VINYL AGE, PART 6: ENDGAME

|

The early 90s’ PSA inquiry into inflated CD prices and parallel importing had the record business hysterically predicting its own demise. It was only half right - its demise was imminent, to be sure, but the enemy wasn't the PSA but rather encroaching digitisation and the internet. Yet even though the PSA’s recommendations counter to the industry case were emasculated due to taking so long to be implemented, the industry’s hand had been forced anyway and discounting and importing started to really proliferate, meaning sales generally stayed up.

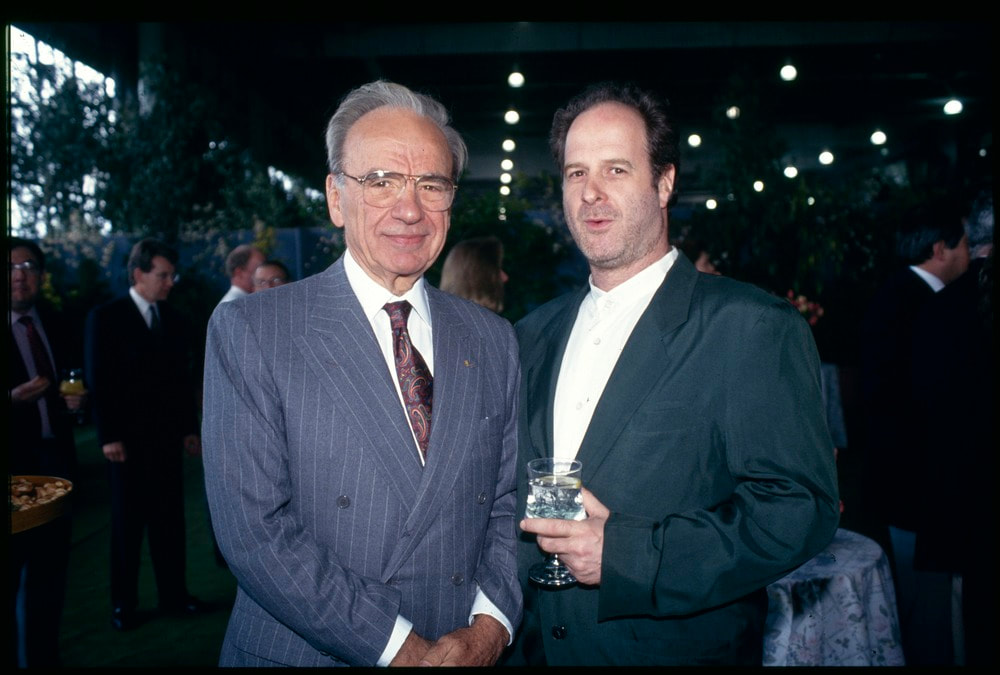

In 1993, Michael Gudinski sold 49% of Mushroom to Rupert Murdoch’s Festival for around $20m. Festival, having lost so much of its licensing income stream, was desperate for catalogue equity – and Gudinski wanted money to open a Mushroom venture in the UK. Rupert Murdoch’s 23-year old son James was installed as Festival-Mushroom Group manager, and FMG, still in need of catalogue, in 1995 bought Warren Fahey’s Larrikin. For Michael Gudinski and Mushroom, their failure to make a mark internationally had long gnawed at them, and would indeed prove to be an Achilles heel. Early on, Gudinski had developed a relationship with A&M Records in LA, and numerous Mushroom acts like Ayers Rock, the Dingoes and others enjoyed US release on A&M. But none of them stuck. Nor did it work when in the early 80s, Gudinski launched his own American boutique label Oz Records through A&M. By the early 90s, Mushroom’s star was on the wane, with only a couple of superstars, Jimmy Barnes and Kylie Minogue, selling any appreciable amounts of records, and Barnsey a frustratingly purely domestic – and expensive – proposition. So with long-time partner Gary Ashley moving to the UK to start up Mushroom International, the label got out of the blocks with the success of the trans-Atlantic band Garbage, and erstwhile Australian pop singer Peter Andre, who’d started out on Molly Meldrum’s Mushroom offshoot label Melodian. |

|

In 1995, after MCA had bought up PolyGram, the new conglomerate morphed into Universal, and it was immediately probably the most powerful force in an industry admittedly already under siege in the face of the infant internet.

‘Corner store’ indies like Half-a-Cow, Fellaheen, Rubber and others now at least had the stable distributor the 80s had always hankered for, Shock, and Shock would outdo even the majors’ attempts (most prominently PolyGram’s iD) to streamline and/or muscle in on independent distribution. Other indy distributors subsequently sprang up, like MGM and Inertia. |

|

Sony created the boutique label Murmur specifically to house teen grunge trio silverchair. This was a measure of the corporate backlash, that it was necessary to project an image that was supposedly independent. Perhaps the most far-reaching Australian music entrepreneur of the period was former Angels’ manager John Woodruff. Heading up an Australian office of new American (BMG-backed) label Imago, Woodruff first engineered the international success of rock-pop outfit Baby Animals. Then he engineered the even greater international success of Brisbane synth-pop band Savage Garden. Both sold vast quantities of records in Australia and around the world.

silverchair sold loads of records too, or rather now only CDs. The digital revolution was pretty complete. If only in the temporal dimension. silverchair’s 1994 debut single sold 180,000 copies, and ’95 debut album Frogstomp over 200,000. But it was a measure of the contraction of rock that even as You Am I, probably the most broadly-respected or influential Australian band of the 90s, could have two successive albums, 1995’s Hi Fi Way and 1996’s Hourly, Daily, debut at Number One, neither shifted more than Gold, or 35,000 copies. Aggregate CD sales were still strongish, but spread thinner over so many more releases, so many more acts, so many more global-tribalised genres… In 1997, Michael Gudinski, fed up with the flailing Festival, which owned 49% of Mushroom, and devastated by the split with Gary Ashley that caused the demise of Mushroom International, took the label’s distribution away from Festival for the first time ever, and over to Sony. The impact on Festival was so great it had to retrench half its staff. Festival was still so desperately trying to stay afloat that it finally bought out the remaining 51% of Mushroom. The ticket price of $43m seems exorbitant considering that by then most of Mushroom’s top talent had deserted it, and its back catalogue was never that deep, but Festival was desperate. Kylie Minogue ran her franchise out of London. Gudinski kept the lucrative publishing arm of the company, and still has a plaything in Liberation Records. |

|

The real last pre-internet Australian record company success story is Modular’s. Modular was launched in 1998 as joint venture between EMI and Steve Pavlovic, a former youth worker who got into promoting gigs in the late 80s and built a mini-empire based on his indy label Fellaheen and its acts like Ben Lee, and his own personal associations with hip American acts like Sonic Youth and the Beastie Boys. Modular became one of the coolest record labels in the world when ‘cool’ was still music industry currency, but there was surely something ominous in the fact that the term ‘retro’ attached itself to so much of what the label did, from the retro rock of its hit act Wolfmother to the retro electro of its hit act the Presets.

What did continue to grow in the 90s, with the spread of home digital recording equipment, was the sheer number of music-makers in Australia and the number of cottage indies, who persisted and still do despite the internet’s penetration. The way Australian music is measured has to change. The biggest Australian acts have to now be considered the likes of AC/DC and Kylie. Barnesy and Farnsey have been notoriously unable to get arrested outside Australia, yet Nick Cave is welcomed like a god everywhere he goes, from Eastern Europe to Latin America. Australia now is merely part of the global tribalism of musical taste. It was still possible to have a blockbuster as late as 2003, by which time aggregate sales were starting what would be the long slide. Delta Goodrem’s second album Innocent Eyes (Sony) trails only Whispering Jack as the second-biggest Australian album of all time, selling through the Sony machine over a million in Australia alone and 4.5m worldwide. The retro ‘new rock’ of Jet and the Vines flashed in the pan, sold a few million, and went back to the small pubs and bars whence it came. Not even Deltra Goodrem was enough to save Sony, and in 2004, it merged with BMG. In 2005, FMG ceased trading as insolvent and its carcass was acquired by Warners. Thus the two great Australian record companies were dead in one. The Australian majors then still numbered 6 but were Alberts and Shock, EMI, Warner-Festival, Sony-BMG, and Universal, and no longer such a Big 6 as a shrinking 6. AIR, the Australian Independent Record Labels Association, which began in 2000 as a loose aggregation of 25 members, was by then a company with 350 financial members. But they were all running scared and all seeking new means of income. CD sales halved in the first decade of the new century. The plastic object was dying. The music industry might prefer to point to growth areas. In 2003, there were only about 30 legal download services on the net, but by 2007, there were more than 500. The digital share of the global music market moved from almost zero in 2003 to 15% by 2007. Unfortunately for the record companies, growth in illegal downloading was even greater, and illegal downloads were estimated to outnumber legal ones by twenty to one. More strict policing of downloading might have come in, but the thing that finally won out was the eventual establishment of legitimate streaming services like Spotify. In 2007, Justin Timberlake's Future Sex/Love Sounds, say, was released in more than one hundred formats (including ringtones, mobile full-track downloads, video, iTunes and others) and it sold a total of 19m units. Only 20 per cent of its sales were CDs. The irony is a rapid regrowth in vinyl sales. The retro album and single are back. For a certain niche market. For maybe fifteen or just five minutes. Or maybe longer. Like twenty minutes per side. In 2007, according to Nielsen SoundScan, Australian vinyl sales approached a million, and by 2008, they were double that, approaching two million. Aggregate disc sales generally, however (excluding the music DVD format), have fallen from an all-time high of around 63m in 2001, to under 30m by 2009. By 2015, the (paying) market for music had almost halved again, with CDs accounting for less than 20% of it. Since the new growth area has become, ironically, live performance – perhaps not so surprising given our increasingly virtual world – record companies are now trying to buy into a piece of that action. But artists, now tasting life free of the servitude to record companies on which rock grew, are unlikely to want to go backwards. Never again will an artist outright sell copyright to anyone. Record companies were only ever possible because they bought, owned and controlled copyrights. To the extent that copyright is any longer controllable at all, the distribution networks are now so much more complex anyway. Artists now want to do what are called ‘360-degree’ deals, where, with the artist at the centre of a wheel, rather than a record company as it used to be, the record company is just one spoke that spins off the hub along with tour promotion, merchandising and other income streams. One English act, Kaitty, Daisey & Lewis, a rockabilly band, has even put out 78s. And if that’s a bridge too far, what is it to be putting out cassettes? as some acts are doing nowadays too! But everybody knows – even if they don’t know it, they can feel it – nothing has ever sounded better than a juicy prime-cut slab of 12” vinyl. Unfortunately for Australian music, that would have to mean an American or Japanese pressing. |