very sorry indeed

|

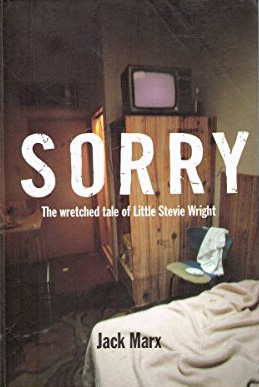

From the Sydney Morning Herald, 1999, a review of Jack Marx's book Sorry, about - nominally - Stevie Wright, former Easybeats' front-man and (truncated) 70s solo star. There is a quote that is routinely pulled out of this review to laud the book - "gonzo journalism at its best;" it was repeated ad infinitum when Little Stevie died at the end of 2015 - but as a cursory read here will show, it is an object lesson in being taken out of context. I bumped into Jack at a party a few years after the review was published, and he told me, "I wanted to kill you when I first read it, but when I read it again recently, I thought it was spot-on!" A few years after that, Marx won a Walkley Award for similarly betraying the trust of a subject - the difference this time being that that subject, Russell Crowe, was trying to take advantage of Marx, so maybe it wasn't so bad. (PS: A few years again after that, Erik Jensen took exactly the same approach, went down into the vortex with his subject, and was lavishly praised for the result, the book Acute Misfortune, about painter Adam Cullen, the difference this time being that unlike Stevie Wright, who was a brilliant artist at his best and a tragic victim of fate, Cullen was a self-indulgent manipulator of minimal talent who didn't deserve to have a(n admittedly well-written) book written about him in the first place.)

|

|

If the publication of not one, not two, but three Michael Hutchence hagiographies hasn’t killed off altogether the idea of Australian rock books, this squalid little tome certainly beats it to a pulp. Rock writing is, of course, the lowest of the low. Jack Marx tells us right at the top of Sorry, a sort of journal of his descent into the maelstrom with a fallen idol, how much he hates pop stars and the pop process. There is something of the zealotry of the recovering here, as indeed Marx himself, before he became a journalist with Kerry Packer’s ‘P-Mags’ like The Picture, was a would-be rock star too. What, then, drove him to complete a seeming kamakaze mission in getting a long-threatened book out of the elusive Stevie Wright, the former front man of 60s Oz rock icons the Easybeats? Like American Camden Joy’s recent The Last Rock Star Book, Sorry is the story of a demented fan’s failure to become his erstwhile hero’s biographer. It is an appropriate note of fin-de-siecle for the genre. The prospect, I have to confess, of wading through yet another sorry saga of heroin-induced desperation and decay didn’t exactly inspire me. Luke Davies, the author of Candy, a novel about love and heroin addiction, may be a lit hit but his poetic lustre, to me, amounts to an unwanted romanticism. Marx declares right at the top, again, how much contempt he has for junkies – and again his zealotry rings of the recovering – but at the same time he has a fascination for low-life (well-drilled as he is in the gutter journalism of the P-Mags, he was also the ghost-writer of the Warren Fellows’ book, The Damage Done), and he seems positively inspired by his bile. His prose, not unlike John Birmingham’s, is faux formal, sometimes hair-shirted but always wry, and Sorry is so racy it can be consumed in a single sitting. It helps biographers, of course, to have an ending, but it doubtless appealed to Marx that Stevie Wright was rather the undead, an addict leading a half-life in the shadow of his own youthful apocalypse. In his prophetic 1967 classic I am Still the Greatest Says Johnny Angelo, Nik Cohn portrayed a fictional rock star in terminal moral decline. Sorry, similarly more fall than rise, is all the more potent for its basis in reality. Of course, it is parlous these days to write biography, or any sort of non-fiction for that matter, without acknowledging an inherent subjectivity. Readers can no longer credit the idea of the unseen, all-knowing objective reporter. But Sorry raises all the old questions of how far is too far? Not that Marx, who is quite upfront about the fact that he changed his name by deed poll some years back, purports to be anything he’s not; nor does he try to pass Sorry off as any sort of definitive truth – in fact, quite the contrary. Like Albert Goldman’s anti-classic Elvis, Sorry has a great enthusiasm for character assassination. But there are differences. Marx is not without some compassion; Stevie Wright, after all, has suffered indignities not of his own making, such as deep-sleep therapy at Chelmsford. But Marx, however misguided, has a personal gripe with Stevie. It is, in fact, one of Sorry’s saving graces, and its most grotesque spectacle, that Marx takes a method approach, going down with Stevie and eventually crucifying himself as well. The way Marx tells it – and he can verify the fact – he doled out masses of his own money to Wright; this is chequebook journalism gone very wrong. According to Marx, Stevie simply stuck the ten grand up his arm. Marx was stupid enough not just to try and buy Wright’s story in the first place, but to hang around like an aimless voyeur way past the point where it was obviously futile to do so. And it’s this display of self-flagellation – Marx is revealed as a dillatantish drug-taker and, in his own words, a possible rapist, but perhaps worst of all, a fool – that strangely gives Sorry its credibility. Obviously Marx got a bit of Wright’s unreliable recollections down on tape along the way, and these have formed the framework for his extrapolations on Wrights’ life. Like Nick Tosches in Hellfire, the Jerry Lee Lewis biography that is a yardstick for all rock writers, Marx gets inside his subject’s head. The irony is, I suspect, that it’s by way of this sort of fancy that Marx has drawn out an essence of his character that to this reader at least rings very true indeed: the power of a novella in non-fiction. Is it ethical? Is it meta-memoir? Or is it fiction? Billy Thorpe has produced two best-sellers so far and no-one seems too concerned for their purported lack of veracity. Surely subjective-memory-based autobiography and authorised hagiography are more pernicious than what’s really gonzo journalism at its best. Perhaps the problem remains, however, that the rock book in Australia was born too late. It was well enough for Nick Tosches to write Hellfire because the literature that surrounded it was already so thorough. Trainspotters will be outraged, but Sorry is likely to be the last word on its subject before the preliminaries have been written. It should be required reading for any deluded innocent still aspiring to either rock or salvation through narcotics. |