5: CULTURAL REVOLUTION

|

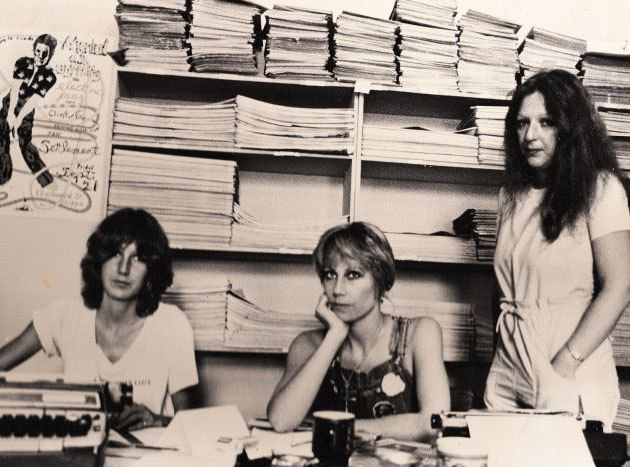

In Australia in the early 70s the underground press was properly born, and the dominant figure would remain Philip Frazer.

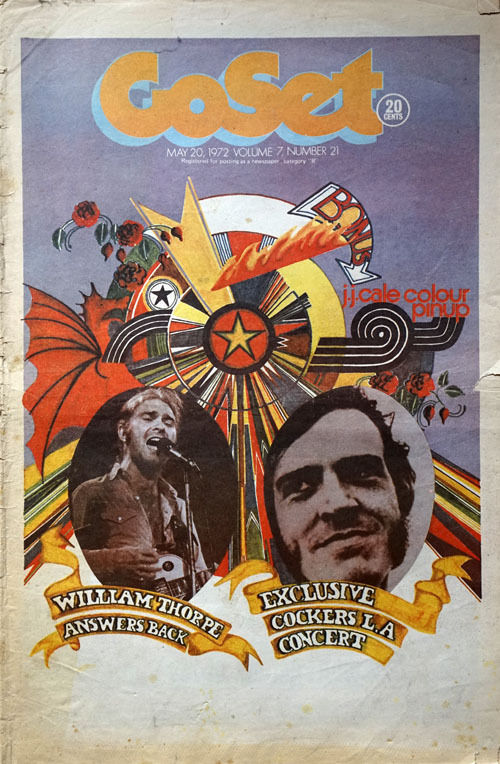

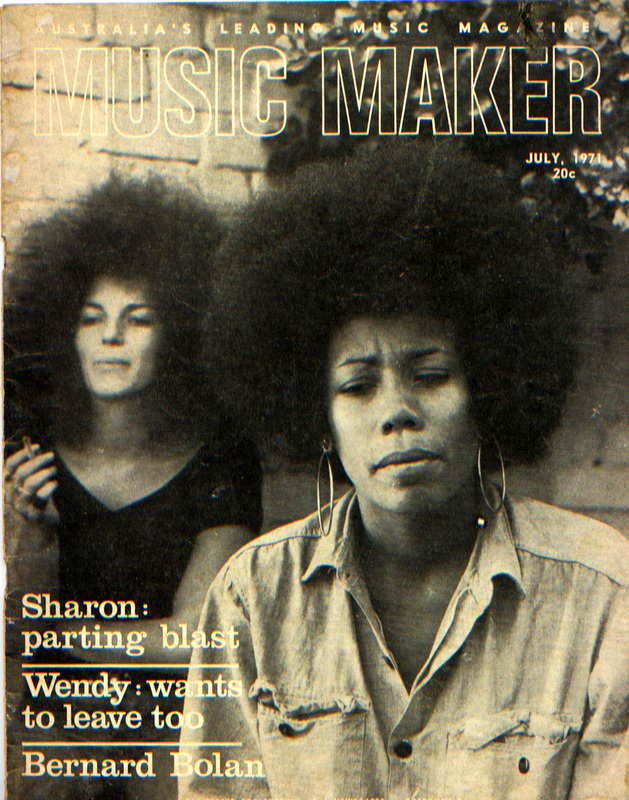

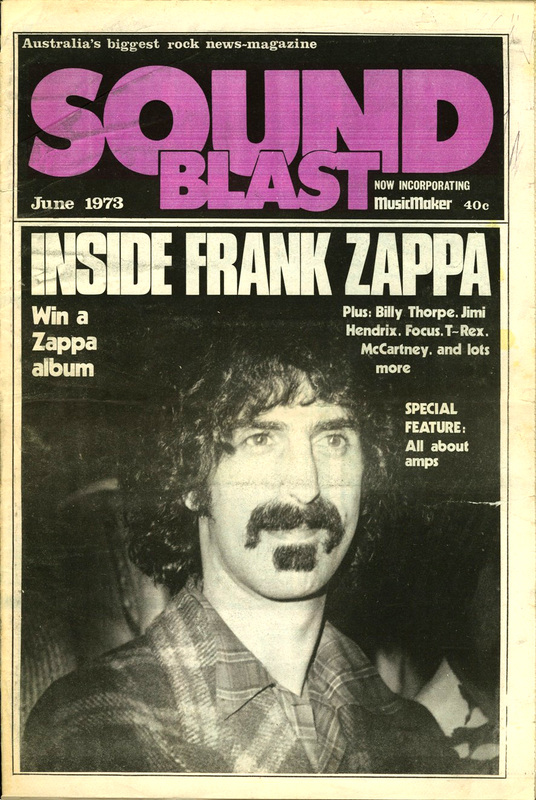

When Gough Whitlam was elected Prime Minister in 1972, ending two decades of conservative Liberal Party rule, it was a mark for Australia of a new youthful liberalism and confidence. When he was controversially sacked from office as soon as 1975, it was as if the whole 60s/hippie dream was finally killed off. It was a short-lived Garden. But the Australian cultural renaissance of the period left a profound legacy. There was a time in the early 70s when you could have picked up almost concurrent issues of magazines like Go-Set, SoundBlast, (Daily) Planet, The Digger, Gas, High Times, Ear for Music, Tracks, Rolling Stone, Living Daylights, Oz, even a revitalized Music Maker under editor John Clare, and an Australian accent was leaping off the page. Rob Smyth was writing for the Nation Review. A genuine Australian blues-rock sound was emerging too in bands like Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs, Daddy Cool and Chain, and original songwriting was rapidly developing especially in country-folk-rock acts like the Flying Circus, Axiom, Country Radio and the Dingoes - and all these were hitting the top of the singles charts as well as the newly-convened album chart. Australia didn’t get albums charts till 1970, when Go-Set introduced them. Along with the inception of ABC-TV show GTK around the same time, and of the Sunbury festival in ’72, these were the totems of a whole new era. |

|

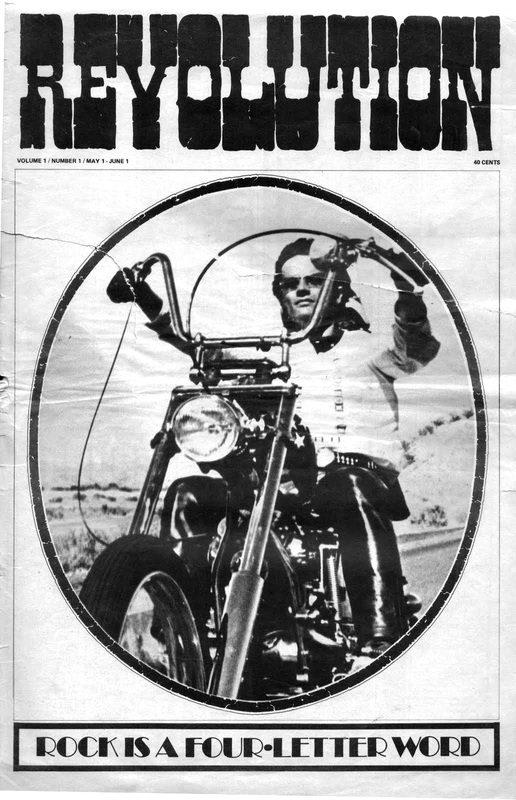

Philip Frazer had seen the storm clouds coming. The teen-scream tone of Go-Set was rapidly seeming immature towards the end of the 60s. The magazine’s domination was so complete that Frazer was forced to compete with himself, launching on one hand in 1969 a new title called Gas, for the ultra-teeny-boppers, and on the other, a rag for the hippie market, initially a Go-Set insert called Core but soon the standalone Revolution. Revolution carried an insert of its own being a cut-down edition of American Rolling Stone. Frazer had connected with Stone founder Jan Wenner in San Francisco and secured the local license on a handshake and a joint. With the sexual revolution, a booming economy, resistance to the Vietnam war growing and the imminent election of Gough Whitlam, there was a feeling in Australia that anything was possible.

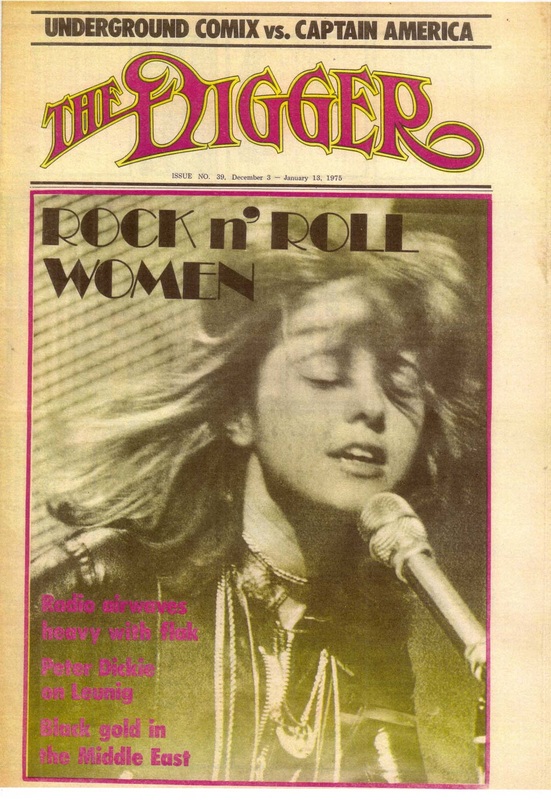

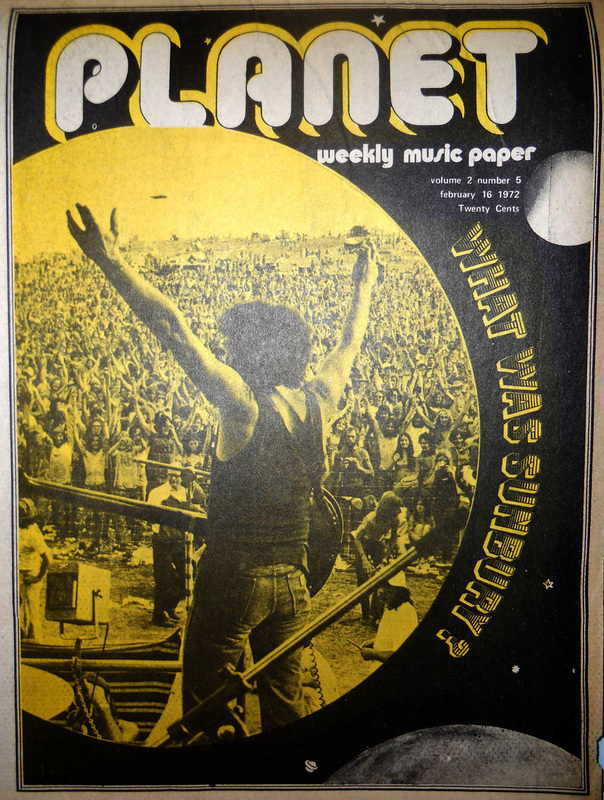

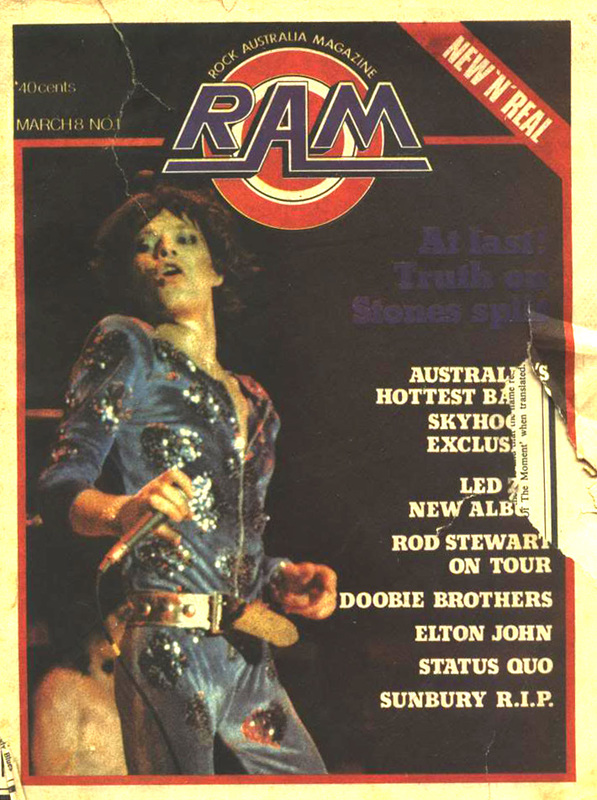

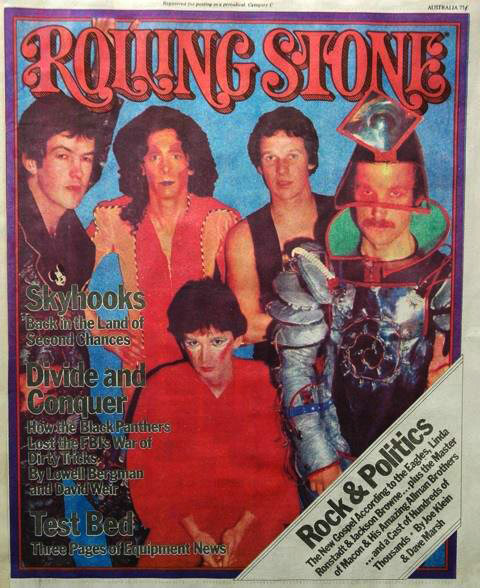

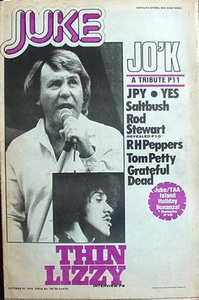

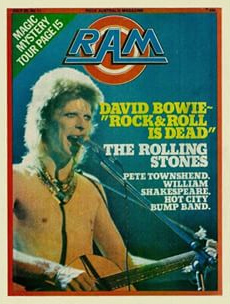

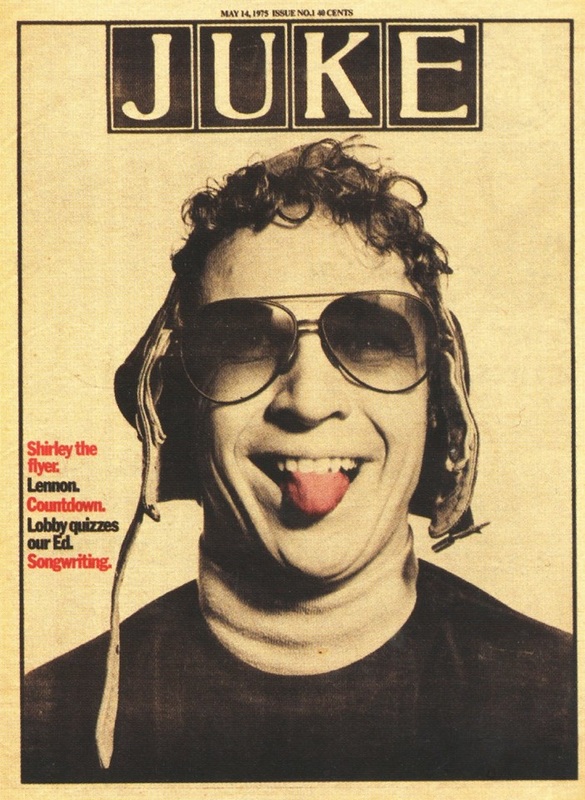

In ’72, Frazer traded off Go-Set for its debt to its printer, killed off Revolution, and launched, jointly, a standalone local edition of Rolling Stone and an all-new Australian title called the Digger. The Digger became a publishing legend. Over the course of just 48 issues it introduced such writers Helen Garner, Colin Talbot and Garrie Hutchinson (who would go on to revolutionise sports journalism in Australia with his football writing in the 80s, which had a real effect on me among many others), and published so many others like Robert Adamson and Frank Moorehouse. Frazer’s closest rival - not that it was very close - was the Daily Planet. Launched in ’72 by the Melbourne music mafia soon to coalesce under Michael Gudinski as Mushroom Records, the Planet was a forerunner to today’s free street press, edited by guitar hero Lobby Loyde. Go-Set was kept alive by new editor Ed Nimmervoll, but when it moved to Sydney at the end of ’73, to be absorbed into the English publishing empire IPC (which also owned Melody Maker and the NME), that was the real beginning of its end. By the end of 1975, when Whitlam was sacked, not only was Go-Set finally dead but so were all these other markers of an era – the Digger, GTK, Sunbury, the Planet, even Music Maker folded after forty years. Doubtless this was concomitant to the fact that the bands had quickly faded too, like classic one-hit wonders. Philip Frazer killed off the Digger (its final issue carrying an ad for “the Last Reefer Cabaret” in Melbourne, starring Ayers Rock, Renee Geyer, Split Enz, Captain Matchbox, Ariel, Chad Morgan and Geoff Duff), and he sold the local Stone license to a new consortium from Sydney. He left the country to go and live in New York, where he worked for many years as a media specialist before recently returning to Australia to retire. The remnants of Planet and Digger got together to mount Loose Licks, but it didn’t last long. It was already a different age. But it was seeds sown in the early 70s that would blossom in the second half of the decade. The last Sunbury festival, headlined by Deep Purple, was held over the Australia Day long weekend of 1975. Within weeks, a whole new musical order was jostling for position. The ABC launched Countdown as a new pop show on now-colour TV screens, and it launched radio station 2JJ in Sydney as a forerunner to today’s “national youth network.” Also, new rock magazines RAM and Juke were launched, along with the reborn Sydney-based Australian Rolling Stone. After all the turbulence and come-and-go start-ups of the early 70s, these three magazines would be extremely stable and along with Countdown, would all flourish until well into the 80s. |

|

So much changed in 1975. FM radio was introduced, leading on one hand to the tighter formatting of commercial stations and on the other, to the street-level of public broadcasting.

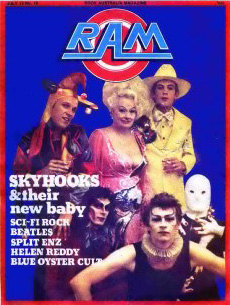

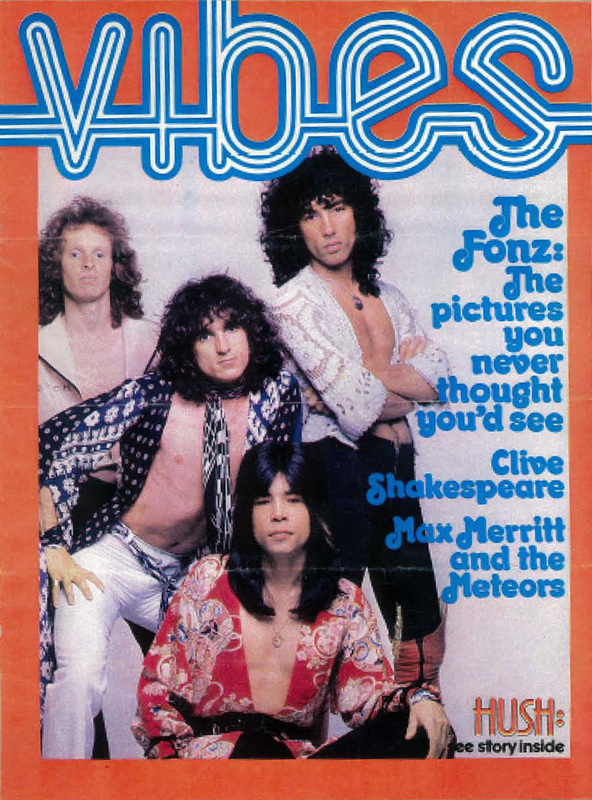

Countdown, in a way, was Australia belatedly getting glam rock, with its new young stars like Skyhooks, Sherbet, John Paul Young and AC/DC, and its even-then old host, Molly Meldrum. As soon as Molly got on the screen, he got a ghostwriter for his TV Week column. The teenyboppers had plenty of their own glossies too, like Spunky!, Vibes, Scream! and others. |

|

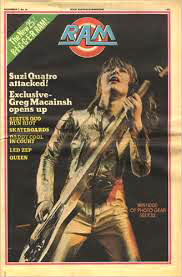

If there was a direct line through Molly from Go-Set to Countdown, there were lines leading directly from Go-Set to RAM and Juke too. RAM was the brainchild of publishers Philip Mason and Barry Stewart; Mason was a former IPC executive who'd come out to Sydney from England to help launch Dolly, the magazine for teenage girls that drove the last nail in Go-Set’s coffin. Joining forces with numbers man Stewart, Mason and he saw the opening for a new rock rag, and picking up IPC's old Australian reprint rights to Melody Maker and NME, they hired Anthony O'Grady as editor on the still-as-yet unnamed title. O'Grady was a sometimes advertising copywriter who'd edited a short-lived glossy called Ear for Music in ’73, and occasionally contributed reviews to the equally shot-lived SoundBlast. They christened the new rag Rock Australia Magazine, or RAM, and launched it as a fortnightly tabloid foldover with a colour cover. RAM was an immediate success, and Soundtracts Publishing, which was eventually re-named Mason-Stewart, expanded with the acquisition of surfing bible Tracks, which it bought off originators Albie Falzon and former Go-Setter (and later film-maker) David Elfick, and with the launch of fashion mag Ragtimes. Anthony O’Grady’s avowed ambition was to ensure there was no quality drop between RAM’s local and imported copy, and this he achieved in a sustained way that nobody had quite ever pulled off before. AO'G, in many ways, is the real great godfather of Australian rock writing to whom so many, myself included, will always be indebted.

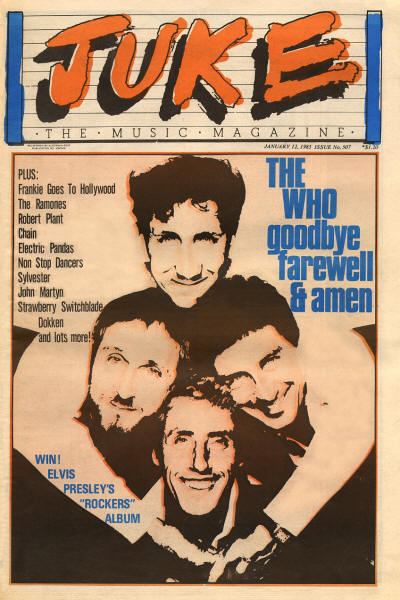

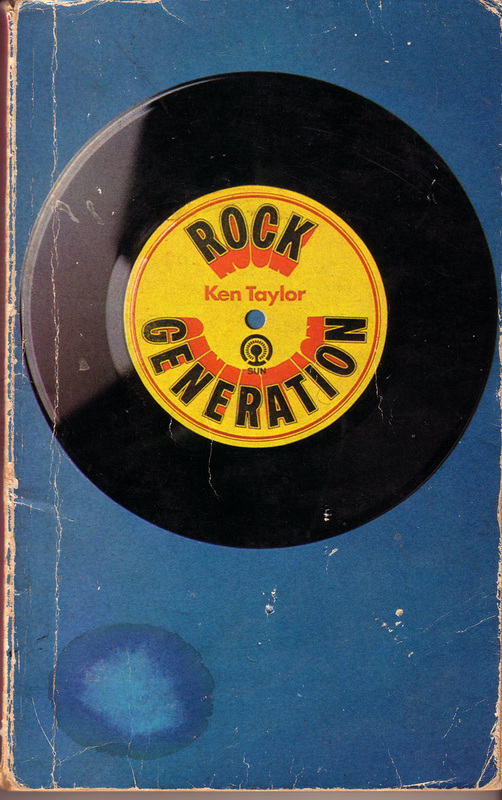

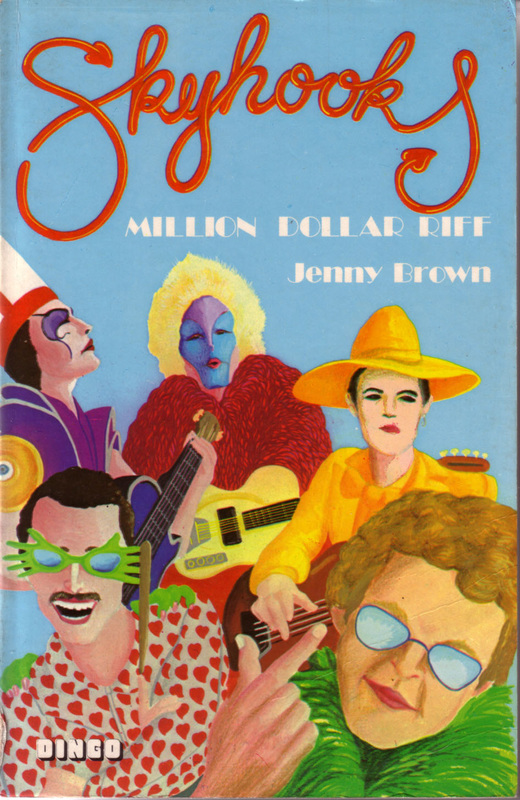

Juke was launched out of Melbourne by Ed Nimmervoll, who picked up the reprint rights to new English weekly Sounds, and did a print-distribution deal with Age-owner David Syme. But with its indisputable Melbourne-centricity, not to mention tardiness to embrace changes in music, Juke struggled for credibility on a national level. Rolling Stone, which had been taken over from Philip Frazer by former Financial Times journalist Paul Gardiner, immediately stepped up both the quantity and quality of its local content. But there’s no doubt that RAM, in the mid-to-late 70s at least, really led the way. Skyhooks’ Greg Macainish had shown it was possible to write pop songs with an Australian accent, with our references and vernacular language, and even lowly local rock journalists were not immune to the excitement of the possibilities this opened up. In 1975, there were three other releases of great significance to the literature of Australian music, two books that broke the local drought in force since former Festival A&R manager Ken Taylor’s 50s’ memoir Rock Generation in 1970, and a compilation album Glenn A. Baker produced (through Festival Records) called So You Wanna Be a Rock’n’Roll Star. Jenny Brown’s book about Skyhooks, Million Dollar Riff, published by Dingo Press, was a first as a band biography, and it was enhanced by the wonderful photographs of the late, great Carol Jerrems. Sydney radio DJ Bob Rogers’ illustrated personal history Rock’n’Roll Australia: The Australian Pop Scene 1954-1964, was amiable enough too. But it was Glenn A. Baker’s double-album anthology of 60s Australian bands, complete with extensive liner notes, that first espoused a sense of local rock as aesthetic and social history. |

|

It’s another classic rock journalism syndrome too, that Baker did his important early work not even so much through magazines, let alone books, but through the unique sub-genre of liner notes. Liner notes first came into their own as part of the extremely elegant packaging added to jazz albums in the 1950s. Pop records might have offered some fluffy hype on the back cover, but the sort of reportage and analysis that jazz critics went for was, in fact, one inspiration that rock journalism followed. But liner notes took on another dimension when applied to archival reissues. Musicologist-mystic Harry Smith almost single-handedly triggered the folk revival with his monumental Anthology of American Folk Music from 1952, and when rock critic and future Patti Smith guitarist Lenny ‘Doc Rock’ Kaye put out his Nuggets double-album of 60s American garage bands in 1972, he did something similar for punk rock to come; certainly, he inspired Glenn A. Baker, and not only him but others like myself too. Baker’s breakthrough was to recognize the history in our own backyard. After a second double-album volume of So You Wanna be a Rock’n’Roll Star in 1978, Baker would go on to release a stream of reissue albums (eventually through his own label Raven Records) which together, with their liner notes, constitute an epic, discontinuous narrative.

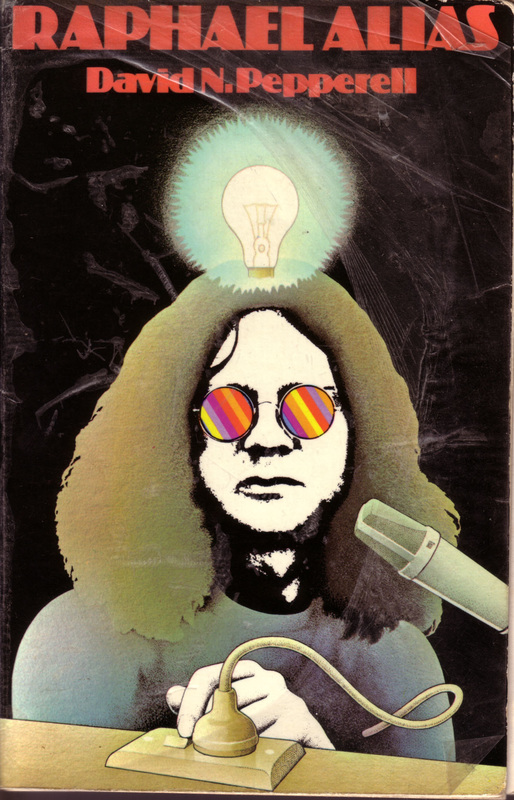

Outback Press was formed in Melbourne as a partnership between Colin Talbot and Morrie Schwartz (presently owner of the Black Inc/Monthly publishing empire), and in 1976 it put out The Bumper Book of Rock, a photographic collection by Philip Morris with words by Martin Fabinyi. Outback also published Raphael Alias, an anthology of journalism, rock criticism and poetry by David Pepperell, aka Dr Pepper, a regular contributor to the underground comix and co-proprietor of one of Australia’s first import record stores, Melbourne’s Archie & Jugheads, soon to become Missing Link under the sole tutelage of Keith Glass, who himself was a writer of some note too, as well as a musician and producer. Talbot split bitterly with Morrie Schwarz and he went to Wild & Woolley to publish his collected journalism, Colin Talbot’s Greatest Hits, in 1977. Wild & Woolley was a partnership between writer Michael Wilding and American emigree Pat Woolley, who’d worked with Philip Frazer briefly on a local edition of High Times magazine. Talbot’s book was an Australian breakthrough linking rock and gonzo. His subsequent drift into fiction and poetry was, to me, less satisfying. Outback Press went on in 1978 to publish Noel McGrath’s Australian Encyclopaedia of Rock and Pop. It was so successful that in ’79 they followed it up with a Yearbook, although that wasn't enough to prevent the company from soon enough folding. Local rock journalism was now armed with a basis of science and art, a sense of history, but perhaps more importantly, the sense that history could also be happening right now, which is what gives the form one of its great strengths, its urgency. RAM and Countdown succeeded because even as the mid-70s glam rock bubble pretty quickly burst (with really only AC/DC surviving, by escaping overseas), it was already being superseded by Sydney pub rock, the emergence of bands like Cold Chisel, Midnight Oil, the Angels and Rose Tattoo. And it was the sustainability of this wave, in contrast to the one-hit-wonderdom of the early 70s proto-pub rock, that provided RAM especially with such great fodder for its writers like O’Grady himself and not only Annie Burton, Jenny Hunter-Brown (as she was then known) and Andrew McMIllan but also Miranda Brown, J.J. (Jodie) Adams, Greg Taylor and Stuart Coupe. |

|

Of course, barely as soon as pub rock was finding a footing in the late 70s, along came punk rock to spit in its face. Which I suppose I have to admit is about where I came in. But even as punk’s DIY ethic inspired another boom in underground/independent publishing, from fanzines to books and new magazines, RAM and to an increasing extent Rolling Stone stayed dually on top because unlike Juke, or Countdown for that matter, they were open to and integrated the new wave with the old. |