VINYL AGE, PART TWO: ROCK REVOLUTION

|

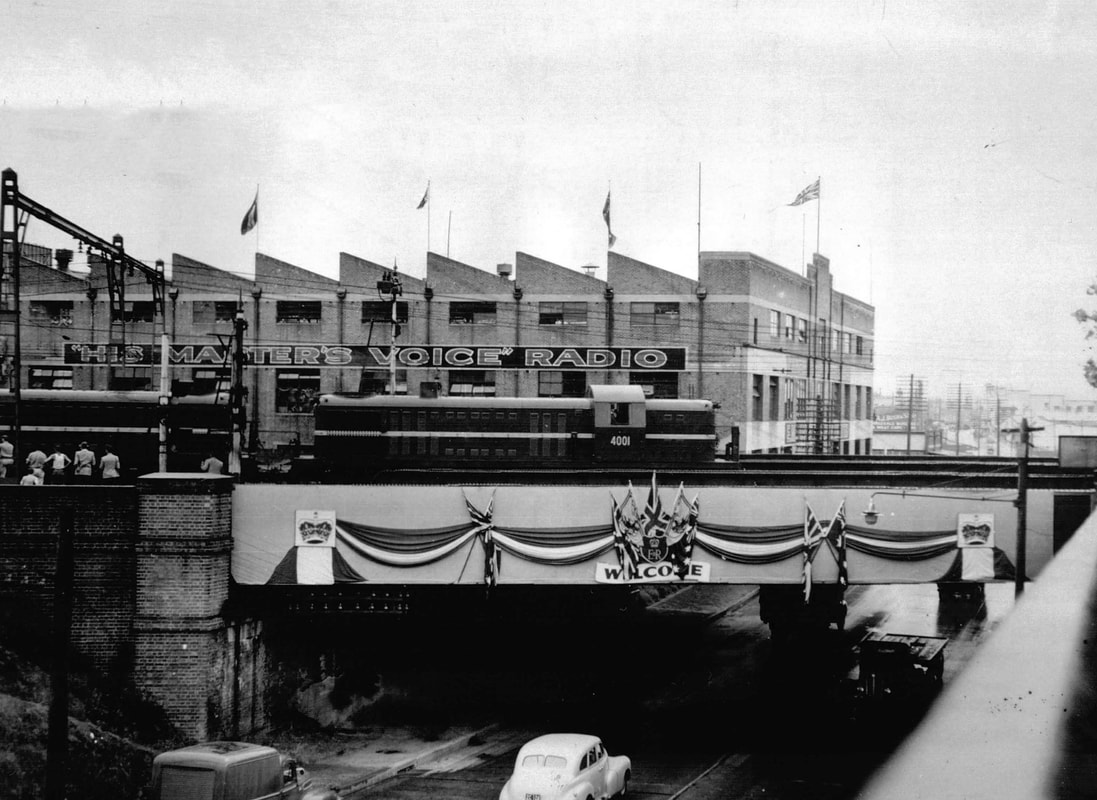

On top of the advent of rock on 45s, the record business in the mid-50s was already lining up for a seachange anyway, with a profound realignment of global alliances. EMI, since its major source of American repertoire CBS had shifted its alliance in Britain and Europe to the aggressive new Philips label from Holland, was looking for a new two-way exchange with America, for a new source of repertoire for its home market, and to get its own foot in the door there. It got all that when in 1955, it completed a buyout of Capitol. One consequence of that was that EMI had to divest itself of the Commonwealth licenses it had long held with RCA. In turn RCA was freed up to pursue its own greater expansion into territories outside the US. Philips too, by the early 60s, would leave its US distribution set-up with CBS and fully buy out Mercury the same way EMI bought up Capitol.

|

|

What this meant for Australia was: EMI and ARC did a swap – where ARC had previously relayed Capitol releases here, now EMI did. Where EMI had previously relayed CBS releases here, now ARC did. ARC formed the unique if short-lived Australian Coronet label. Where EMI had previously relayed RCA releases here, RCA now opened its own office in Sydney, just in time to capitalise on its new sensation, Elvis Presley. Where EMI had previously relayed here releases by both the Deccas, both the US and UK labels of the same name, now it retained only the rights to British Decca.

|

|

American Decca switched its representation in Australia from EMI to Festival after one of the most embarrassing gaffes in all rock history. When EMI in Sydney demurred on its option or first right of refusal to release the American Decca title, “Rock Around the Clock,” by Bill Haley and the Comets, those rights went up for grabs – and Festival’s savvy Les Welch grabbed ’em. And the record that commercially birthed rock’n’roll transformed Festival as well. The single sold a reputed 150,000 copies – an astonishing number for Australia at the time – although that was likely because many people bought it twice, first as a 78 and then as a 45 (just as they would later do going into the 1990s, replacing old albums with new CDs). Thereafter Festival handled Decca material here, which included subsequent hit rock’n’rollers on the Brunswick sub-label like Buddy Holly and Jackie Wilson.

|

|

The rise of rock and the 45 went hand in hand. The album, as it grew from 10” to 12”, was an expensive format for grown-ups who could afford it. The single was cheaper and faster, the jukebox quick shot that suited teens and the times. Festival further went on to virtually scoop the entire pool of first-generation Australian rock’n’roll, signing up the Big 5, Johnny O’Keefe, Col Joye, Johnny Devlin, Digby Richards and Johnny Rebb.

EMI, ARC/Coronet, RCA and Philips trailed miles behind Festival in terms of tapping into local rock’n’roll. RCA was busy enough pressing all the Elvis records it could. EMI was busy with its extensive local hillbilly roster and with its new licenses with Capitol and other new American indies, which brought it hits like Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Gene Vincent and others. Coronet and Philips, like their parent companies overseas, seemed more interested in MOR, although, bizarrely, Philips might have released the very first Australian rock’n’roll side of all when in 1955, in an attempt to beat everyone to the punch, Musical Director Gaby Rogers got Vic Sabrino to cut a knockoff of “Rock Around the Clock.” Sabrino was the nom-de-plume of George Assang, a Torres Strait Islander who sang blues and skiffle, and though his version of the Haley anthem was manful, it didn’t stand a chance against the original when it came out. (Later, in the early 60s, Sabrino would return to Philips to cut an album of gospel songs, the first of its type, with his brother Ken.) (For a full investigation of the question ‘What was the first Australian rock’n’roll record?’ go to the BODGIE BOOGIE re-mix here.) |

|

ARC did a deal with promoter Lee Gordon to back his label Leedon, which both leased American sides from (the Mafia-backed) Roulette Records and also generated its own local titles under the stewardship of the Wild One himself, Johnny O’Keefe.

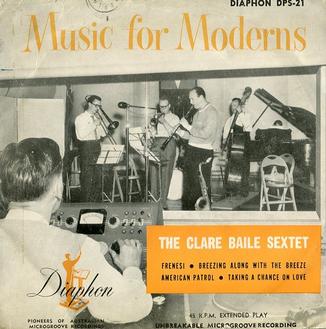

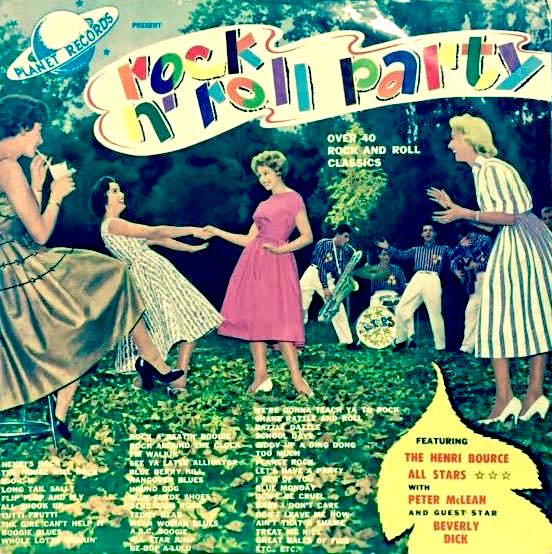

It was in this climate in the second half of the 50s that Australian record sales finally passed the previous, late 20s’ height of 4m per annum. The 45 rpm single grew from next to nothing in 1955 to 2m by ’57, to 4m the following year, 1958; that 4m figure was double the sales of 2m LPs in the same year. Most of the pre-rock indies with the exception of Astor, W&G and Swaggie faded. Planet, after a long string of releases of party records mainly, morphed into Crest. Diaphon disappeared. The first charts came in around this time. The first Australian Number One, in the winter of 1958, was Slim Dusty’s “Pub with No Beer,” which reputedly sold 130,000 copies. It was Slim’s last Regal-Zonophone 78 before EMI graduated him to its more prestigious Columbia imprint and the new two new vinyl formats, 45 and 33. The numbers “The Pub” generated were unheard of, up until that time, for an Australian artist. The record business is one in which most of its products lose money. It’s one big gamble in which every release hopes to be a hit. And 99% aren’t. And then, many hits are but one hit wonders. The holy grail is an overnight sensation with legs, the superstar act: Record companies exist in pursuit of these profit-makers, and the difference in earning power between them and even the top of the second division is so enormous that record companies have sometimes almost been able to retire on one star alone (like RCA did with Elvis!). Sometimes whole catalogues have been bought and sold on the basis of one act. At the same time EMI was hitting with “The Pub,” its Columbia 45 of Jimmy Little’s “Give the Coloured Lad a Chance” was the first Aboriginal protest song on wax. The first black Australians on wax were the singing duo Olive and Eva, whose first release was a Prestophone 78 in ’55, “Old Rugged Hills b/w Rhythm of Corroboree.” Johnny O’Keefe was already a star in 1958, but the first rock’n’roll Number One wasn’t till late ’59, when Col Joye’s “Oh Yeah, Uh-Huh,” his fifth Festival single, hit the spot. The first rock’n’roll album arrived in 1958, whether it was Johnny O’Keefe’s Festival 10”er Johnny’s Golden Album, or Henri Bource’s All-Stars’ 12”er, Rock’n’Roll Party, on Planet Records. |

|

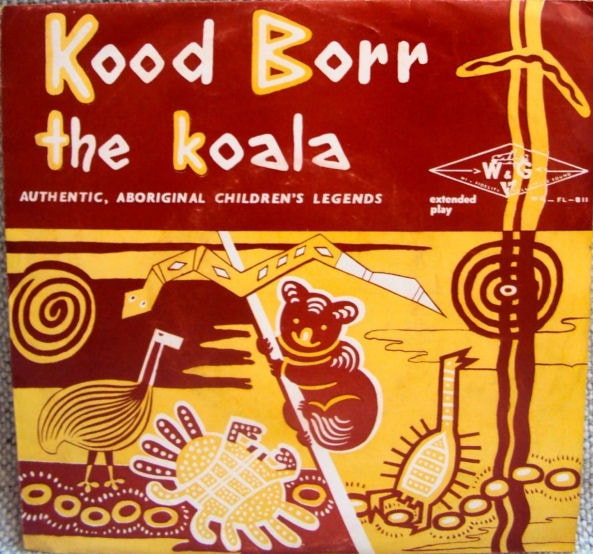

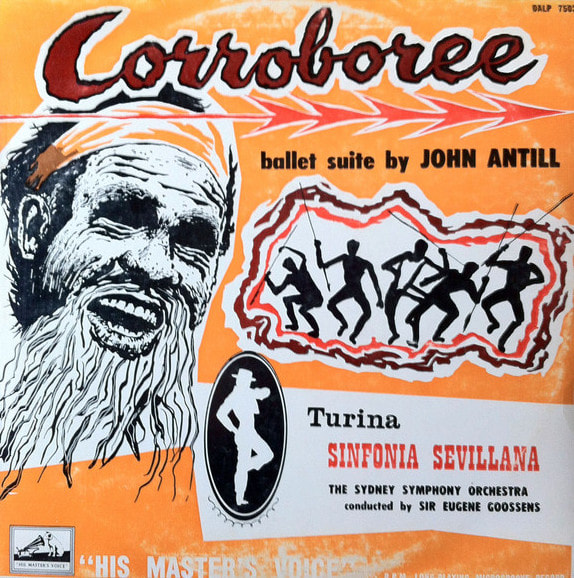

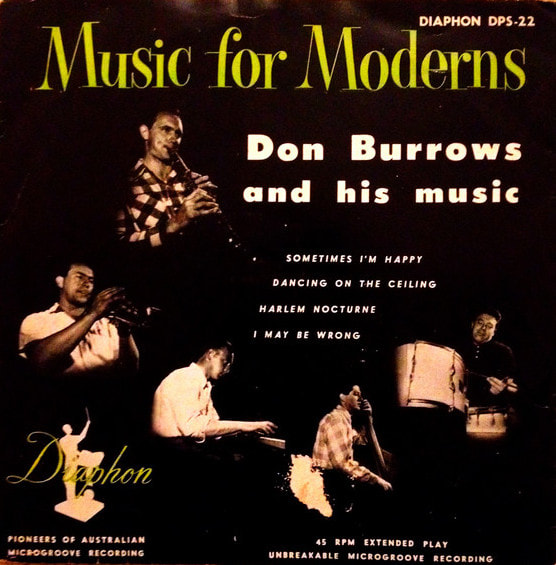

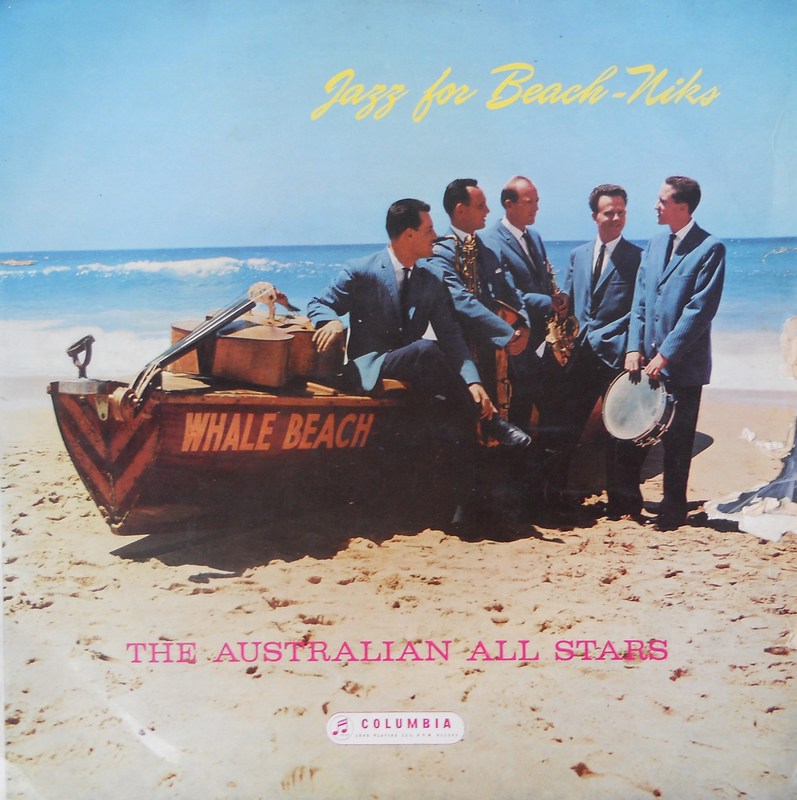

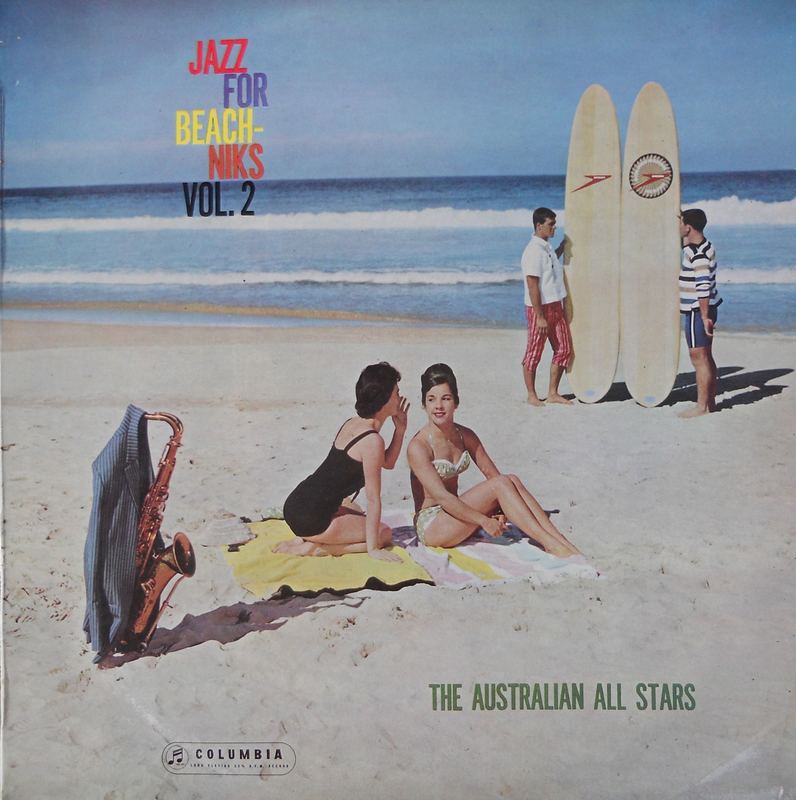

EMI was disinterested in raucous rock’n’roll but was very successful with other, more established genres. In 1958, it released the first Australian stereo album, the cast recording of the Elizabethan Theatre Trust’s production of Lola Montez, the stage musical about Australia’s infamous goldfields hoofer. The label was scoring with other hillbillies too, like Smokey Dawson, Chad Morgan and Frank Ifield (to add to a stable that already included Buddy and Slim), and it would add a folksy flavour with Lionel Long, Johnny Ashcroft and ultimately, most successfully, Rolf Harris. It would release two lavish 12” album volumes of anthropologist A. P. Elkin’s field recordings of traditional tribal Aboriginal songs, an album of modernist-classical composer John Antill’s symphony Corroboree, and two volumes of Don Burrows’ trailblazing Jazz for Beach-Niks albums with his Australian All-Stars band. By now the 12” album format was almost universal.

|

|

The period’s revival of traditional folk music was tapped by independents like Wattle and Score. Score released an EP by Barry Humphries, Wild Life in Suburbia, before the future Edna Everage defected to EMI, and it released an EP by Aboriginal tenor Harold Blair. Wattle went on the preserve an extensive catalogue of irreplaceable Australian folk songs.

|

|

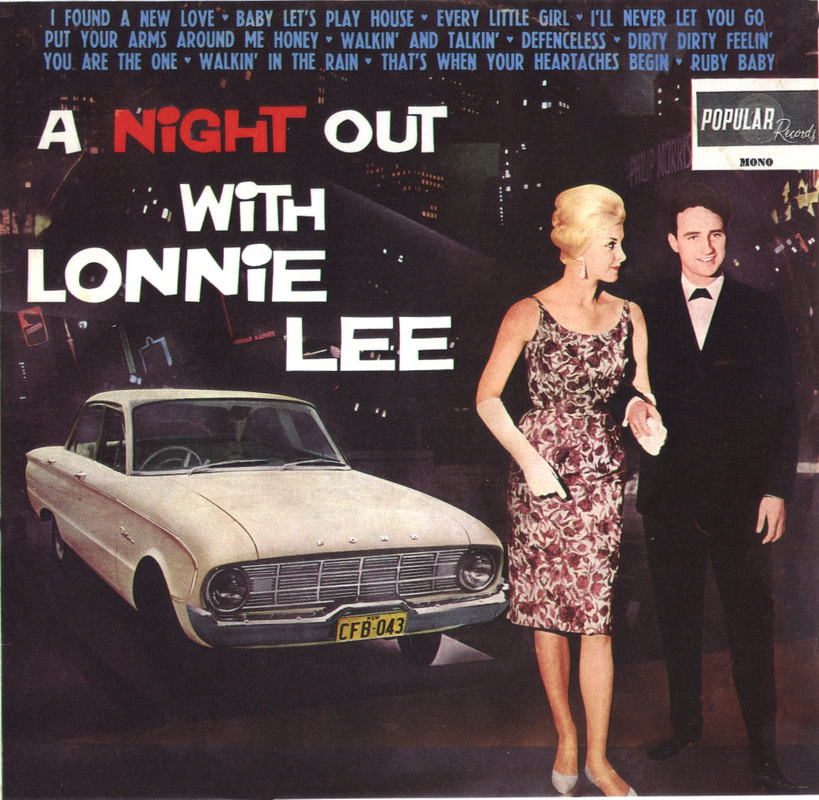

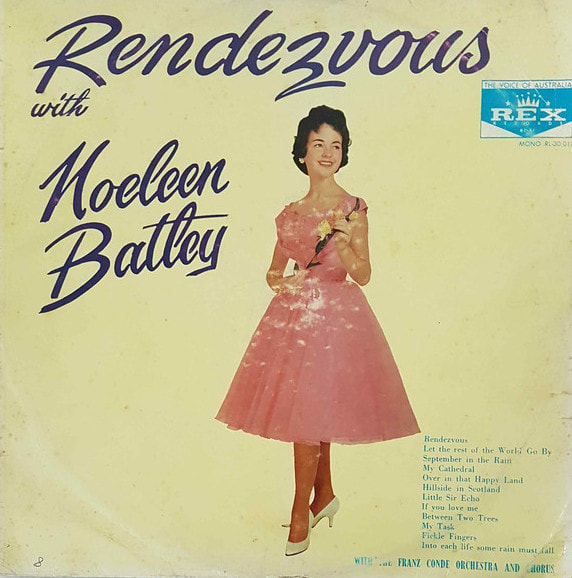

At the dawn of a new decade, the soon to be Swinging 60s, another sea-change: Philips bought up Mercury, Rupert Murdoch bought up Festival, and CBS effected a complete takeover of ARC. Murdoch appointed Fred Marks to run Festival and Marks started aggressively seeking new licensing deals all over the world. One of the first was with Herb Alpert in LA, and off the back of the success of Alpert’s Tijuana Brass, A&M Records would be an enduring money-maker for Festival for the next three decades. It scored early with other lucrative licenses too, with labels like Atlantic, Imperial, Liberty, ABC and Paramount. Festival improved its own recording studio to an Ampex 2-track set-up, and channelled releases through subsidiary labels like Rex, Teen and Leedon, which it bought from Lee Gordon. In time for Christmas 1960 was JOK protege Lonnie Lee’s lavish album A Night Out with Lonnie Lee on Leedon.

|

|

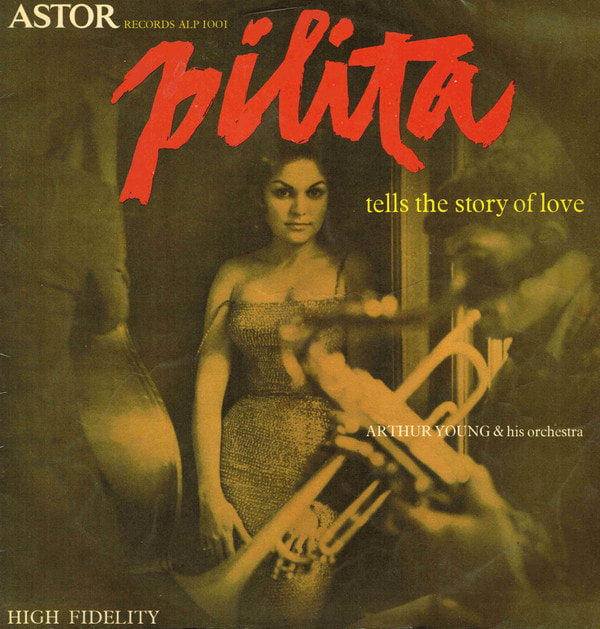

When CBS took over ARC, it started phasing out the Coronet imprint to be replaced by CBS proper, the fabled orange and black eye, and importantly it brought with it the new Warner Brothers Records imprint too, which was just hitting with the Everly Brothers and Peter, Paul & Mary. Coronet generated very little local repertoire, its first release by an Australian artist being a live album by modern jazz pianist Bryce Rhode, in 1960. Around the same time, the label released what is probably the first album by an Australian woman, an eponymously-titled debut by alluring singer Diana Trask, although admittedly this disc was generated and recorded by CBS in New York, where Trask had moved. The first album recorded by a woman in Australia was likely Filipino singer Pilita’s Pilita Tells the Story of Love, also in 1960. It was also Astor’s first local release.

|

|

In 1961, Georgia Lee Sings the Blues Down Under, on Crest, became the first album by an indigenous Australian.

It was as soon as this time, the early 60s, that sales of albums caught up with those of singles, or 45s, at about four million each per annum. Before decimal currency was introduced in 1966, a single cost 10s, an EP 17s, and LPs up to and over three quid. This was quite expensive. For one thing, unlike books, records were subject to sales tax; literature was obviously a much higher form than popular music. But as records’ prices remained fixed for the next twenty years, they became relatively much cheaper, and as cheaper Japanese stereos and radiograms also swamped the market, the real boom was on. |

|

Astor was still hesitant about local repertoire. And though it obviously lost its rights to the Mercury catalogue when Philips bought up the Chicago label, it made up for that by doing new deals with American jazz, folk and blues specialists like Vanguard, Verve and Elektra, and with British Pye – all of which would ultimately deliver hit acts like the Kinks, Donovan, the Doors and many others. W&G, on the other hand in Melbourne, with Ron Tudor at the helm and Bill Armstrong behind the console in his studio, would tap into emerging Melbourne instrumental rock, and the trad jazz and folk revivals; Tudor signed the Seekers to the label.

|

|

|

W&G, on the other hand in Melbourne, with Ron Tudor at the helm and Bill Armstrong behind the console in his studio, would tap into emerging Melbourne instrumental rock, and the trad jazz and folk revivals; Tudor signed the Seekers to the label.

|

|

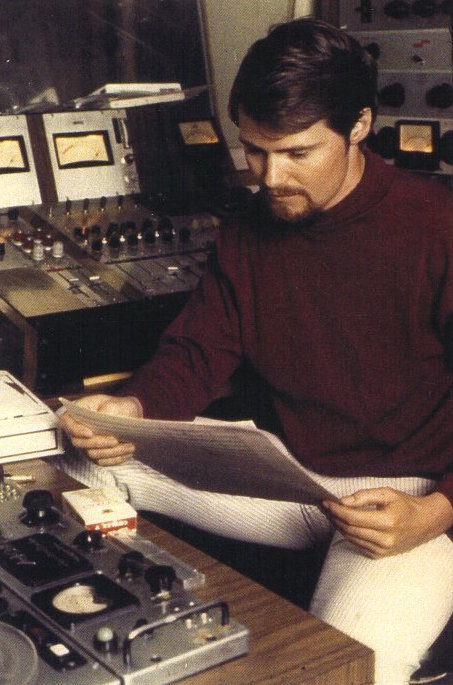

RCA in Sydney was finally moving into local recording, and the new now-renamed CBS operation leapt into the scene too. RCA hired as A&R manager Johnny Devlin even as he was still signed as a performer himself to Festival, and with a brand new studio in the AWA building in Sydney at the cutting edge of four-track technology, the label went aggressively into folk, rock and the new surf sound. Folk music was popular with record companies because it was cheap to record, usually just a solo singer with an acoustic guitar. CBS got in as producer/A&R manager Sven Laibek, who’d arrived in Australia from Sweden almost by accident, and he hit with the cream of the surf sound, the Atlantics, with the timeless 1963 classic, “Bombora;” the Atlantics were also responsible for CBS’s first local rock album. Additionally, just as its US parent boasted the likes of Dave Brubeck and the young Bob Dylan on its roster, CBS here did some sophisticated jazz (as well as Bryce Rohde there was Judy Bailey) and was getting out some folk albums too, launching the careers of Gary Shearston and Doug Ashdown.

|

|

But the Beatles-led British Invasion was about to change everything again.

|