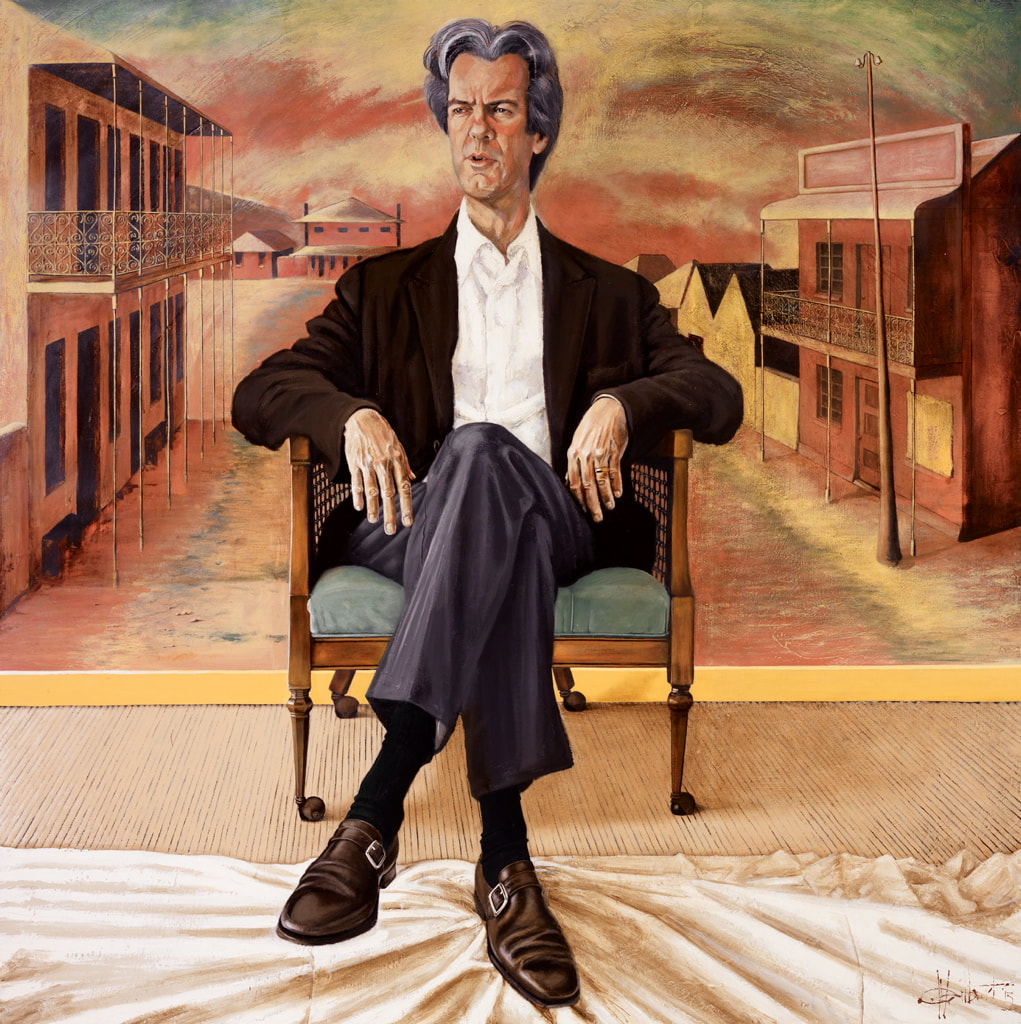

THE DON

|

Don Walker could be a character in one of his own songs. Walker is at home

eating dinner at the same time at the same Kings Cross cafe, every night, surrounded by the sort of faces that populate his songs: A Vietnam veteran haunted by the memories. Ex-cons, hookers, junkies. A once-legendary surfer who the times had washed ashore. Circus acrobats, showgirls. The wide-eyed farmboy who'd been jilted at the altar. Don Walker could be a Tin Pan Alley songsmith, if we lived in another age, or maybe merely a gentleman of leisure. As it is, even though he sometimes might even seem like a man out of time, with his slicked-back hair and expensive tastes in suits, cigars and single-malt whiskies, Don Walker is an enigmatic rock songwriter and perfumer who has just released a second album with his band Catfish, called Ruby. But for all the quality of this album, and its predecessor Unlimited Address, they stand in the shadow of Walker's achievements in the early Eighties, as the driving creative force behind the legendary Cold Chisel. Cold Chisel are the most profusely eulogised rock music phenomenon this country has ever produced, the band that gave us not only present-day working class hero number one Jimmy Barnes, but also Ian Moss, whose 1989 debut solo album Matchbook caused him to sweep the prized ARIA Awards. But the Cold Chisel legacy only begins here, as it also includes a catalogue of classic songs, largely from the pen of Don Walker, which have become virtually part of our vocabulary: Songs like “Choirgirl,” “Saturday Night,” “Khe Sanh,” “Flame Trees,” “Forever Now,” “Cheap Wine,” “My Baby” and “You Got Nothing l Want” are radio staples still. The taciturn Walker has always been touchy about talking about Cold Chisel - after all, he doesn't want to trade solely off his past - but he begged off when asked if he felt it had become an albatross around his neck. "No, no, l have nothing but gratitude to Cold Chisel," he said, “I’d have to sit here for half an hour to list the ways." Walker draws on his panatela and ponders the question; it's a characteristic of the man that he measures his conversation so deliberately that sometimes it's almost painful. "To be honest, l thought that when Cold Chisel broke-up - it's the standard thing for Australian bands - 18 months later, you're forgotten. And so that would mean that ten years of your life, of single-minded dedication, that we all put into it, is just completely down the plughole. Here we are eight years down the track, and it's not, so that's great." Formed in Adelaide in 1974, Cold Chisel broke-up in 1983, the biggest band In the land, and since then, they've consistently sold around 100,00 albums per year (a figure many contemporary bands would envy). East/West, nee Warmers Records, in fact, late last year celebrated the sale of the two millionth Cold Chisel album by re-signing the band, and releasing a 'Best Of' CD, called simply Chisel, which is still sitting near the top of the charts. A commemorative box-set containing all the band's six albums is set for release shortly. Cold Chisel paved the way for the 'Australian Invasion', the success overseas by Australian bands like lNXS and Midnight Oil. They hastened the rise of professionalism in an industry which in the late Seventies was very ad hoc. At the same time, they established a tradition of strong-willed independence without which Midnight oil, for one, would be unthinkable. Chisel were characterised by a veritable wild streak - this was the band, after all, that trashed 5ydney's Regent Theatre stage, after it had cleaned-up in Countdown's annual Awards show, in 1981. But perhaps most importantly, Cold Chisel initiated, and legitimised, thanks to Don Walker, the idea of Australian rock music actually addressing Australian life. Walker was one of the first Australian rock songwriters - thus, songwriters generally - to draw, unashamedly, on his immediate environment, and as such he can only be compared, say, to a David Williamson, as a barometer of his time and place. Without ever descending to the level of kitsch Australiana like a John Williamson, Walker, with an almost journalistic eye, simply documents the world around him - the people, the lives and places he knows. He is seldom a character in his own songs because for an individual as personally guarded as he is, that would be giving too much away. Walker likes his songs to tell a story, to have 'a beginning, middle and end', and Australians have responded to them because they can relate to them. "With this kind of music, popular music, you find yourself getting into dangerous territory when you write anything the average person can't readily identify with," says Walker, betraying none of the pretensions of most rock songwriters, who prefer to consider themselves sages, and prophets. Walker may perhaps never recapture quite the same magic that Cold Chisel had, but Catfish is a band for now which is giving vent to songs by him which still touch on Australian nerves, our recent history. Even despite a cautiousness Walker's conversation belies, and an analytical mind befitting one who gave up a career in science to follow music, as an artist he trusts only his instincts. If he is celebrated as an Australian innovator, he disclaims the achievement, as one born almost of necessity. "The reasons for it were a lot more pragmatic than some theoretical desire to do it. l mean, l was trying to write songs, as an excercise, as a teenager... but in the first year or two of Cold Chisel, we were a covers band, as everybody was in those days. l mean, there were a few bands around in Australia who were doing original music, and they were applauded for it, but it wasn't generally the thing to do. But l sort of figured it was the thing to do, for Cold Chisel. Now, that was by no means a unanimous view, because the reality of it was, in a place like Adelaide, if you tried to do your own music, you just had a lot of trouble getting work. So there was a bit of difficulty within the band as well, they were pretty much into just doing what would work in the Adelaide scene, the covers that would please the crowds. "So to write original stuff and make it palatable, to the guys in the band who were skeptical about it, l had to write stuff that they could relate to very immediately. Which means l had to write about the life we were leading offstage, at that time. And then they could see it. So they did me a favour in a way - if l was writing about politics in China, then, no. But if we were playing for our crowd, and l was putting lyrics in Jim's mouth about what so-and-so did at a party last week, or about our trip to Port Lincoln the week before, then Jim felt comfortable with it, we could do it, and the songs were like an on-going diary. "But then" - Walker allows himself a wry chuckle - "l was always helped a lot by the fact that those people, the places they lived, the lives they led, were pretty colourful, there was no shortage of material..." On the end of a Commonwealth Cadetship, Walker had wound-up in Adelaide in the early Seventies, to work at the Weapons Research Centre in the migrant satellite suburb of Elizabeth. He had grown-up, however, on a farm near Grafton, in northern NSW, after being born in north Queensland, in 1952. His father was an accomplished harmonica player, and the young Walker stuck at piano lessons because "part of the attraction was that we could play songs that dad had played to us, and sometimes he would play along." Those songs were the popular pre-war standards, “Sentimental Journey,” Fats Waller; Walker remembers hearing Elvis early in the piece, and naturally being hit for six. But even then, he hungered for more. "You pick things up along the way," he explained. "By the time l was about 14 or 15, l thought l pretty much had musical theory nailed, Western musical theory. And then, you start to learn, the real stuff. For instance, seeing Duke Ellington in Sydney - he had this young drummer, and I was listening to him, and he was playing a rhythm that could not be written, it was between two things. One time was here" - he signals with his hands - "another time was there, and he was playing somewhere in between, and it was swinging like a paling fence. And l was just sitting there learning this lesson." Although Walker could never consider music as a serious career option, he was drifting inevitably towards it, caught-up in the excitement of the Sixties. "When l got to uni l decided to give up the music and get serious, so l didn’t play in my first year. By the second year, l drifted back into it - my examination results were sort of inversely proportional to my involvement in music." Still, Walker got through the B.Sc. (Physics) course at Armadale, and then headed for Adelaide, and Elizabeth, where he fell-in with the future Cold Chisel. Was he encouraged at all by the mood of optomism of those times, in the Whitlam era, when it seemed like things were possible? "No," he replies matter-of-factly. "Where l was in those days, a working class community, things weren't possible. That question would have a lot more application to someone like Greg Macainish, of the Skyhooks, who really was part of all that. "l just felt, if you're one of the gun songwriters, one of the gun Australian songwriters around, and you want to do it as well as you possibly can - l took it as a responsibility, because nobody else was going to do it, to reflect this place, and the kind of language - l mean, there's a lot of things l love about this place, in particular the language, and the humour. "If l have these skills, and l just used them to write hits, and l don't set myself goals beyond that, l'm not only selling myself short, l'm selling everybody else short. That's not to say you shouldn't try to write hits - if you're not trying to write hits, then you're not trying to reach people - hits just mean you're writing stuff everybody can relate to - but writing hits should not be the only goal.” Walker has never been a writer with any interest in begging the so-called big questions, perhaps because, as a physicist, he would be aware of the macrocosmic implications of the microcosm. He could write a song like “Khe Sanh,” for instance - a sympathetic piece about a Vietnam veteran, long before such sentiments were fashionable - because whilst he'd witnessed the social revolution first hand at university, he was also aware how his old friends back in the bush felt about the war. And he could see both sides. He had an ability to get inside his subjects, even if he was merely an observer of them. Prisoners, for instance, adopted his “Four Walls” as an anthem. Kids in Newcastle, even if they hadn't been involved themselves in riots that Walker documented in “Star Hotel” similarly adopted that song as a rally-call. Most Australians who grew-up listening to rock'n'roll in the Seventies have at least one Cold Chisel song they consider their own. The volatile personal chemistry which was part of what made Cold Chisel great, however, also eventually precipitated its demise. The band failed to crack it in America for similarly temperamental reasons, and in many ways Cold Chisel made all the mistakes, so that a band like INXS wouldn't repeat them. Chisel broke-up amid bitter in-fighting. Jimmy Barnes, the most visible member of the band and its most obviously ambitious, immediately bounced back as a solo artist. Don Walker, however, took an extended sabbatical just so as to get in touch again with the real world. Ian Moss took even longer to re-emerge. Something of a recluse, Walker reserves a bitter contempt for the phoniness and excesses of the rock industry. And certainly, he sees no songs in it. Walker leads a quiet life as a single parent with his ten-year old daughter; he would be much more comfortable at the football than propping up the bar at a gig, let alone putting himself on the hustings. “I tried to figure out, What do l do from here?" he recalled. "Because l was in a situation where I was 31, very successful and retired. People normally get to that stage when they're 65. "The big trap is just to go and do what you've already been doing for the past ten years. So l wanted to get a bit of distance from that, to see if l really wanted to get back into it. Take a bit of time. Look at a few things, a few places. Do a bit of thinking. And not do any thinking at all, just float around, see a bit of the world. "Much to my surprise, songwriting didn't stop. I always thought I was writing songs just because there was a band there that needed them for the next album. I didn't realise until that band broke up, my head kept producing songs. That's when I realised this is something I do not because there's a need for it out there, I do it for my own sanity more than anything else." Amazingly, Walker writes songs not at the piano - and he has a beautiful white grand in the front room of his large inner-Sydney terrace - but in his head. "There's a band playing in my head," he explains, "I close my eyes and this band is playing a song, songs occur to me in the most ridiculous situations. Of course, in that situtation they always sound great. It's like a dream, and the task is to get it down. Usually, you get a few fragments, and from there, that's where you call on craftsmanship. The inspiration is the magical part, but there's also a great pride in craftsmanship." Don Walker is by no means prolific, but he can still toss songs Ian Moss's way. When Cold Chisel broke-up, the schism was largely between Jimmy Barnes and the rest of the band, and Walker and Moss remained friends. Walker wrote the lion's share of the material for Matchbook - although the Number One single “Tucker's Daughter” was a joint effort, written over the phone between Los Angeles and Sydney - and he has contributed songs to Moss's forthcoming, second album. But even though Jimmy Barnes is by now at least on talking terms with Walker and Moss, and even with a large fortune in the offing, a Cold Chisel reunion seems unlikely. While some critics have suggested that Catfish is merely an indulgence Don Walker can afford - and certainly the band isn't setting the charts on fire - the man himself is affronted by the suggestion. Walker initially described Catfish as 'a blues band', if only to establish the idea that it was anything but a conventional rock band. And indeed, even while Catfish boasts a rumbustiously appealing, rootsy sound, it allows Walker to explore possibilities denied in rock, like extended narratives, as he does in songs on Ruby like the title-track, and “The Year That He Was Cool.” Then there's cuts on the album like “El Alamein Blues” (based around the fountain in Kings Cross, a sort of variation on John Brack's famous painting, “Collins St 5pm”), the laugh-in-your-beer country lament “Charleville” and “Johnny's Gone,”which may be nothing more than an excuse for a rockabilly rave-up. Walker is unperturbed by the uphill battle he's aware he faces with Catfish, shrugging, "l've been through it before, and l'll go through it again. “I have this unshakable faith, which has always been borne out," he says, "that with the public in this country at least, if you do good stuff, eventually, it might take time, and a few scams, but eventually you'll win out. "You can't sit back and expect it will happen. You have to make it happen. Sure, there's always some good things that get lost, but sooner or later, with this album or the next one, there's going to be a big breakthrough. And then" - Walker grins hopefully - "you've got a back catalogue as well..." |