VINYL AGE, PART 1: PRE-ROCK

|

For some years before and after the Second World War, EMI had a virtual monopoly on recorded music in Australia. A local recording industry boomed in the 1920s, with international as well as homegrown players entering this brand new field, but the Depression of the 30s killed it off. Ten-inch, 78rpm shellac disks and their players – the hi-tech of the day – were an expensive luxury people could no longer afford. Virtually only EMI survived.

Australia then of course existed in the Commonwealth shadow of Mother England. Twentieth Century popular music was an American invention and by the 30s there was record companies all over the US cutting jazz, blues, country, pop, all these new sorts of music. Hollywood films including musicals travelled outside the continental US all round the world, to Britain, Europe and Australia. American records reached the rest of the world only via foreign licensing arrangements. And so for Empire countries like Australia, that meant via the great patriarch of British recording, the soon-to-be-named EMI conglomerate (made up of such labels as Parlophone [eventual home of the Beatles], HMV [His Master’s Voice] and Regal-Zonophone). EMI in London made licensing deals with the three biggest record companies in America – Columbia (or CBS as it was always known in Australia), RCA and Decca (later MCA, before it was Universal) – meaning that in Australia, American music only filtered down here via EMI in England. And EMI here released only a fraction of the deep catalogues they had the rights to. EMI also relayed to Australian and other Commonwealth territories the output of its arch-rival in the UK, Decca Records, which confusingly was not related to the American Decca label and would in fact be consumed by its expansion into the most lucrative US (as London Records), which was why to prepared to license away to EMI, at least for the meantime, its Commonwealth rights. The story of a music-starved Australia establishing a record business after the war is one of the ending of EMI’s monopoly by challengers arriving from overseas as well as springing up locally. Internationally, after the war, was the real beginning of the modern global music business, with the biggest record companies in their home territories itching to expand in every which way. Although even as the standard image of this history is one of American corporate and cultural imperialism, it was in fact European record companies that started the globalisation process. First, in the late 40s, Britain’s Decca opened its stand-alone operation in America under the London label banner, and then, in the early 1950s, Philips expanded out of its Dutch/German base and opened in America as well as the UK and other Commonwealth territories like Australia, South Africa and South America, where its main rival was the expanding EMI. In 1955, EMI bought up Capitol Records in the US and it was only after that, partly as a consequence of the dominoes it caused to tumble, that then-dominant American labels like RCA and CBS began expanding globally, with WEA following. American tobacco companies, oil companies, soft drink companies, food companies were doing the same thing at the same time. It was a corporate pop-cultural revolution. On the ground in the US, there were new independent labels springing up that would change the music and the business. The first and most powerful, Capitol, was launched out of LA even during the war, and afterwards it hit huge with crooners like Frank Sinatra and Nat King Cole, not to mention paved the way technologically for rock to follow with singer Mary Ford’s partner Les Paul’s innovations with the electric guitar and multi-track recording. Chicago’s Mercury Records was another label that would develop into a virtual new major, especially after linking up with Philips in the early 60s. Beyond that, music was transformed in the 50s by a whole slew of new, regional indies like Atlantic, Speciality, Modern, Imperial, Chess, Liberty, Sun, King, Vee Jay and countless others who tapped into the new electric blues, R&B and hillbilly genres, the strains that would feed into rock’n’roll. EMI in Australia was doubtless selling all the 78s it could press as it was, whether British classical recordings, the schmaltziest of relayed American pop or the most rustic of Australian hillbillies. There were shortages of records and shellac along with everything else in the late 40s. |

|

Charles Higham wrote in the Bulletin in the early 60s: “In 1948, something memorable happened in Sydney: J. Stanley Johnston’s music counters received large stocks of Capitol records – the first overseas consignment since the war – and Stan Kenton and Ella Mae Morse were heard loudly in Johnston’s halls. It was the beginning of the flood. By the early 1950s, ARC and EMI were expanding, more record players were bought…”

Before the war, EMI had heavily pushed local singing stars like Peter Dawson and Gladys Moncrieff, and recorded dance bands bordering on real jazz and even ushered in Australian hillbilly music when, in early 1936, New Zealander Tex Morton cut his first sides for Regal-Zonophone at the old EMI studio at Homebush. Early Australian hillbilly music, arguably Australia’s first vernacular modern pop music form, was fostered almost exclusively by EMI. |

|

During the war, A&R manager Arch Kerr signed Buddy Williams, and after the war one of the first new artists he signed, in January 1946, was Slim Dusty. After the war, EMI even started recording local hot jazz, after George Trevare cut his first sides for Regal-Zonophone in 1944.

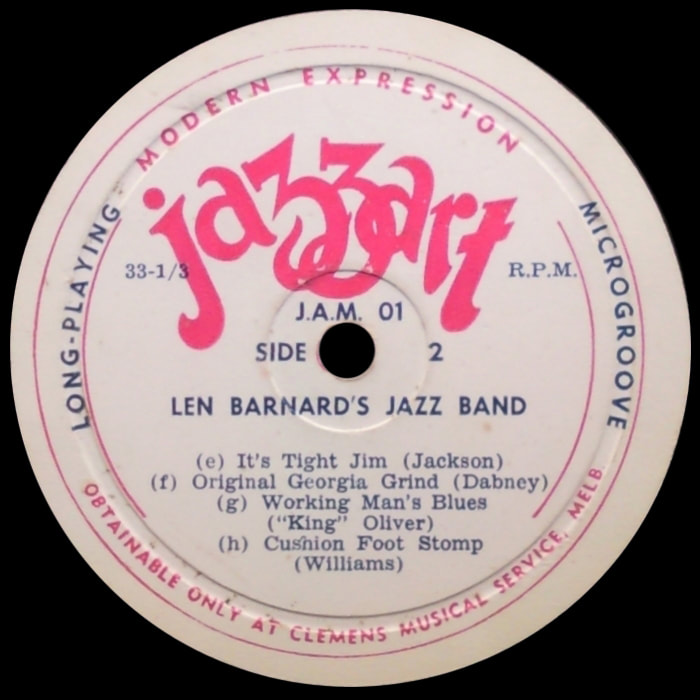

Hot jazz had boomed as dance music in Australia during the war, not least of all thanks to the Yanks who were over here, and so straight after the war, new independent labels sprang up to record it, among them Jazzart, owned by Melbourne nightclub and record shop entrepreneur Bob Clemens, and Wilco, owned by disk-jockey and critic Ron Wills. Graeme Bell started out recording for Wilco and when he moved to EMI would become a major star. Ampersand was another label that released a string of 78s around this time. In 1949, EMI bought the 301 Castlereagh St. site in Sydney where it would set up headquarters and build the famous 301studio. At around the same time also in Sydney, the Australian Record Company, or ARC, was launched. By any other name, ARC had actually started out before the war, as a radio transcription service, pressing acetate disks for broadcast purposes. By 1949 it was ready to branch out as a record company in its own right, with two distinct labels under its umbrella, Rodeo for hillbilly music and Pacific for pop. Jack Argent’s first signing to Rodeo was Reg Lindsay; the label released legendary American producer Ralph Peer’s recordings of Tex Morton, after Morton, a major star, had started out on the Regal-Zonophone label for EMI. |

|

Pacific was run by Sydney boogie-woogie pioneer Les Welch. Welch took as his model the groundbreaking American Capitol label, and set himself the brief, in essence, to produce knockoffs, or covers, of Capitol’s hits. It is a long and noble music business tradition, getting a version of a hot new song out first. It’s not just the Australian cultural cringe, British rock was founded on it too, and the American record companies have always vied to beat each other to this sort of punch. Because Capitol was a new label without international links yet in the late 40s, its records weren’t available in Australia, and so Les Welch could cover its (proven American) hits here and expect much the same result, which he did get. As a producer as well as performer in his own right, Welch’s name was the key one on many, many records that sold many thousands at the time.

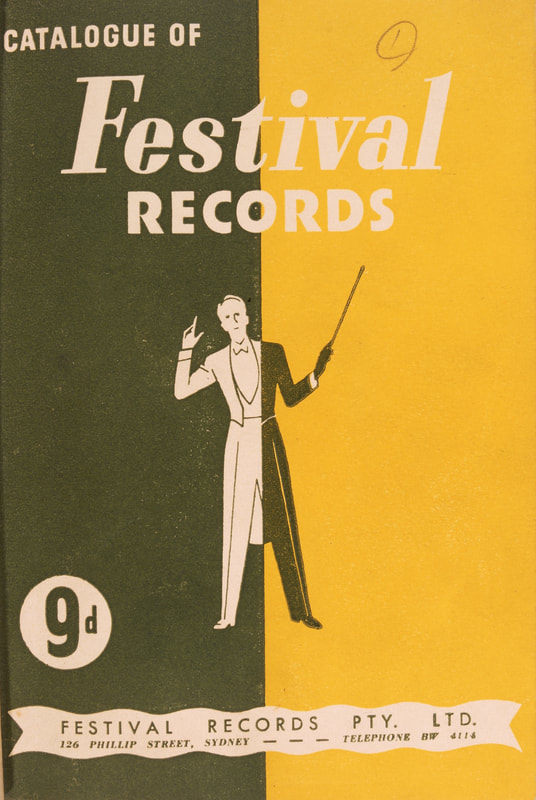

In 1951, ARC made a deal direct with Capitol to lease its recordings for release in Australia. Which, in effect, put Les Welch out of a job. And so, on the rebound, Welch left ARC to form arguably the most important Australian record company of them all, Festival. Getting backing from powerful financiers, Festival opened in an old theatre in Gladesville re-fitted with ten record presses. Its first release, on the Manhattan label, was a 78 by Welch himself, a version of then-current US hit “Meet Mr Callahan,” and it reputedly sold ten thousand copies. One of Festival’s other earliest releases (FM-6), towards the end of 1952, was an album by Welch, a 10” 33rpm ‘microgroove’ vinyl LP called Tempos de Barrelhouse – which is often described as Australia’s first album. But as even a cursory amount of research reveals, the search for the first Australian vinyl record is a parlour game as fraught as our art historians’ attempts to pin down the first oil painting made in this country. |

|

Vinyl was first used to make 78s in the US during the war, when shellac supplies ran out after the fall of Singapore. After the war, the two biggest majors, RCA and CBS (who weren’t just record companies but also broadcasting empires and electrical goods manufacturers), developed the vinyl record: CBS concentrated on the ‘microgroove’ LP, initially a 10” but ultimately a 12” long-player, which was launched in 1948; and RCA fostered the 7” 45rpm single-play, which it launched in ’49. These formats were gradually adopted throughout the world, although the shellac 78 would still take a good decade to fully die (and three-speed record players, born in the early 50s, would persist till well into the 70s).

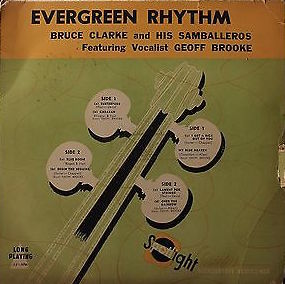

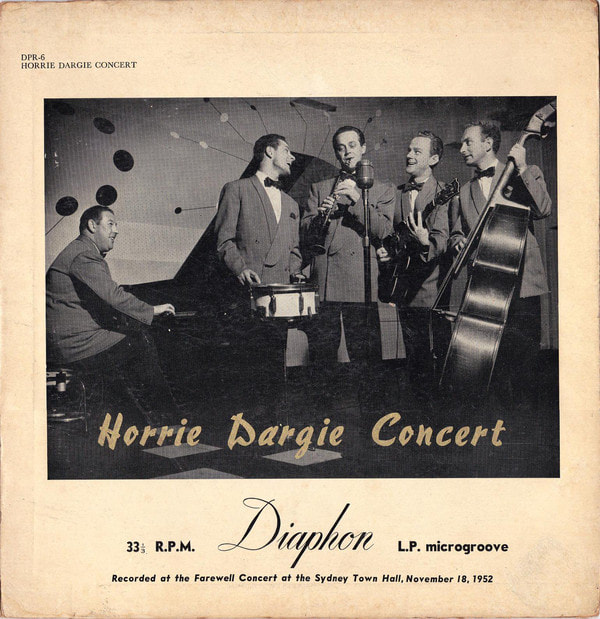

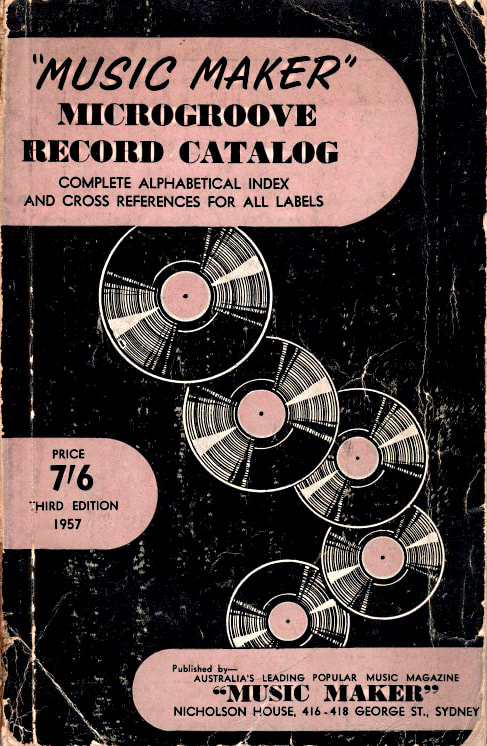

There are plenty of other challengers to Les Welch’s claim on the first Australian vinyl album (the vinyl single would not be launched here for a couple of years yet). By the late 40s, Australia was rife with new, independent record companies, many of which began on 78 and equally pioneered the new microgroove format. In September 1951, Music Maker magazine reported, “Diaphon Scoops Pool with First Australian LP Disc” – a 10” album of the Civic Symphony Orchestra recorded in performance at the Great Hall of Sydney University under the baton of Haydn Beck. Diaphon was one of the new local labels that would go on until the mid-50s to release a string of pioneering albums, and this one was a full year before Tempos de Barrelhouse. Also before Tempos de Barrelhouse, during 1952, were Diaphon’s first pop album, Midnight Melodies, by the Art Ray Quintet, and the first of Melbourne label Spotlight’s fifty 10” albums to follow, guitarist Bruce Clarke and the Samballeros’ Evergeen Rhythm. |

|

In October 1952, Music Maker reported that Jazzart had released the first Australian jazz LP, by Len Barnard’s Band, cost 37/6. Two months after that in December 1952, Plattavox released the album Music for Pleasure, by William Flynn and his Orchestra with vocalist Darryl Stewart: All of which was prior to Tempos de Barrelhouse.

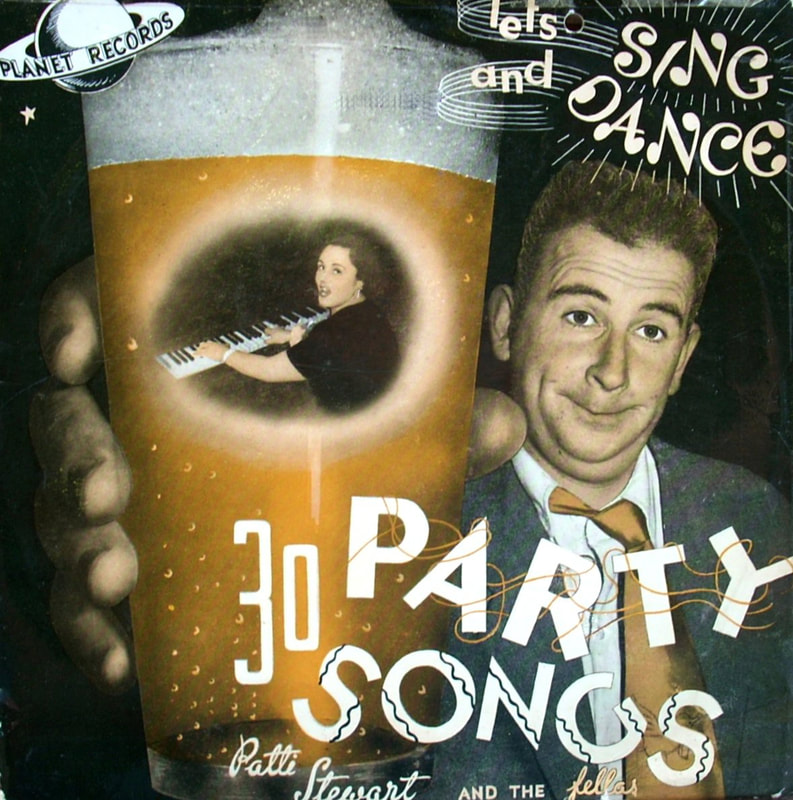

Finally in March 1953, music magazine Tempo reported on Tempos de Barrelhouse, “Welch Waxin’ Wows ’Em: This time Les has put down on disc the first microgroove efforts of any group of Australian musicians.” EMI in Australia was initially sceptical about the new formats and slow on the uptake. ARC, on the other hand, quickly started relaying Capitol album releases. Capitol was one of the pioneers of the LP form, with classic hits like Sinatra’s first title for the label, 1954’s Songs for Young Lovers, sometimes called the first concept album. The LP was obviously tailor-made for longer-form styles like classical music (which was always compromised by the shellac 78’s three minutes a side) and showcast recordings. It also encouraged jazz to be recorded the way it tended to be played live, longer due to improvisation. When EMI in Australia finally got with the program, one of its early album releases, the original Broadway cast recording of South Pacific, was one of Australia’s first hit LPs. Spotlight, Diaphon and Planet were just three of the leading Australian pre-rock independent labels. There were plenty of others. There was Prestophone, Fidelity, Celebrity, Esquire, Tempo, the joint Magnasound/Paramount venture, Radiola (owned by AWA), and Swaggie. Spotlight had a country division called Round-Up. Also in Melbourne, like Spotlight, was Planet, run by Bob ‘King’ Crawford. Planet’s first two releases, in 1951, were two 78s by Allan Rhodes and his Orchestra with singer ‘King’ Crawford himself. When these four cuts were soon compiled onto an EP (Extended Play) called Jump Time, this might have been Australia’s first slice of 45rpm 7” vinyl. |

|

The two Melbourne labels that would survive the 50s though, to become ultimately the most important south of the Murray, were Astor and W&G. Astor was an electrical goods manufacturer that started a record division on the basis of a license deal with new American label Mercury, and it generated almost no local product of its own at first. But it had a distribution network. W&G, on the other hand, an outgrowth of the White & Gillespie plastics business, did nothing but local releases, including distribution of the Diaphon catalogue.

What was EMI’s first local album? Might it be Nine Australian Folk Songs, by Burl Ives? released around 1953. Can this title also be considered the first commercial recording of Australian folk music? Certainly it predates either Diaphon’s Excerpts from Reedy River, the soundtrack of the stage show from ’54, and Wattle Records’ first 10” of Australian songs sung by Briton A. L. ‘Bert’ Loyde. |

|

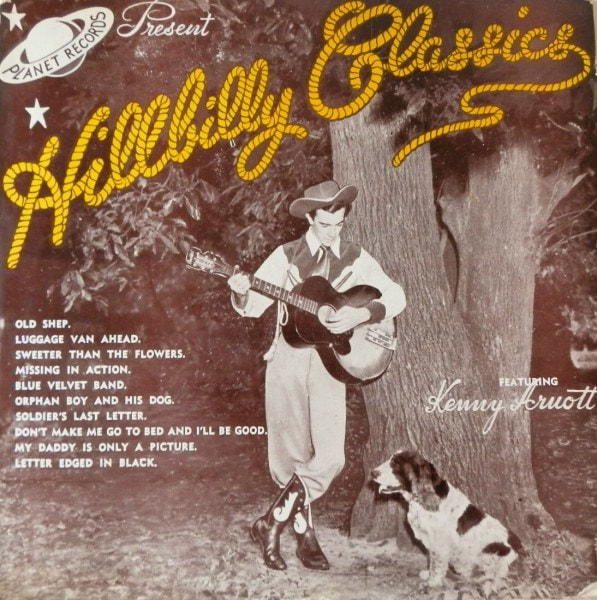

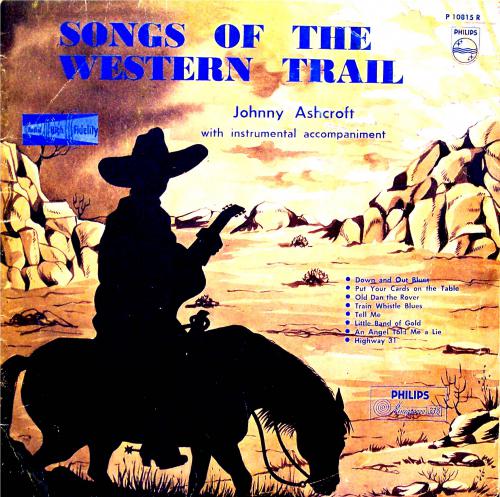

Was our first country LP Planet’s Hilbilly Classics, by Kenny Arnott, or was it the Johnny Ashcroft album on Philips, Songs of the Western Trail? Even Slim Dusty didn’t release an album until 1960. Was Ashcroft’s preceded as the first local album for Philips by piano-accordionist Herbie Marks’s Music for Romance? Philips was the European major that completed the recording industry landscape in Sydney in the early 50s, having set up shop here very quickly after the company was first founded in Holland at the start of the 50s.

Was the first 12” album pressed in Australia the Philips release of 1951’s Ellington Uptown? Was the first Australian 12” album Diaphon’s Evergreens of Rogers and Hart by Wilbur Kentwell, in ’54? |

|

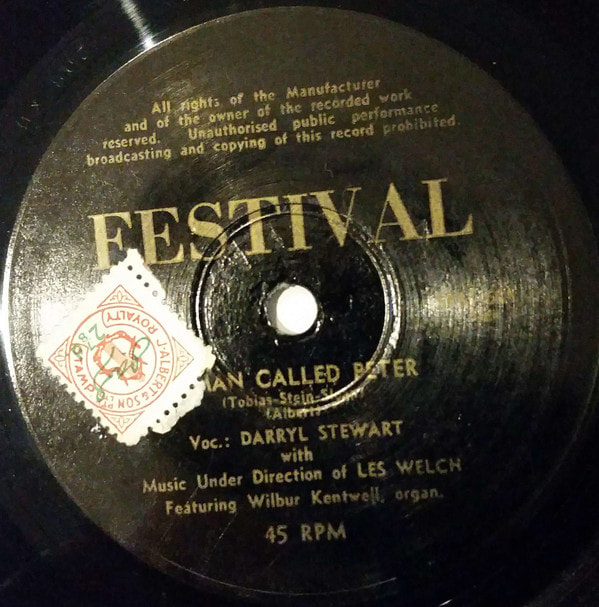

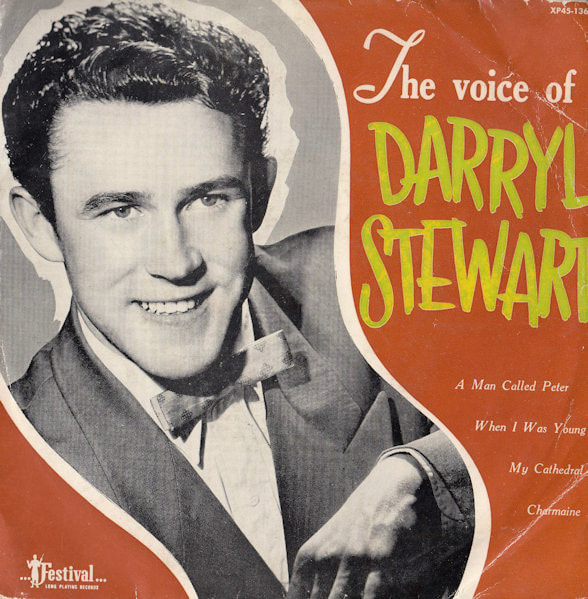

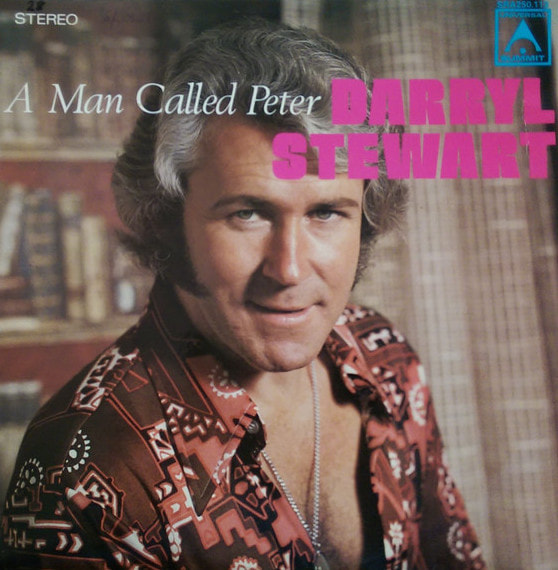

Our first 45rpm vinyl single is usually cited as Festival’s release of Darryl Stewart on “A Man Called Peter,” in 1955. Or was it? Stewart certainly built a career on it. But collector James Cockington recently turned up a 7” by Frank Johnson and his Fabulous Dixielanders, a version of “When the Saints Go Marching In,” whose Magnasound label copy reads that it was recorded on February 21, 1954.

Certainly, Festival’s second 45 and one of its last 78s, in mid-1955, was Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock.” And obviously nothing was the same again after that. |