VINYL AGE, PART FOUR: WIDE OPEN(ING)

|

Yet even as the album-rock revolution was threatening, the new King of Pop was Johnny Farnham. Signed by EMI, Farnham led a teenybopper bubblegum juggernaut that took the ascendancy from acid rock because the record companies thought it was a safer, more controllable option – which it probably was. But the underground stirrings in Sydney and Melbourne would soon come to fruition after the bubblegum bubble burst. Bubblegum was a teenybopper singles thing, after all, and ever since – or at least at least up until punk in the late 70s – 45s would suffer disdain as crass and commercial. Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin wouldn’t allow the integrity of their albums to be tampered with by letting the record company pull singles off them. And the record companies were happy enough to play this game because as with so much during this period, it was selling anyway – so why not?!

In the UK a new wave of independents like Island and Chrysalis and boutique labels like Harvest (a subsidiary of EMI) and Vertigo (a subsidiary of Philips, or rather Phonogram as it was now becoming known) were tapping in to this new heavy rock. EMI in Australia used the Harvest imprint extensively for local acts like Spectrum, and Festival launched its own Infinity label and struck license deals with Island and Chrysalis. |

|

Festival also launched its own international outlet, or at least an office in London, which was run by Peter Gormley, the Australian who as Frank Ifield’s manager had taken the yodeller to the UK and onto worldwide success, and then taken over management of Cliff Richard. Gormley generated original releases that Festival International licensed to other labels around the world, and put out in Australia on the Interfusion label; in this capacity, Festival was instrumental in the revival of artists like Tina Turner, Janis Ian and Neil Sedaka, whose “Wheeling, West Virginia” and Working on a Groovy Thing album were recorded at Pyrmont.

|

|

After Warner Brothers in the US bought up Atlantic and then Elektra to form WEA, the new conglomerate split from CBS in Australia in 1970 and took the album initiative and Tamam Shud with it. WEA here released the Shud’s second album Galootionites and the Real People, and the second album by Axiom, headhunted from EMI. WEA also did a label deal with G. Wayne Thomas and his Warm & Genuine Records, which yielded the Morning of the Earth soundtrack album.

Philips did a deal with former W&G/Astor man Ron Tudor, whereby Tudor’s June Productions leased masters to the label, including singles by bands like Bon Scott’s Perth bubblegum outfit the Valentines. But really June was just the pre-dawn of Tudor’s own Fable label, which would launch in 1970 with a P&D (production and distribution, meaning manufacture and distribution) deal with Phonogram, nee Philips. Fable would enjoy enormous success with a roster of almost pure schlock. At the same time, Phonogram, still with some of Philips’ bipolarity, also had a license deal with jazz promoter Horst Leopold and his 44 Records label, whose extensive catalogue remains an extraordinary one. |

|

Leopold also managed Max Merritt and the Meteors and Renee Geyer, who he channelled through RCA recording deals. In 1970, RCA released the eponymously-titled Max Merritt album that was rivalled only as a quality local product that year by Jeff St.John and Copperwine’s Spin album, Joint Effort.

In July 1970, Adelaide independent Sweet Peach Records release Australia’s first double-album, Doug Ashdown’s Age of Mouse. Spectrum’s Harvest double-set Milesago, their second album, did not follow for another eighteen months, till Christmas 1971. In the early 70s, as the US withdrew from Vietnam and the flow of servicemen into Sydney and Brisbane slowed, the emphasis in Australian music shifted back to Melbourne again, for the consummation of our own post-psychedelic album rock. The timing was apposite. Gough Whitlam became Prime Minister and Australia enjoyed a new dawn of confidence and optimism. There were three distinct generic strains emerging in Melbourne: the hard-rockin’ blues’n’boogie of bands like the reborn Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs, Chain, Carson and the Coloured Balls, which was related to early heavy metal but also laid a blueprint for local pub rock to follow; the more cerebral head bands, or progressive/hippy/trippy outfits like Spectrum, Company Caine, MacKenzie Theory, Ross Wilson’s Zappa tribute band Sons of the Vegetal Mother and even jugband Captain Matchbox; and in the wake of the demise of Axiom, a country-rock push that first produced the solo Brian Cadd, followed by the Dingoes and eventually Little River Band too, not to mention former Go-Set writer Greg Quill’s seminal Sydney outfit Country Radio. |

|

The band that defied these categories was Daddy Cool, who started out as a sort of side-project to the Vegetal Mother and ended up transcending all, in 1971 redefining the reach of Australian rock. Whether or not the majors were interested in DC, the band signed to new local indy Sparmac. Sparmac was an offshoot of the Tempo distribution house which had been formed in Melbourne in the 60s to pick up some of the slack left by the majors (like locally releasing lots of Atlantic Records’ catalogue of deep soul); Tempo would go on to also launch its own in-house Image Records label, which signed Captain Matchbox among others, and it handled distribution for local jazz and blues labels like Cherry Pie, Cumquat and Eureka. Sparmac released the debut Daddy Cool single “Eagle Rock” in June 1971 and it sold out two pressings in a week in Melbourne (a pressing was probably around 3-5000), going straight to Number One nationally and staying there for eight weeks. The album that followed, Daddy Who? Daddy Cool!, would sell a phenomenal sixty thousand copies. No Australian album had ever come close to these sort of numbers, and it proved that, a) local rock could match the popularity of the biggest imports, b) local albums could do the same, and c) it could be done independently.

|

|

A similar manufacturing-distribution set-up to Tempo’s was launched out of Sydney in the early 70s, called M7, because it was initially linked to TV’s 7 network. Launched by Allan Crawford, the Australian record man who’d launched American publishing company Southern Music in Australia, discovered Frank Ifield and played a major role in the inception of British pirate radio, M7 went hand in hand with the formation of Larrikin Records, Warren Fahey’s folk label. The M7 label itself would go on to enjoy such significant hits as Bob Hudson’s 1975 comic folk classic “The Newcastle Song,” which was an indication of the way indies have always been less hidebound than majors, less afraid of the non-formulaic.

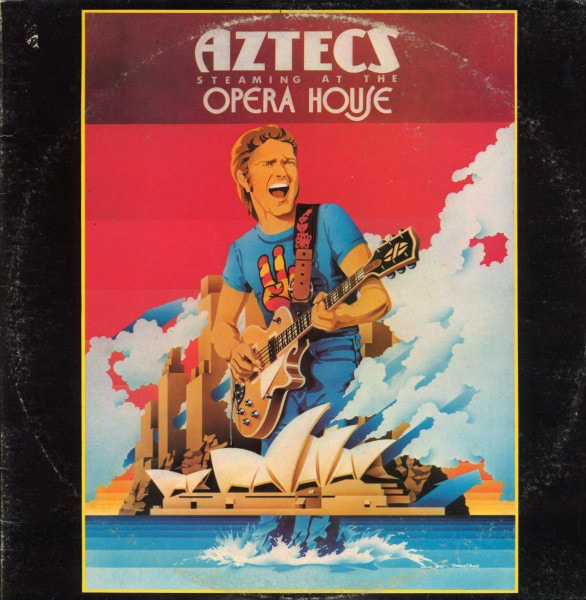

With the inception of outdoor festivals at this time too, the whole configuration of live music was expanding. No longer was a couple of old speakers in a church hall sufficient. In 1972, the resurgent Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs redefined the parameters again. Armed with their new Strauss amplifiers and massive PA stacks, the band cut a comeback album, The Hoax is Over, for Infinity in ’71, but still they felt constrained, and so formed their own label Havoc Records, with a distribution deal with Astor. And during ’72, with Aztecs Live and the Live at Sunbury double set, the band repeated Daddy Cool’s ’71 sales figures but twice over! Havoc manufactured its records in New Zealand in order to not only get superior pressings (Australian pressings have notoriously always been poor) but also more lavish packaging. But the label quickly folded when one of its backers died, and Thorpie himself fled to Sydney to sign to WEA. Astor ever after tended to concentrate on lucrative international licensing deals (after losing Elektra, obviously, to WEA, it took MCA [nee Decca] away from Festival and picked up Casablanca Records, which would deliver it Kiss and Donna Summer), but with its Australian parent company being bought out in the early 70s by Philips, its future was inevitable as part of Phonogram morphed from Philips into, eventually, PolyGram. |

|

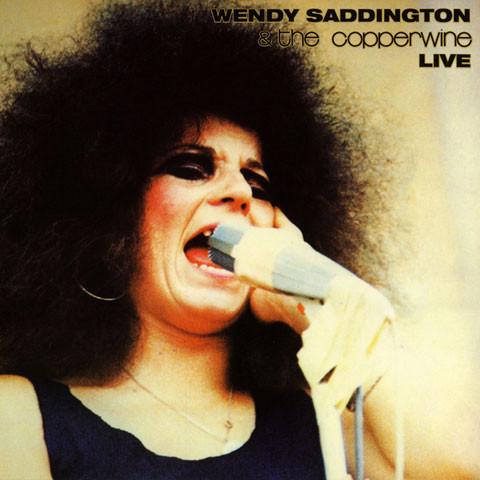

The Aztecs weren’t the only band disgruntled with Infinity. In 1970, Chain had cut a debut album for Infinity called Live Chain (another of those cheapskate Festival live albums; the same treatment was meted out to Wendy Saddington and Country Radio, thus frittering much potential). But Chain’s manager, dance promoter Michael Gudinski, wanted better treatment for his band, and it was this feeling that inspired him to form one of the defining Australian record companies, Mushroom. The majors, it has to be said, were probably working at full capacity. EMI signed Carson as well as Spectrum to Harvest and released the Rock’n’Roll Sandwich album by a rejuvenated, power-trio version of the La De Das. Infinity put out the classic Blackfeather (studio) album At the Mountains of Madness. Phonogram signed Brisbane band Buffalo to Vertigo, and WEA signed La De Das’ spinoff the Band of Light, among others like Kush and Kiwi power trio Ticket. But that didn’t mean there wasn’t still a glut of talent on the Melbourne underground that Mushroom could tap into.

With a P&D deal with Festival, Mushroom was launched in March 1973 with the lavish triple album set, Australia’s first triple and a sort of answer to Woodstock, The Great Australian Rock Festival: Sunbury 1973. But neither that nor the label’s other early releases by the likes of Madder Lake and MacKenzie Theory sold, and Mushroom initially struggled. |

|

Much more immediately successful in Melbourne was Bootleg Records, the label Ron Tudor’s Fable formed to launch the solo career of Brian Cadd. Just as he had in his previous band Axiom with hits like “Arkansas Grass,” Cadd was tailoring his (‘West Coast’) sound for the American market, and though he would eventually move there he would never enjoy the success fellow ex-Axiom singer Glenn Shorrock would with LRB, he was ubiquitous in 1973 with two huge hit albums, Parabrahm and Moonshine.

Concurrent with the Melbourne rock renaissance was another folk revival. EMI signed the likes of Jeannie Lewis and Ross Ryan, and out of this push would ultimately emerge, on indy labels like Sweet Peach, Billingsgate and Larrikin, some of the staples of the Australian songbook, like Kevin Johnson’s “Rock’Roll I Gave You All the Best Years of My Life,” Doug Ashdown’s “Winter in America” and Eric Bogle’s “And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda.” RCA, again replicating its US parent, which was scoring big with the outlaw country of the likes of Waylon Jennings, revived the careers of the likes of former first-generation rock’n’roller Digby Richards, who made a string of superb albums in the mid-70s. RCA also released the country-rock album recorded live in Bathurst jail by Aboriginal inmate Vic Simms, The Loner, and the Ted Egan–penned land rights single by Galurwey Yunapingu “Gurindji Blues;” it would later move into the truckin’ songs of Nev Nicholls and John Laws, which sold truckloads. Jazz enjoyed a sort last gasp in the sun through its fusion with rock in the form of bands like Galapagos Duck (44 Records) and Crossfire (EMI). Mushroom continued to struggle till it signed Skyhooks. And in that was the beginning of a whole other new era, what might be called the Countdown Era of the mid-70s, Countdown the weekly ABC TV pop show the premiered in 1974. |

|

If the early 70s in Australia was the late 60s we missed out on, the mid-70s, with the introduction of colour TV, was our glam rock era. The yin and yang or Stones v. Beatles of it all was Skyhooks and Sherbet. Festival in effect owned them both. Countdown became a family just as surely as Bandstand had been one; it was (host) Molly Meldrum, and Skyhooks and Sherbet, JPY, Marcia and Hush, TMG and AC/DC. Even though the national mood was supposed to be downcast after Whitlam’s dismissal, Countdown was release and celebration every Sunday on your TV set. Every day on the radio and your record player or, increasingly, cassette player, Australian rock was cutting through.

|

|

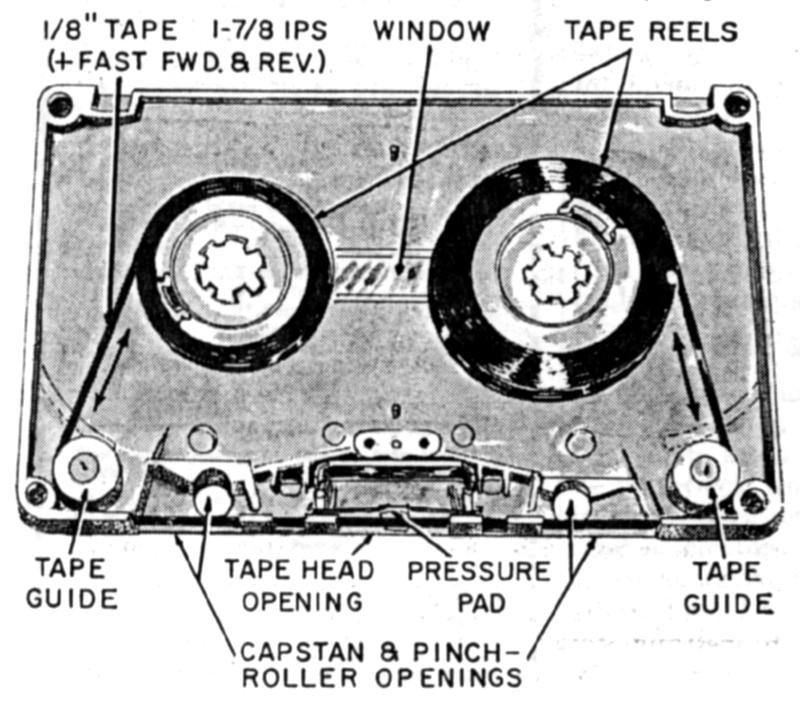

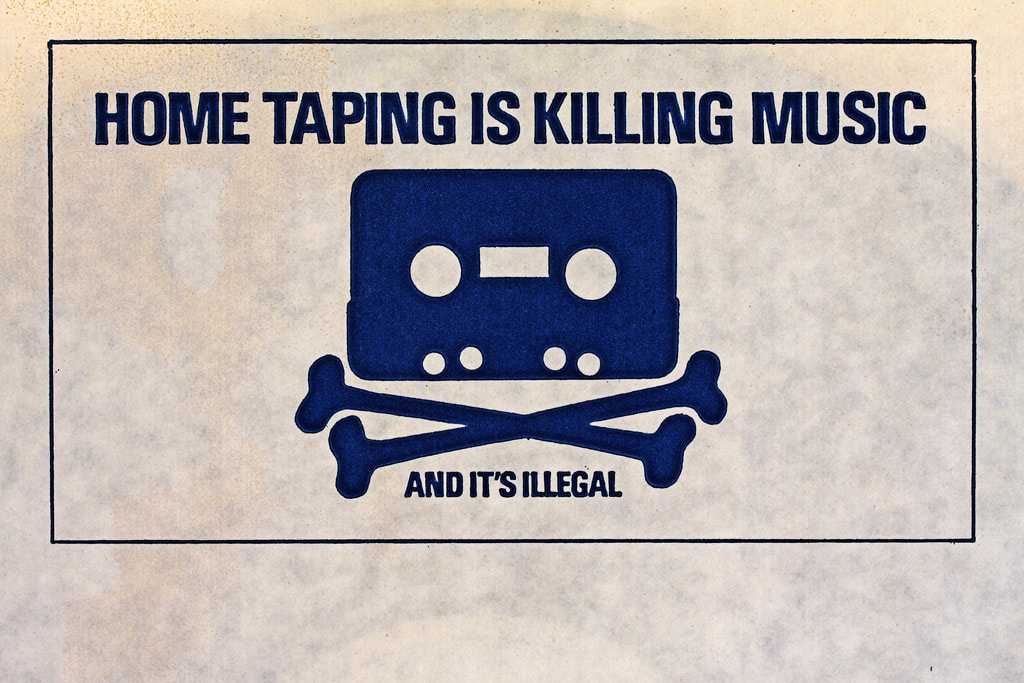

In 1973, CBS opened its first cassette plant at Artarmon in Sydney. Developed by Philips, the cassette’s great asset was its portability, and as in-car players spread rapidly (superseding the short-lived Betamax of the format, the 8-Track cartridge), sales of tapes, both blank and pre-recorded, took off. The record companies’ kneejerk response was to launch the ‘Home taping is killing music’ campaign, but as record sales continued to grow, it seems that home taping wasn’t killing music but further encouraging its reach.

|

|

The Skyhooks blew away the records Daddy Cool and the Aztecs had set only a couple of years earlier. Both their first two albums Living in the 70s and Ego is not a Dirty Word sold over two hundred thousand copies each, and this entrenched Mushroom.

The majors were only tending to get a bit of this action via label deals like Festival had with Mushroom. Sherbet were with Infinity. So much of the rest of the action was carved up by just two labels, both from Sydney, Alberts and Wizard. Alberts were still in bed with EMI and Wizard was with Phonogram. Alberts had JPY, TMG, AC/DC. Wizard had Marcia and Hush. Alberts had launched as a label in its own right in 1971 with Ted Mulry’s syrupy ballad “Falling in Love Again.” When ex-Easybeats songwriters/producers Harry Vanda and George Young soon came back to Australia complete with a mixing desk from Abbey Rd, Alberts became a hit factory whose legacy is some of our most iconic songs, from the rare Australian disco of JPY’s “Love is in the Air” to the classic rock’n’roll of AC/DC’s “Long Way to the Top.” Disco was about to take over the world, no small thanks due to expatriate New Australian band the Bee Gees, but Australia itself produced almost no disco music of our own, apart from the above and a few other isolated items by soul divas like Marcia Hines and Renee Geyer who would furiously deny they were disco anyway. Disco’s still-birth as a living generic entity in Australia may have something to do with racism, homophobia and misogyny. It was music, after all, for sheilas, wogs and poofters. Wizard Records had grown out of Sparmac. Sparmac had been bought up by Robie Porter, former early 60s popster Rob E.G., who’d spent the late 60s in LA. In the 70s, Porter went bi-coastal, or mid-Pacific, pushing in the US Daddy Cool (unsuccessfully) and Rick Springfield (very successfully). He could see how even only moderate US success like Springfield’s (off the back of the single “Speak to the Sky”) could yield massive sales of three hundred thousand albums. In Sydney he morphed Sparmac into Wizard with a P&D deal with Phonogram and scored with Hush and Marcia Hines. He would go on to engineer Air Supply’s breakthrough in the US. EMI had acts of their own too, like LRB and Mondo Rock, but CBS and even WEA lapsed and had some catching up to do. Next to its country roster, RCA was probably too busy pressing ABBA records to do much else. CBS, now under new American boss Paul Russell, re-entered the fray, signing Rabbit in 1975, and hitting as soon as the following year when house producer Peter Dawkins signed Dragon and Air Supply. WEA stepped up in 1977 when new A&R manager Phil Mortlock, under new MD Paul Turner, signed Cold Chisel: This was the pendulum swinging back to Sydney in readiness for the corporate 80s to come. Countdown was losing primacy by the later 70s. Countdown could make or break a record, but it was now the pub circuit that was producing the bands. Emerging FM radio wasn’t interested in teeny pop either but rather the classic rock sound that Chisel and other bands like them would come to personify. This was the beginning of the golden age of pub rock. In February 1978, Mushroom released Australia’s first 12” single, Skyhooks’ “Women in Uniform.” The 12” would become a staple of emerging dance music particularly, and perhaps the optimum fidelity ever made. Mushroom’s revival of the 10” (mini-)album, however, with the Models’ Cut Lunch and The Sports Play Dylan (and Donavan), was just a gimmick and less enduring. But fun for collectors. Recording technology was now becoming very sophisticated. In 1977, jazz organist Steve Murphy and his Quartet had cut Australia’s first direct-to-disc album under the supervision of Astor Records’ technical manager Harry Mauger. In 1979, jazz singer Kerrie Biddell cut what was proclaimed as Australia’s first digital recording at EMI’s Studio 301 in Sydney, the album Compared to What. But both these recordings were in a way a throwback to the old days of one-take performance. Multi-track mixing, 16 and 24-track, was now the norm. Alberts had set a benchmark with its legendary studios in Boomerang House in Sydney, and now everyone wanted to use more tracks, spend more time. Meaning more money. Certainly commercially, pub rock took ascendancy over punk, which was starting to bubble up of its own volition in Australia as around the world, because pub rock was like the full flowering of an already established tradition rather than punk’s radical and anti-social departure, and could thus be readily understood by a wide audience (not to mention the record companies). Pub rock was the consummation of a tradition arguably begun in Melbourne in the early 70s by blues’n’boogie bands like Chain and the Anzacs, and diversifying in the mid-70s through AC/DC, the Dingoes and Richard Clapton: You can hear all these things in Chisel, the Angels, the Oils, Australian Crawl. It was a feeding frenzy for record companies big and small. Mushroom signed the more roots-influenced Sports and Jo-Jo Zep and the Falcons, and Paul Kelly, and almost virtually re-launched Split Enz. The other man in Melbourne, Glenn Wheatley, had Australian Crawl join his own Little River Band at EMI. Alberts signed the Angels and Rose Tattoo. CBS signed Mi-Sex. Martin Fabinyi’s new Sydney label Regular, in a link-up with Festival, signed Mental As Anything and Icehouse. Phonogram signed the Reels to its reactivated Mercury label. Midnight Oil went it independently on their own Powderworks label through M7. New indy DeLuxe, run by ex AC/DC manager Michael Browning through RCA, signed INXS, the Dugites and the Numbers. CBS then headhunted the Angels and the Oils, and WEA would headhunt INXS. |

|

As soon as their second album, 1979’s Breakfast at Sweethearts, Cold Chisel were selling in the six figures. The late 70s/early 80s would transpire to be even bigger than the Countdown era before it. In June 1980, the Top 15 albums in Australia included six local titles: East, True Colours, Dark Room, Boys Light Up, Space Race and an Angels greatest hits collection. Chisel’s East would go on to sell more than any previous Australian album, surpassing 200,000 as soon as 1981. By now, it has sold as many as 350,000.

The majors were all looking for boutique shopfronts to accommodate the renaissance going on in the pubs. EMI already had Oz Records, run by former Daddy Cool frontman/Skyhooks’ producer Ross Wilson and LRB-manager Glenn Wheatley, and it signed Melbourne band Stiletto. CBS pulled in Peter Dawkins’ Giant Records, Astor Rough Diamond, and RCA, Browning’s DeLuxe. The labels might not have lasted but Rough Diamond debuted trailblazing Adelaide Aboriginal reggae band No Fixed Address, and DeLuxe first developed INXS. The sheer magnitude of this greatest renaissance prompted a change in chart rigging. A Gold Record, which had previously been awarded for sales of 15,000, was now upped to sales of 35,000. Platinum was 70,000. At a peak of production, Festival, say, had 26 presses in its plant pushing out 25,000 records per day! On their own label Powderworks through 7 Records, Midnight Oil were able to go gold for sales of 35,000 on their second album, 1979’s Head Injuries. The difference a major makes? The Oils’ fourth album, their second album for CBS, 1982’s 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, went Top 3 and sold a quarter-million - triple-Platinum! More and more acts were selling more and more records. After the Oils left, 7 Records kept the name Powderworks and rechristened itself. Astor along with its winning local MCA and Casablanca licenses would be completely swallowed up by PolyGram, if not before two of the biggest Australian singles of all time, Mike Brady’s “Up There, Cazaly” in ’79 (which has sold 262,000 copies) and Joe Dolce’s “Shuddap Your Face” in 1980 (which sold 320,000). PolyGram’s biggest local act at that time was still Kamahl. But Australia was not immune to the Crash of ’79 that hit the music industry in the US and UK. Overseas, in 1979, the record business business suddenly contracted drastically. It was the first real contraction after 30 years of constant growth, and it was a catastrophe. If 1978 was the peak of the vinyl age, it was followed by the immediate fall in ’79. Australia followed suit, and in the early 80s, sales plummeted by a similar average 20% margin everywhere. After Australians bought 18.5m records in 1982, we bought only 17.6m in ’83, and 16.3m in ’84. The heights of 1978 would not be returned to till the end of the decade, and largely as a result of the CD revolution. |

|

Which of course only made competition even more fierce between the Big 6 majors – EMI, Festival, CBS, RCA, WEA and PolyGram – because even despite the economic bust, there was still a boom going on in the pubs, in the art form. Festival and EMI wrestled at the top of the tree after fully a quarter of the market each, with Festival counting strongly on the success of Mushroom and Regular. CBS and WEA wrestled on the next rung, both striving for a 20% share, followed by PolyGram on around 10% and latterly the likes of RCA and Astor spiralling out of contention. In 1983 the Big 6 got into formation as ARIA. Rock had always been pretty big business, but now it was going corporate.

|