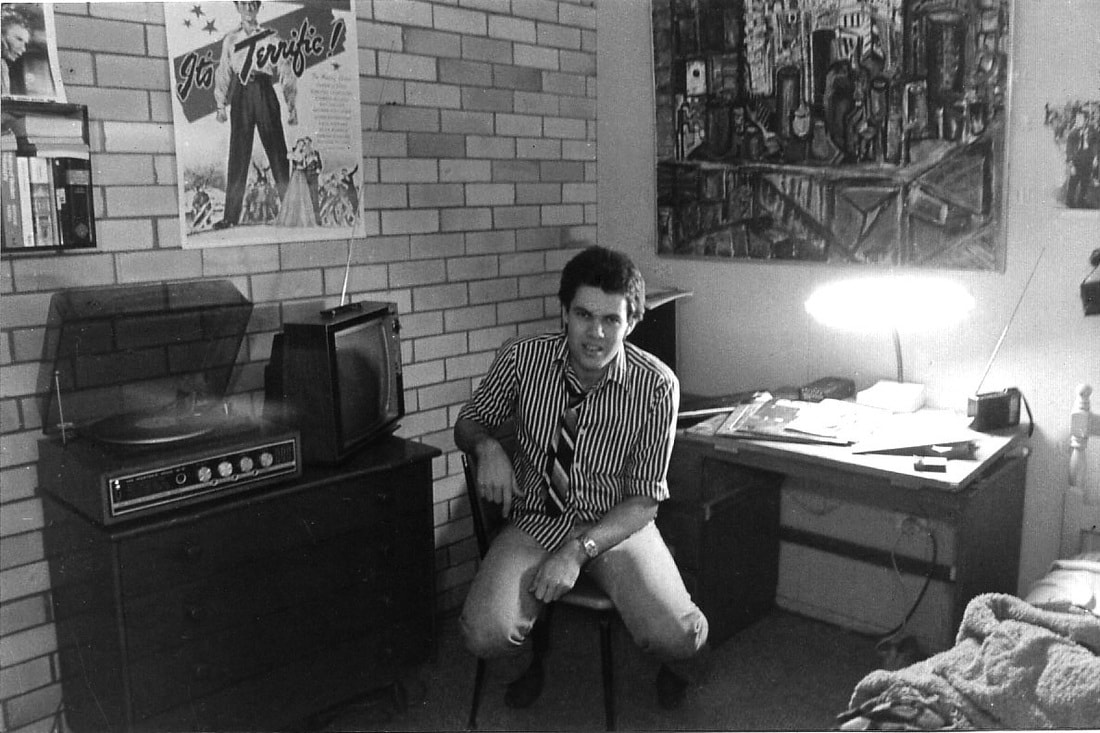

I grew up in a house without music. In suburban Melbourne in the 1960s, we had a spindly-legged (black and white) TV whose blondewood finish matched the polished floorboards and the spindly-legged lounge suite. The décor was modernist but we had no radio or a record player. At the time, the ‘stereogram’ was cutting-edge technology and a furniture centrepiece, a low-set coffin-like box with built-in speakers at both ends and a top that flipped up to reveal a turntable and radio dial. The way music and its place in Australian life has changed can almost be measured by the way its delivery systems, as we now say, have changed.

Neither of my parents seemed to have had much beyond a lapsed bobbysoxer’s interest in crooners and dance bands, and if the car radio was on, it was tuned to sport. There was a certain asceticism about my upbringing that strikes me now as not untypical of old Anglo-Australia. |

|

When I was about ten or eleven, towards the end of the 60s, I got a transistor radio. The trannie was a teen rebel to the grown-up stereogram we didn’t have, and it opened up a whole new world to me. The signal, in my memory, is crackling; it seemed furtive almost and faraway - and doubtless more delicious for it - and music became my church, my ritual and transcendence.

Today, music is the most popular art form. It permeates so many aspects of our everyday lives, and as oldest cliché goes, it is the universal language. It brings people together in a way little else can. |

|

The post-war Twentieth Century was the great explosion of popular culture, if not the golden era of pop then certainly the vinyl era, when so many of the parameters of modern music culture were set. Today, in a post-modern global world, even as digital technology threatens the very foundations on which the music industry has operated since the start of the last century, music is still only just emerging out of the shadows of the vinyl era.

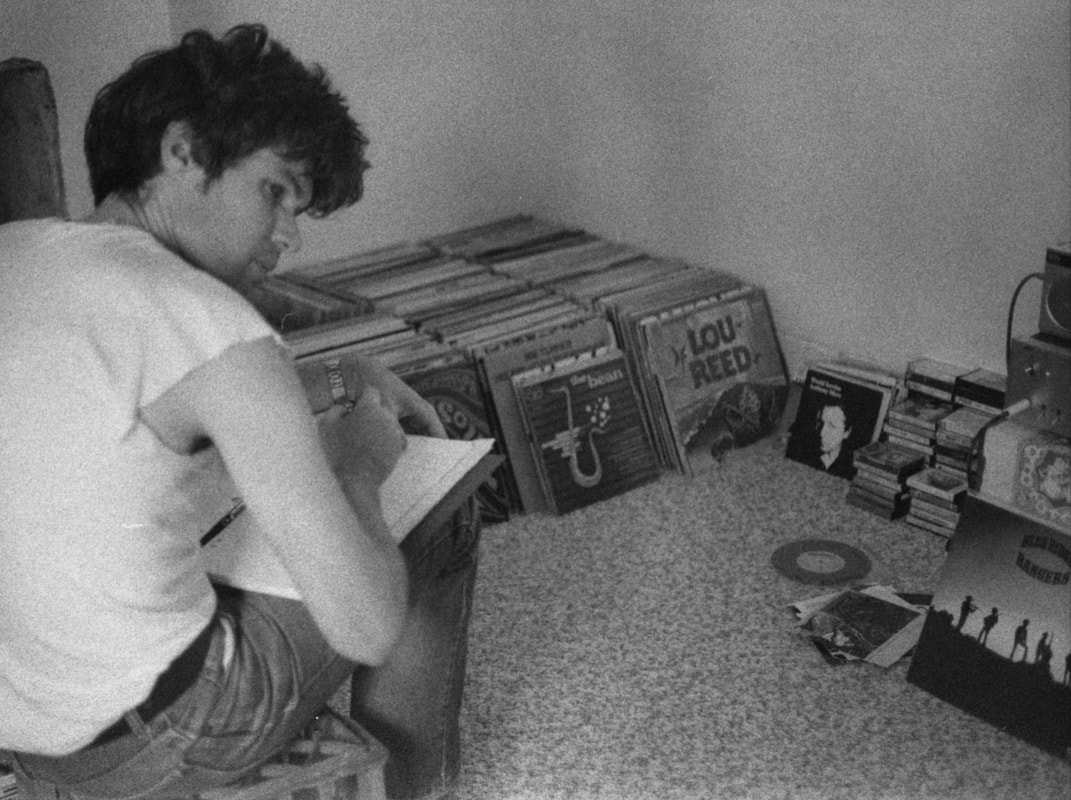

One day, it must have been in 1971, my mother came home with a brand new crappy little plastic record player she must have bought at Indooroopilly Shoppingtown, along with a Kamahl album for herself and a couple of K-Tel/Dynamic Hits-style albums for us kids. My first record was a single, “Spill the Wine,” by Eric Burdon and War, on the old red-and-black Polydor label. I was hooked, and I’m still a vinyl junkie. Music is at once the most elusive and direct art form. Music is not temporal; it exists not in space but time, and it just sort of seeps into life, reverberating on the air and fading away, intangible yet inscrutable and insidious and absolutely undeniable. These are the Uses of Music. It can be wallpaper or a bludgeon, foreground or background, deployed at weddings and funerals alike, to sacred or profane purpose. In his recent book Pig City, Andrew Stafford demonstrates how music in Brisbane during the Bjelke-Petersen era was an implicit political weapon. Art has to be a living, breathing thing. You might listen to music at home or in the car; you might hear it incidentally at the mall, or on the radio, or TV. You might go out to see a band, or hear a DJ. Go to a Greek wedding and you will hear bouzoukis. Go to a pub and you will hear pub rock - or folk, or country, blues… Australia is today but another stop on the international touring circuit, a player on the global music scene whose significance is way out of proportion to our small population. Regardless of whatever canon or traditions in music Australia had developed in 150 years of white settlement up to the Second World War (including the virtual destruction of traditional Aboriginal music), after the end of the war in 1945 everything was transformed anyway. As concertedly multi-cultural as Australia is today, as recently as that time just after the war, we were the second-most English country in the world. Certainly, musically, the middlebrow Anglo-Australian aspiration was to an artistic class system as well, that graded music according to ‘legitimacy’ with the concert hall at the top of the tree, the music hall below the drawing room and our folk roots beneath notice. But with the rise of modern media/technology in the second half of the Twentieth Century, music culture in Australia, as around the world, was amplified and sped-up. Just over fifty years ago, just after the war, most Australian homes had a radio, and many had a piano. Very few had a gramophone; record players and records were an expensive luxury. Barely a decade later, by 1960, the pianos were being replaced by televisions, stereograms and transistor radios. Even before the war, when there was really only one recording company in the country, British-owned EMI, we were growing our own variations on jazz and country music, the latter assuming some of the imperative of our folk bush ballad tradition. But after the war, with not only the arrival here of other major multi-national recording companies like CBS and Philips, but also the founding of local labels like W&G and Festival (now one of the many tentacles of Rupert Murdoch’s world-wide media empire), an Australian record business emerged. The transition was marked by the release of Bill Haley’s breakthrough 1955 hit, “Rock Around the Clock,” which Festival licensed for local release as both a 78rpm 10” shellac disc and a 45rpm 7” vinyl disc. Modern rock-based popular music was born out of this convergence of art, technology and an audience. After radio stations introduced charts to Australia, Slim Dusty was the first local artist to go to Number One, in 1958, with “Pub with No Beer.” The most successful Australian music was emerging vernacular pop, in particular in the country genre (in which, as it also happens, Aboriginal people first found a popular voice.) Pop music marked a great democratisation of culture: anyone could do it, and audiences vote with their feet. To this day, pop styles of music receive none of the government funding that supports, say, classical music, or filmmaking and theatre. Pop’s supposed disposability is one of its great paradoxes and beauties. It’s another cliché, that songs have a life of their own. But some songs survive and endure in a way most don’t. The cliché says that those songs, our modern secular parables, form the soundtrack to our common experience. The 12” 33rpm vinyl LP, capable of holding ideally twelve tracks, about forty minutes of music, was the vehicle by which music became the voice of (baby-boom) youth and (Western) social change. Yet for every list of our supposed greatest hits, like the ‘Songs of the Century’ that APRA (Australian Performing Rights Association) put together in 2001, trumpeting our iconic sonic signposts like “Pub with No Beer” or “Friday on My Mind” or “Cattle and Cane,” we have to remember there’s also plenty of infernal ad jingles we’ll never get out of our heads, and songs that as many people love to hate as love… And still most of us don’t know the words to our national anthem! A couple of years ago I went on holidays with my family to a beach house on the NSW south coast. In that house, in the living room, in the corner, was an old stereo, along with a pile of records. It was an amazing, complete time capsule. The stereo was an HMV8+8, just like I had when I was a teenager in the 70s, and the records stacked next to it, again, were from the same period, as if the whole lot had once belonged to someone (someone quite like myself) and then been put away for a quarter-century before being bought back out again only recently. It occurred to me as I nostalgically spun all these old Rod Stewart and Jethro Tull and T.Rex albums, just how co-related the hardware and the software were. I was reminded of the old piece of Phil Spector lore, that the first tycoon of teen never trusted a track until he’d tested it on mono car radio speakers. It was as if these old records were produced to be heard through this HMV8+8 system, and vice versa. Australian music came of age in the 70s. Rock’n’roll moved into pubs and this new aspect of social life became a virtual rite of passage for young people. The music overcame the cultural cringe, going from “Arkansas Grass” to “Balwyn Calling.” And it overcame its fear of the love song. The romantic love song, one of the basic art forms, was as conspicuously absent from Australian music as the love poem is from our literature. With the first oil crisis of 1974, the post-war economic boom began to contract. Recession set the stage for corporate globalism. Feminism and post-war/post-Vietnam war immigration set the stage for multi-culturalism. In 1977, the whole world was watching as music was changed by two Brisbane bands, the BeeGees and the Saints. The expatriot BeeGees invented disco and the Saints invented punk. Punk was the Blank Generation’s reaction against increasing conservatism, which included the cultural hegemony of the baby boomers. Rock said, Death to Disco; disco was for “chicks, wogs and poofters.” Midnight Oil led ceremonial burnings of disco records. I replaced my old 8+8 with a component system I found as a job lot for maybe $200 in the Trading Post - a Sansui turntable, Marantz amp and these huge Clark speakers. It sounded pretty good back then, especially on the new 12” singles that had grown out of disco, the apogee of vinyl fidelity. |

|

But even then, in the early 80s, it was the beginning of the end for the vinyl era. The Walkman, the ghetto blaster and home video were all instant hits that changed the way we were entertained. The inception of MTV at around the same time took away more than it added. By putting pictures to music, literalising it, rock videos robbed it of its greatest power, its mystique, its openness to interpretation and association. This also pulled it closer towards Hollywood, and further from the grass-roots.

In the 80s Australia was deregulated and multi-culturalised. The pub rock paradigm was challenged and changed by punk and disco. When punk and disco fused through the application of the egalitarian Do-It-Yourself ethic to the technological revolution in electronic musical instruments and recording equipment, techno was born, the biggest formal leap in pop since rock itself. The opening up of the FM band on the radio dial in the same period, plus the rise of the free street press, further wrested power away from the big business interests, the media monopolies and record companies, that hitherto controlled music. The first real alternative charts were launched in 1984. Some people have been mourning the death of pub rock ever since Cold Chisel and Midnight Oil set records in the early 80s that still stand, before RBT came in and fire safety regulations and everything else, but the pub circuit is still alive and well today, it’s just that it’s spread a lot thinner. It is still a ritual that many, many Australians enjoy, going out and bonding with each other and the music through the shared experience of that music. The invention of the CD (by Philips and Sony jointly) in the early 80s was the music industry mating with the fledgling computer industry. The late Kurt Cobain started Nirvana’s career in the late 80s cutting independent singles and ended it in the mid-90s shifting Platinum numbers of CDs. Grunge was perhaps the last instance of pop having great social force. Music can never again be the fulcrum it once was because society now is inexorably fragmented. The first Australian CD, and the first Australian recording to sell over a million copies in Australia alone, was John Farnham’s 1986 album Whispering Jack. It wasn’t long before CD sales were outstripping those of LPs, and by the early 90s, the record companies had given up pressing vinyl. In the 21st Century information age in Australia, music is tribalised, a myriad of genres and niche-markets no longer distinguished along traditional class/race/age/gender or regional lines, but as a result of choices made by the consumer. The Triple-M radio network may still be laughing all the way to the bank with a playlist still rooted in the Golden Age of Cold Chisel, but at the same time, Australia today has some of the best public radio in the world. Music now is returning to a more egalitarian form. Techno is the new folk: Anyone can roll out of bed in the morning, create a track on their computer in the afternoon, and have it out online by sundown. For the producer who regards music as a vocation, this is ideal; for the consumer, the problem is that there’s so much music to choose from, there’s too much. You can listen to anything you want if only you can find it. And still the shapes and colours and textures of most music derive from the vinyl age. Pop has always been cyclic. Hip-hop became textbook post-modernism in the 80s when DJs started cutting and scratching old vinyl records together to create new tracks. The difference now is that pop’s cycles become ever shorter as they turn in on themselves. In 2004, rock is the new rock, so the tag goes. Two Australian bands the Vines and Jet have led this world-wide retro trend to vinyl, valve amps and long hair and flares, and it’s selling by the truckload to tweenies whose parents can play all the riffs on air guitar. Both bands will likely have lifespans as short as the latest Australian Idol spin-off. But in the CD, the music industry created its own monster. If video killed the radio star, digital technology has killed the album, and is threatening the very life of the old music industry. The vinyl LP, with all its limitations and possibilities, was one of the great perfect forms, a golden mean like the sonnet or the still life. As soon as the CD came in, people felt compelled to fill its full 78 minutes of playing time - but all that meant was that we got all the leftover filler we used to be spared by the editing process. CD shuffling further besieged the idea of the album as a stand-alone entity, a suite of songs with an overarching continuity, narrative and themes. Digital downloading and file sharing is making the plastic object itself redundant, as well as defying all the old principles of copyright control. Somewhere between the latest mobile phones and the iPod is the palm-sized internet radio, a portal to the approximately infinite universe of music out there online. DVD, which in rapidly supplanting CD is taking music another step beyond the deadening MTV syndrome, is but a rearguard action designed to wring the last dollar out of the plastic object. Music per se could be lost to multi-streaming and interactivity. In an increasingly isolated and irreligious society, songs trace the currents of our collective unconscious, and when interactivity kills narrative - when we get the stories we want, not the stories we need, which is what myths are – we are spinning further out of the orbit of a spiritual centre. |