4: BREAKING (UNDER) GROUND

|

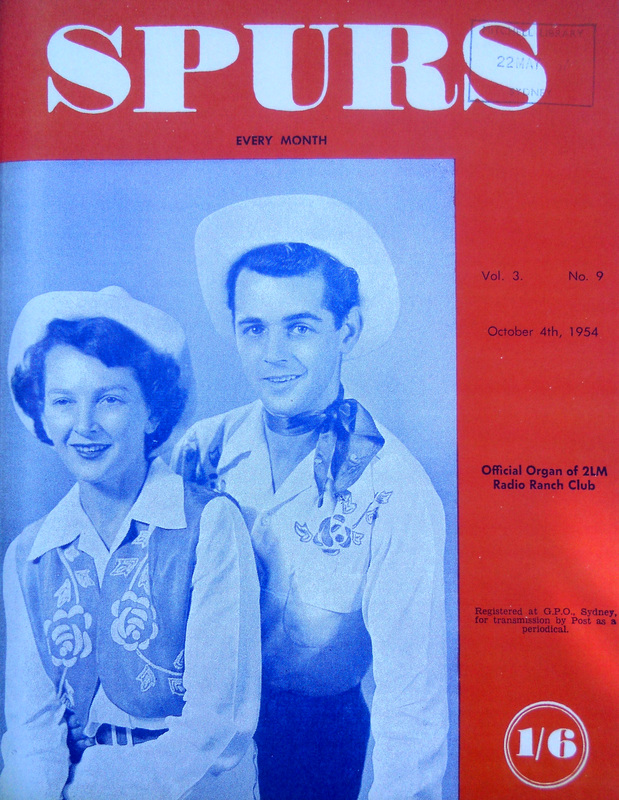

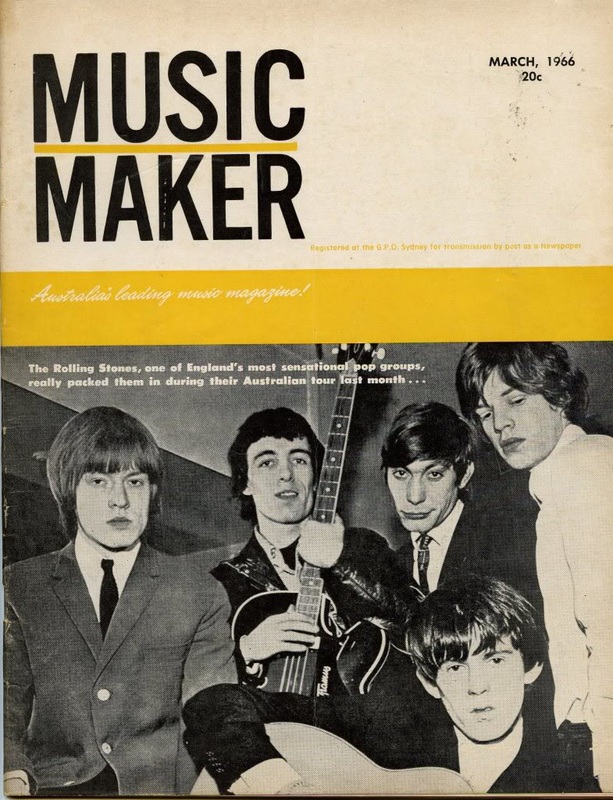

Rock’n’roll first hit Australia in 1955, when Bill Haley sang “Rock Around the Clock” as the title song in the movie Blackboard Jungle. The specialist music press was by then already well-established, with Music Maker serving jazz and Spurs, the hillbilly scene, and both of these were not entirely unhip to this emerging new genre. But as Peter Doyle demonstrates in his article “Flying Saucer Rock’n’Roll,” the conservative mainstream media damned it in the same nigger-jungle/juvenile-delinquent/passing-fad terms as it did in the US. Leonie Kramer was just one of those critics, when the papers weren’t calling in foreign experts like Malcolm Muggeridge to try and explain social deviants like bodgies and widgies.

But as rock’n’roll proved it wasn’t going to go away and, if nothing else, could be extremely lucrative, the popular press had to fall in line. Donald Horne, editor of Weekend magazine, a racier version of the folksy Pix or People that came out of the Packers’ Australian Consolidated Press stable, in 1957 hired a cub reporter by the name of Lillian Roxon - and she would go on, of course, to become the godmother of rock journalism world-wide. |

|

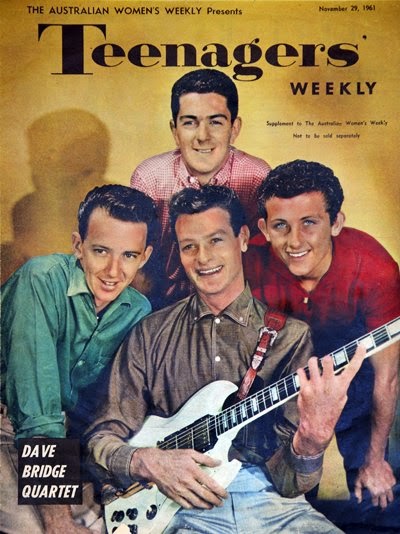

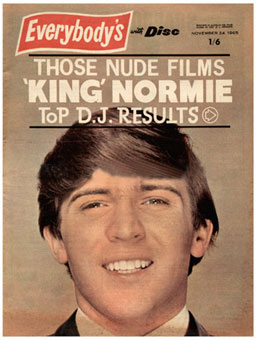

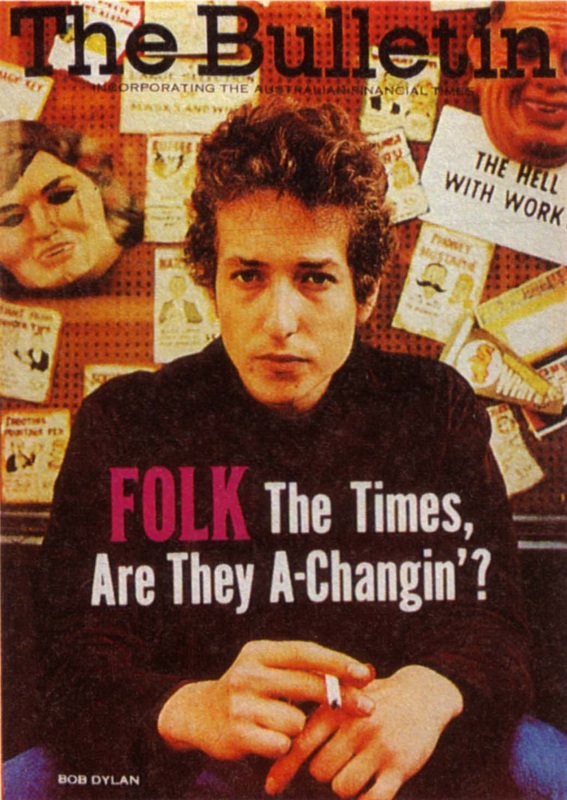

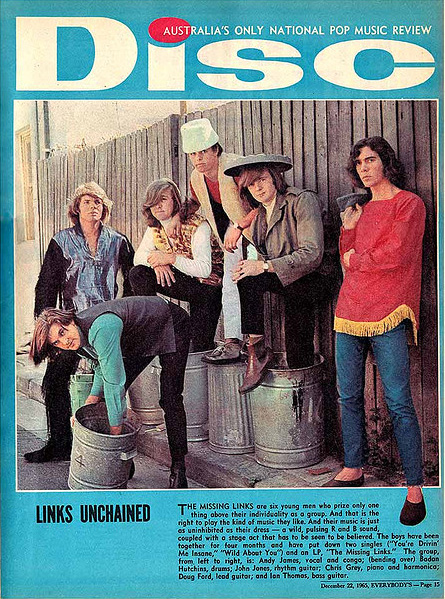

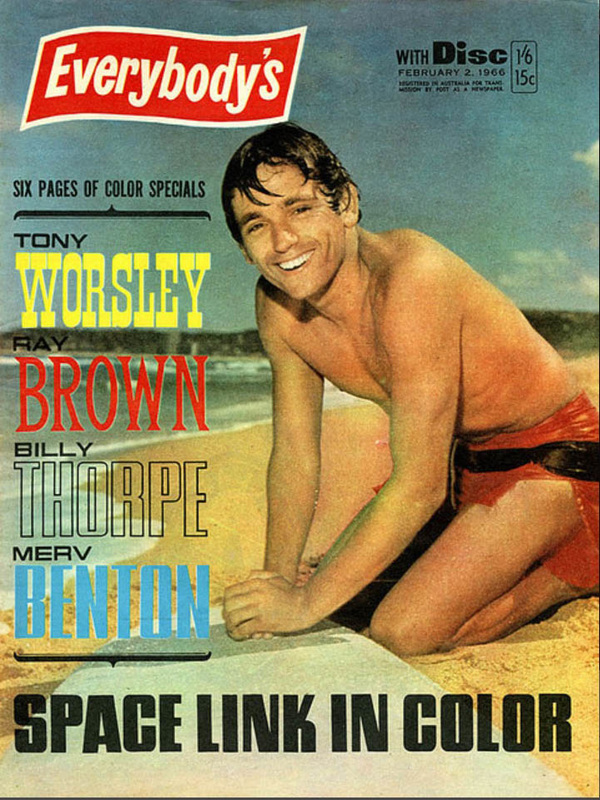

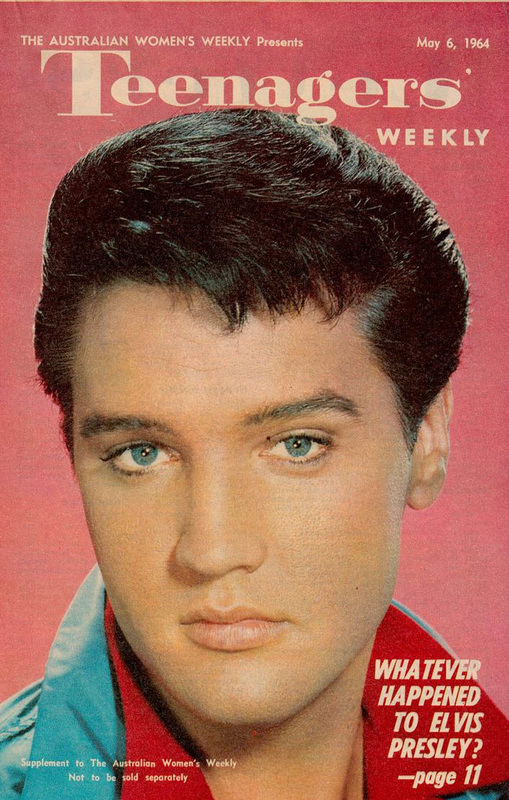

This was ground-zero for Australian rock writing, and it is remarkable how tied-up with ACP its infant development was. After Roxon left Sydney for New York in 1959, Donald Horne took over editorship of the Bulletin and he hired English emigree Charles Higham to review music and books. Higham actually didn’t condescend to rock’n’roll, even local rock’n’roll; you can read the Sydney Morning Herald's 2012 obituary of Higham here, though not unsurprisingly it overlooks his 'low' early work in Australian music. In 1961 ACP folded Weekend and launched, effectively in its stead, Everybody’s magazine. With writers like Jim Oram and Maggie Makeig, Everybody’s was an unabashed fan magazine with an emphasis on pop stars. ACP’s Woman’s Weekly took on the insert Teenager’s Weekly, and then Everybody’s added the Disc insert.

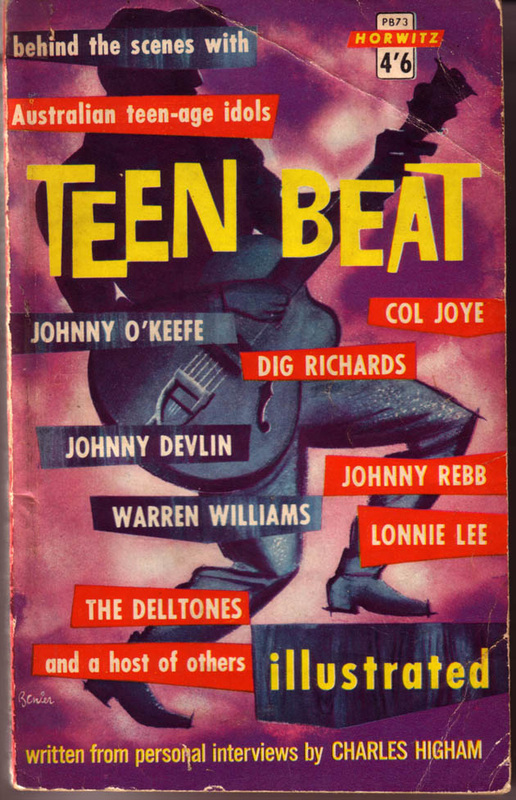

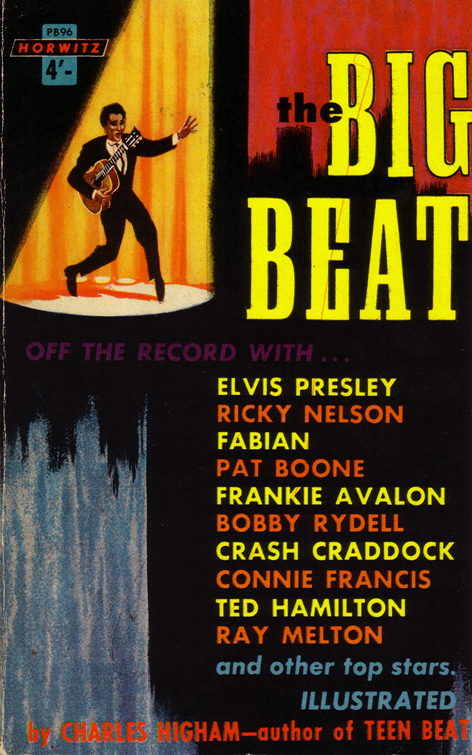

The first Australian rock book, Teen Beat, by Charles Higham, arrived in 1961, published by Horwitz. It was one of the world’s first rock books, following 1958’s Skiffle, by Brian Bird, out of the UK, and out of the US, Who’s Who in Rock’n’Roll, by Vic Fredericks. There was after that a few star biographies of the likes of Elvis and Cliff Richard, and then in ’61, Higham’s Teen Beat and The Big Beat ran parallel to couple of other fine prosopographies that came out of the UK, Royston Ellis’s The Big Beat Scene and Steve Kahn’s Tops in Pops (for a more-or-less full bibliography of the pioneering early days of rock books, go to these pages of mine here). |

|

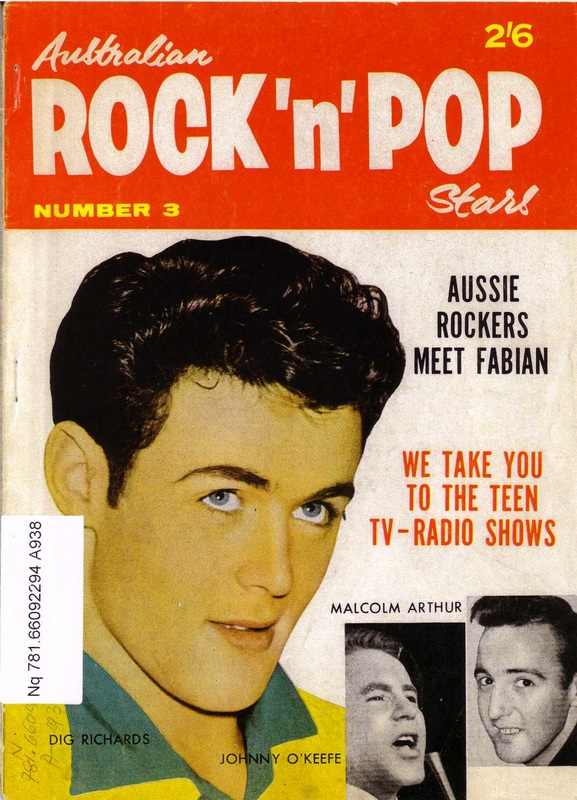

Like Who’s Who in Rock’n’Roll and The Big Beat Scene, both Higham's books were compendiums of portraits (prosopographies) of all the top American rock’n’roll stars, plus a few loose Australian ones. And so Ted Hamilton and Ray Melton share cover lines with Elvis, Fabian, Frankie Avalon, Crash Craddock and Connie Francis! Horwitz, of course, was no real legitimate publishing house but Australia’s pulp merchant supreme, purveyor of all things seamy and disposable, and if Australian rock books had to begin anywhere, it was appropriately here. Today, a good clean copy of Teen Beat might set you back $100. The cover is typically-pulp gorgeous and the content pretty good too, a series of well-written star profiles of Johnny O’Keefe, Col Joy and all the rest of them. Higham would go on edit an anthology of horror stories for Horwitz before moving to Los Angeles and writing a string of ultra-successful if often controversial Hollywood biographies, among them Errol Flynn and Howard Hughes.

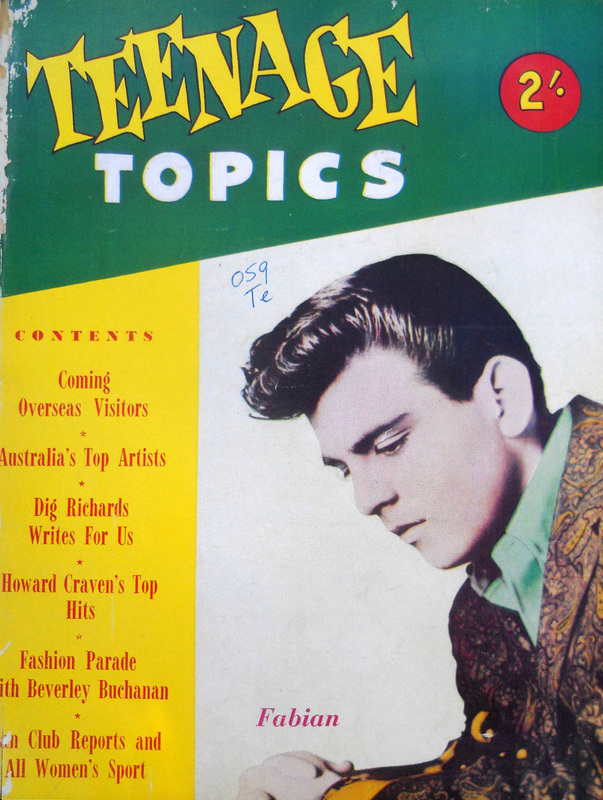

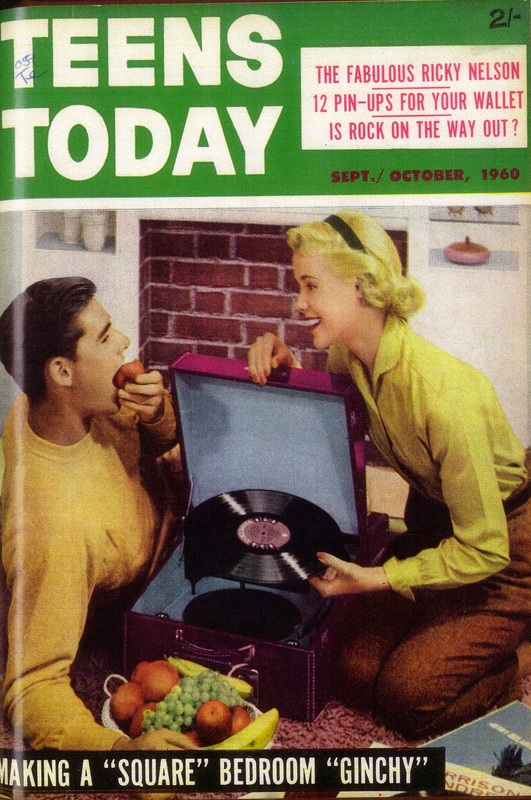

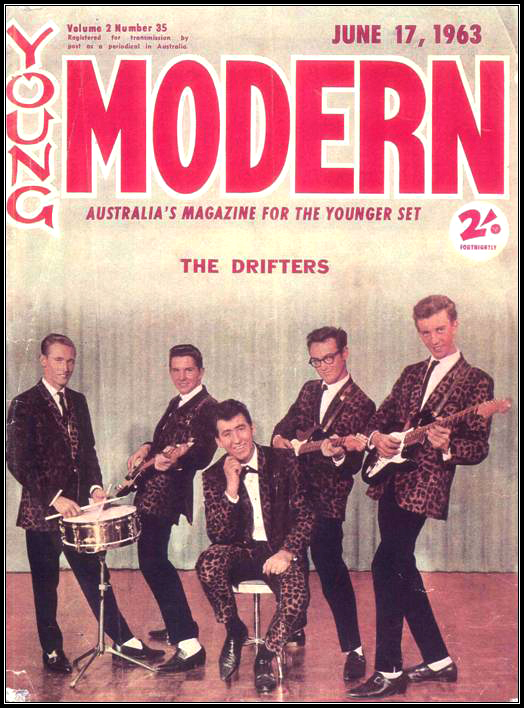

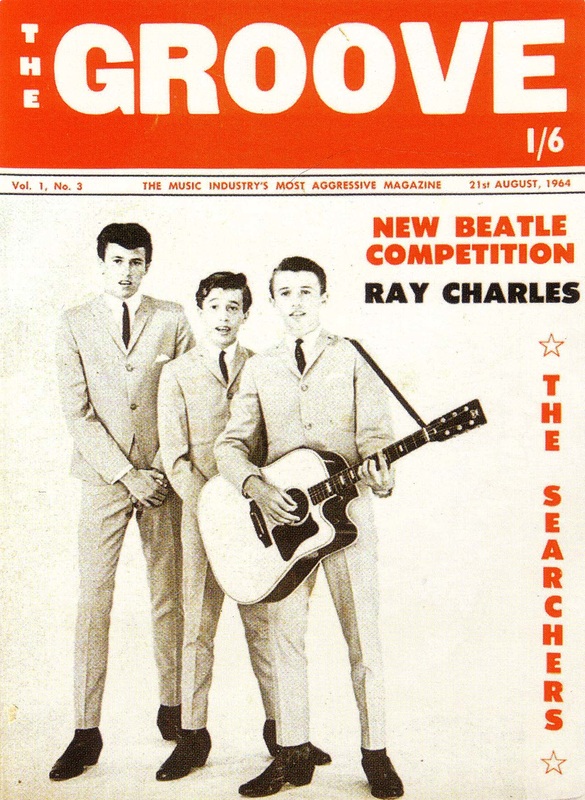

There is sometimes the perception that pre-Go Set the Australian rock press didn’t really exist. Magazines like Teens Today, Teen Topics, Fan Forum and Australian Rock and Pop Stars came and went around the turn of the decade, but at the same time, not only was there Everybody’s but there was also, out of Adelaide, the quite extraordinary Young Modern. Founded by local promoter Ron Tremain, it ran as a fortnightly for nearly a hundred issues between February 1962 up to June 1965, at which time it promised to be going weekly but seems to have instead folded altogether. |

|

Young Modern was a general youth-oriented magazine that in a reversal of usual form went from colour covers for its first couple of years to black and white. Some of its last issues featured covers on the Twilights for example, the first Adelaide band to break out nationally after the Penny Rockets never did. But it also did serious issues stories like about getting a job after getting out of jail etc. It expressed disappointment at the program for the first Adelaide Arts festival when it was announced in October 1963. See a bit more on Young Modern at the State Library of South Australia here.

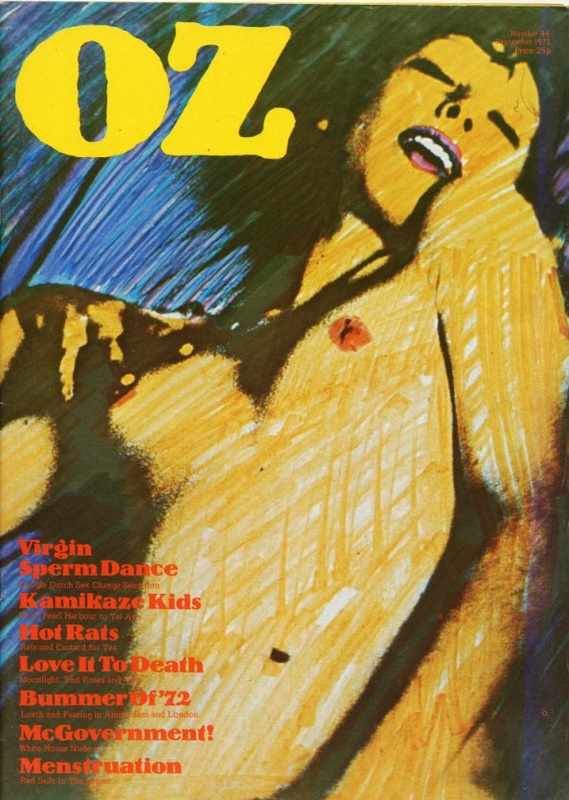

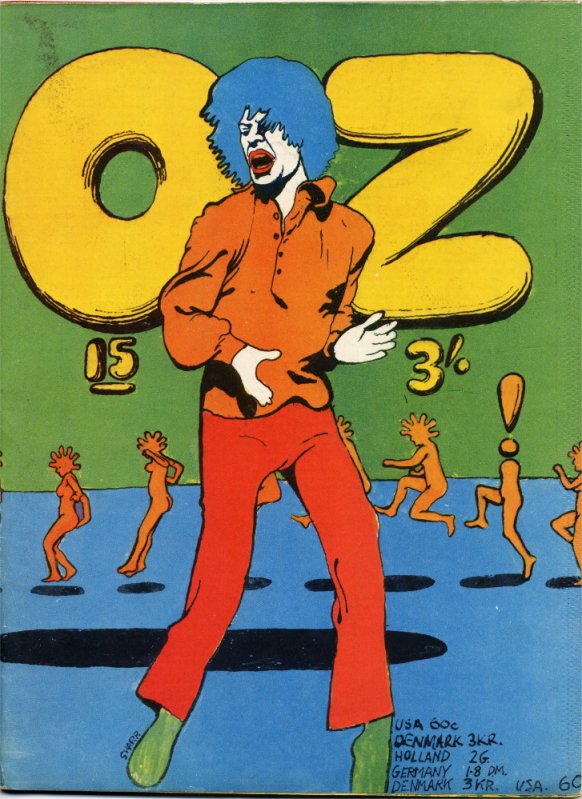

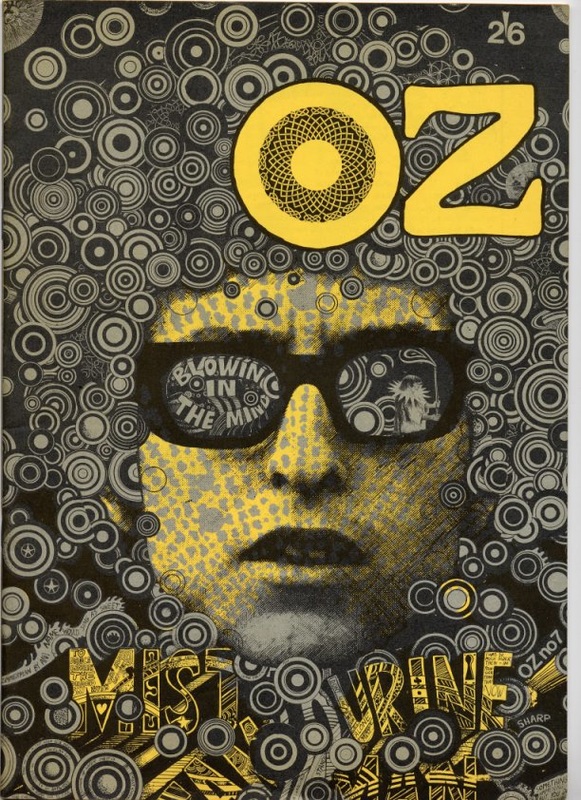

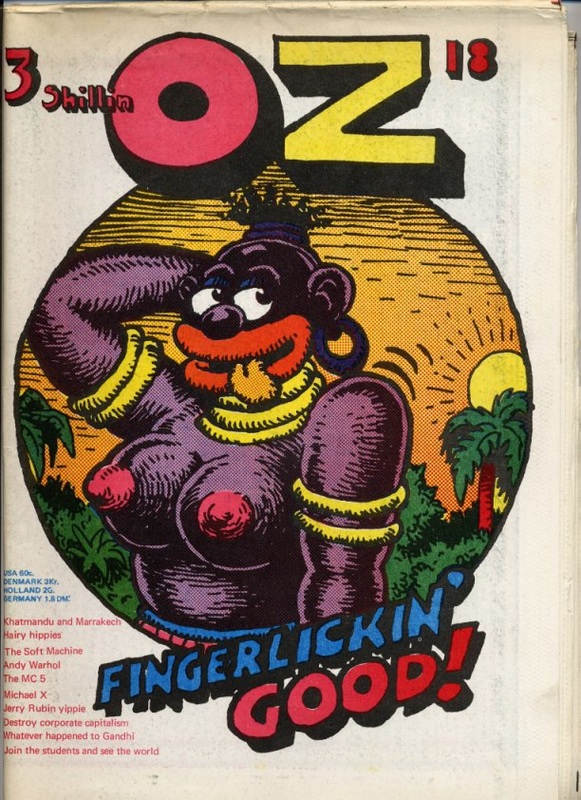

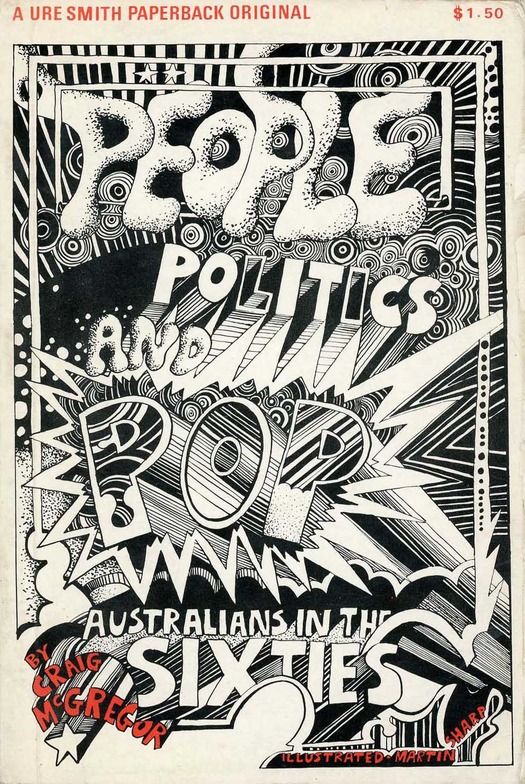

Another outlet that ran semi-serious coverage of rock’n’roll was Man magazine, for whom Robin Adair wrote some significant music stories. But with the Beatles’ first single coming out in Australia towards the end of 1962, the whole new order of rock’n’roll was about to be transformed again, and out of this would originate a sustainable tradition of independent music magazines. On April Fool’s Day 1963, Oz magazine was launched in Sydney by a consortium including Richard Neville, Martin Sharp and Richard Walsh, who’d been involved with university student papers like Tharunka and Honi Soit. But as much as Oz is today a publishing legend emblematic of 60s counter-culture, the magazine’s history has to be considered in two distinct phases – the first, coming out of Sydney between ’63 and ’66, and the second, based in London from ’67 up to the infamous obscenity trial of 1971 – and certainly, in its initial phase in Australia, Oz was chiefly satirical and had little time for rock music. As Craig McGregor quoted Richard Neville on the Beatles in his 1968 book People, Politics and Pop: “An asylum for emotional imbeciles.” But Neville changed his tune as soon as Oz arrived in London at the height of its Swinging in ’67 and saw how central pop was to the times’ broader social revolution. To see an extraordinary archive of every page of every issue of the Australian and London editions of Oz, go here and here. |

|

At that time, even overseas, underground publishing was only just beginning. The music scene was covered by existent trade papers and fan magazines ike Billboard, Hit Parader and Sixteen in the US, and Melody Maker and New Musical Express in the UK, who’d all adapted from Elvis to the Beatles. But it was the inception in the US of Rolling Stone in 1967 that changed or probably birthed the joint ideas of serious rock writing and underground publishing.

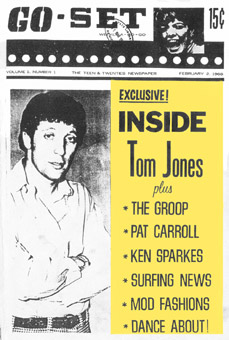

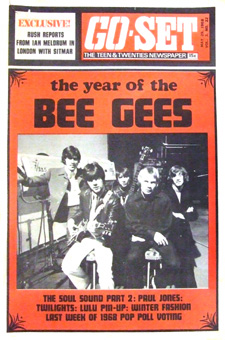

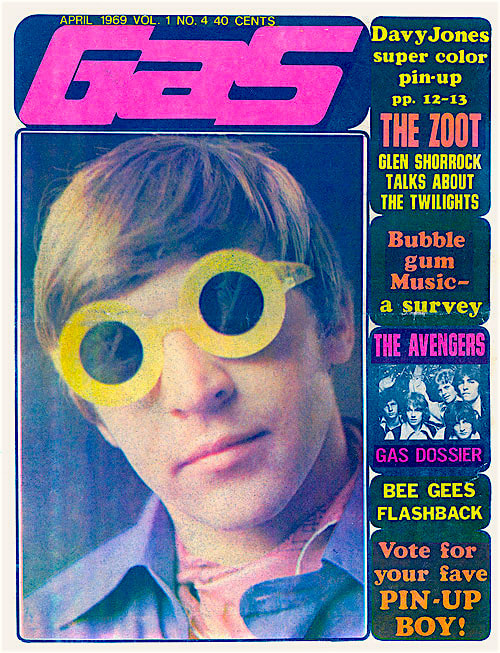

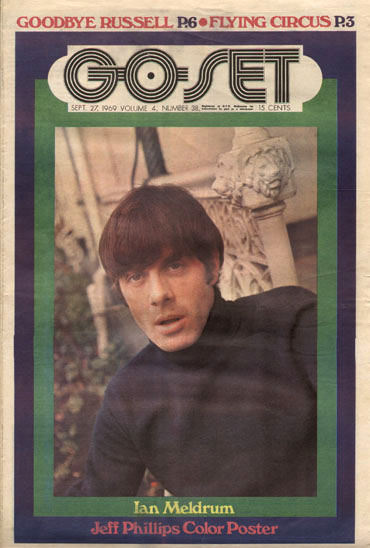

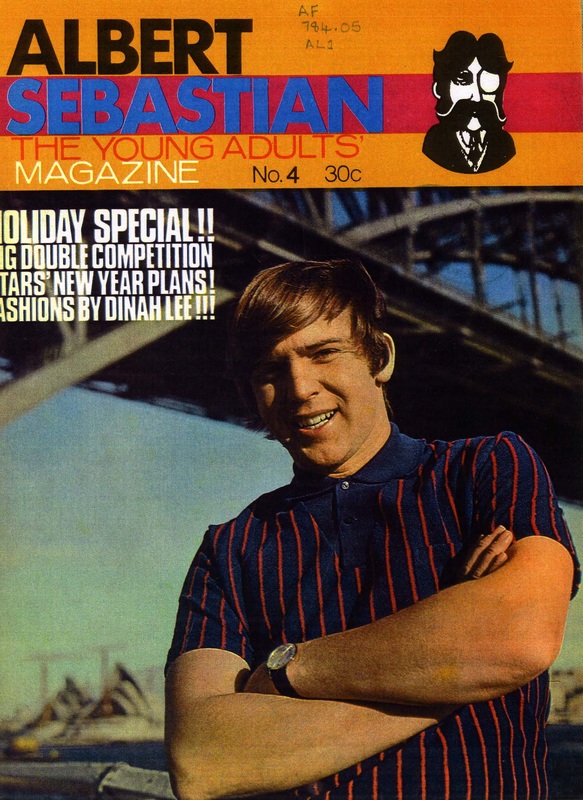

In Australia in 1966, as Oz was leaving the country to become a virtual journal of record in England, the magazine was born that would serve as the journal of record for Australian pop during the period, Go-Set. Launched out of Melbourne by another refugee from the student press, Philip Frazer, who’d worked on Lot’s Wife at Monash University, Go-Set was a hugely successful, national weekly tabloid that in many ways laid the foundations of the Australian music industry that still hold sway today. |

|

It’s probably true though that Go-Set’s most enduring quality is less in its writing, which was always very teenybopper-fannish even in the hands of a latter-day literati like Lilly Brett, than it was the work of photographers and designers like Colin Beard, Ian McAusland and Philip Morris. It was the long-standing Music Maker magazine, as it shifted from big bands and jazz to rock and jazz, that proferred some fine actual writing.

|

|

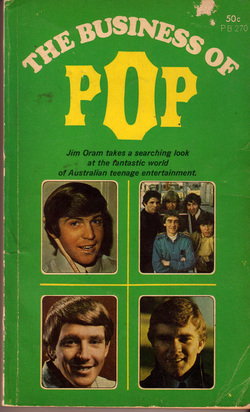

The third Australian rock book, Jim Oram’s The Business of Pop, was published in 1966, again by Horwitz. Like Higham’s Teen Beat and The Big Beat, it was a compendium of star profiles, now updated post-Beatles to feature the likes of Normie Rowe, Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs and the Easybeats. It sat semi-comfortably alongside pulp fiction titles on Horwitz’s list like Hoodlum, The Restless Ones, Wild Beat, The Rebels, My Boy George Rivers and Surfari Highway, all of which implicated rock’n’roll and even folk music in teenage delinquency. Oram would go on to legendary status as one of the last great larrikins of Australian journalism, with his own Walkley award named after him. The Business of Pop remains an illuminating glimpse into a nascent industry/culture.

|

|

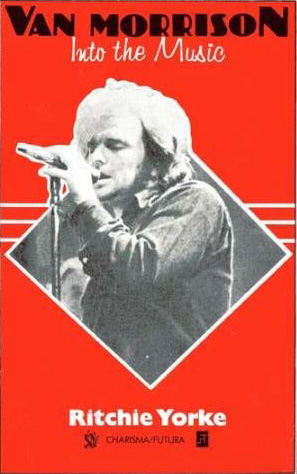

Two other writers published music related books in the 60s. Ritchie Yorke was a Brisbane cadet journalist who in 1967 knocked out a quickie pocketbook called Lowdown on the English Pop Scene for Australia’s other great pulp merchant, Scripts. Craig McGregor, who started out as a sort of token long hair/social chronicler at the Sydney Morning Herald, in ’68 published People, Politics and Pop through long-standing art-house, Ure Smith; the book was shot through with music and intimations of the counter-culture to come, but McGregor, an intellectual and surfer, seemed to prefer folk and jazz to rock.

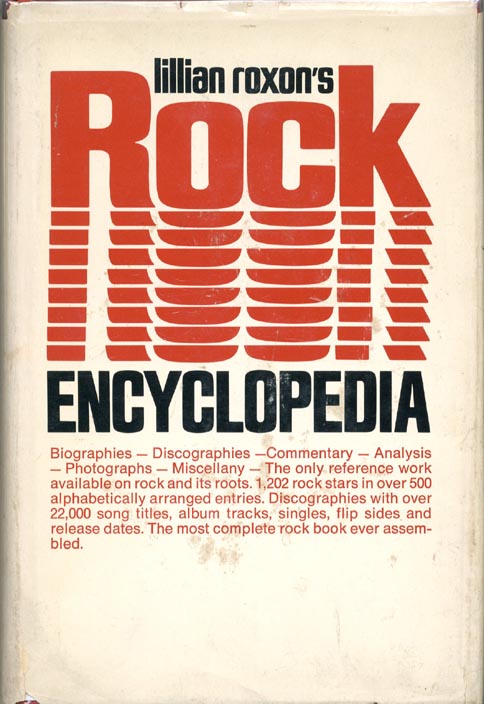

But like all the Australian bands who won the annual Hoadley’s Battle of the Sounds and dutifully boarded ships like lemmings bound for the real big game in London, the exodus was also on among the best young rock writers, as Yorke and McGregor followed Roxon and the Oz crew overseas. And it’s probably fair to say the writers fared better than the bands, most of whom sooner or later limped home with their tails between their legs. The tone was set, of course, by Lillian Roxon, and crowned in 1969 when she published Lillian Roxon’s Rock Encyclopaedia. The self-styled Dean of American Rock Critics, Robert Christgau, in 2004 called Roxon “insufficiently legendary,” but doubtless he was unaware of Robert Millikin’s 2002 Roxon biography Mother of Rock, which put her on par with the only other rock journalist to have had a book written about him, the doyen, the late Lester Bangs. If she has been neglected at all it’s less likely because she was a woman (since other pioneering female music writers like Gloria Stavers, Ellen Willis, Lisa Robinson, Val Wilmer and Caroline Coon are well recognized), than because she was Australian. Roxon is the embodiment of early rock journalism on an international as well as Australian level. Possibly all she was ever trying to do was live up to her perfect name – Lillian Rocks On! She started out as a bit of a folknik at Sydney University in the 50s, but had her head turned not so much by Elvis or the Beatles as Australia’s own Easybeats. But as even Milliken gets wrong, our Lill’s encyclopaedia was nowhere near the first serious book about rock. Millikin cites four other titles as having been among the first in 1969, when John Gabree’s The World of Rock from the year before was one among a few in the late 60s, and ’69 itself saw a whole slew of books (including Carl Belz’s The Story of Rock, Paul Williams’ Outlaw Blues, Greil Marcus’s Rock Will Stand, Jonathan Eisen’s The Age of Rock, Dave Laing’s The Sound of Our Time, Derek Johnson’s Beat Music, Nik Cohn’s Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom, Arnold Shaw’s The Rock Revolution and Ralph J Gleason's Jefferson Airplane & The San Francisco Sound. Hunter Davies’ biography The Beatles had come out the year before, and Richard Meltzer’s The Aesthetics of Rock and [Richard] Goldstein’s Greatest Hits, among quite a few others, would follow in 1970. For a full overview, see, again, my Rock Ink pages here). Gabree’s 1968 Fawcett paperback was a reasonable stab at a potted history of rock and pop, even if the author himself seems a bit surprised to be there at all. “Perhaps the strangest development over the past two or three years,” he writes, “has been the growth of serious rock criticism.” Lillian Roxon’s Rock Encyclopaedia was nonetheless groundbreaking as a type of codification of serious rock criticism, and it was charmingly-written, and certainly it was the first of a number of important books by expatriate Australians. It’s just a shame that Mother of Rock was barely the biography Roxon deserved; so bloodless was it that when ABC-TV produced a documentary of the same name in 2010, it was based less on Robert Milliken’s book itself than my review of it, which was published in the Sydney Morning Herald - read it here - and was in essence and some detail a corrective that the film followed. |

|

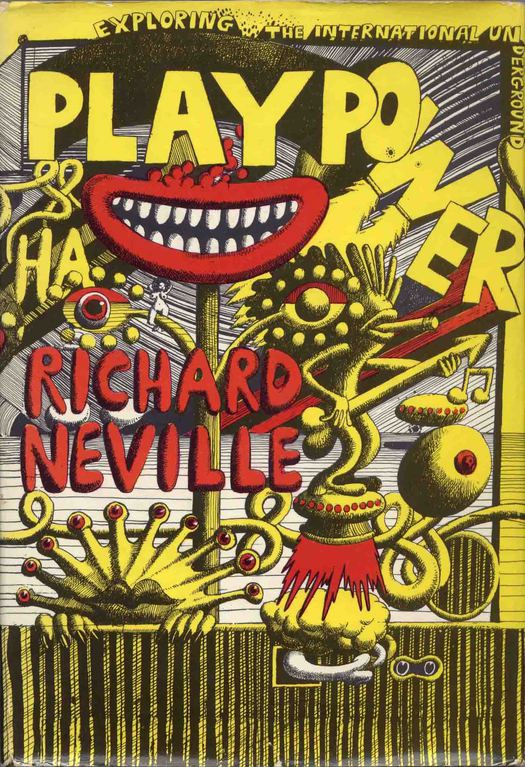

Richard Neville was the next cab off the rank, when he published Play Power in 1970, a collection of his Oz journalism. But as much as its significant musical content painted an evocative picture of the late 60s’ London rock scene, for Australian readers there was a whiff of the cultural cringe about it. As if Australian pop was not quite good enough.

Ritchie Yorke had left Brisbane in 1968 when, as an agent for promoter Ivan Dayman, he took Normie Rowe to London. When Rowe returned home (only to be called up to serve in Vietnam), Yorke moved on to Canada, where he resumed writing and became, famously, one of John Lennon’s peace envoys. In 1971 he published what was one of rock’s first regional histories, Axes, Chops and Hot Licks, about the Canadian scene, and he would go on to publish three other important books in the 70s, The History of Rock’n’Roll in 1976, and biographies of Van Morrison (1975) and Led Zeppelin (1976). Only recently has he finally (self) published a memoir of his time working with Lennon, called Christ, You Know it Ain't Easy. Craig McGregor went to New York on a Harkness Scholarship and as a consequence of that, he edited the pioneering Dylan: A Retrospective, which, published in 1972, sat alongside Toby Thompson’s Positively Main Street as one of the early entries the now-vast bibliography of Dylanology. McGregor also wrote Up Against the Wall, America, which was published by Angus & Robertson in Australia in 1973 and contained, along with a number of great music pieces, mainly on blues artists, a profile of Lillian Roxon, which would take on extra poignance when she sadly died later in ’73. It also contains his damnation of the Beatles that prompted John Lennon to pen and angry letter of reply. These writers took a global view even before there was much of a local one. Maybe the men were just trying to dodge the draft. But back home a tangible counter-culture was just being born at the same time, and this would trigger a re-start for a more indigenous tradition in Australian music writing. |