6: revolutions by the decades: d.i.y-2- c.d.

|

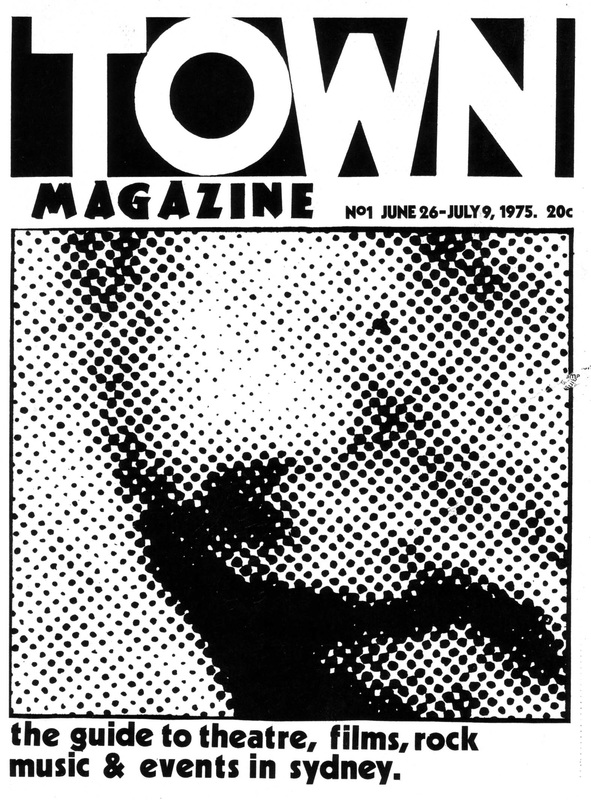

Punk inspired the first fanzines in Australia in 1977, after the model of England’s Sniffin’ Glue moreso than American Greg Shaw’s more seminal Who Put the Bomp? The first was probably Bruce Milne’s Plastered Press, whose one issue from ’77 was so homemade it wasn’t photocopied, but printed on an old Roneo mimeograph machine. I started doing one too, with Andrew McMillan, before moving on to collaborate with Bruce Milne on an intercity Melbourne-Brisbane superzine called Pulp. Ian Hartley in Sydney, who’d worked on the short-lived Town giveaway, put out the beautifully designed Spurt. Others were popping up all over the country: Self-Abuse, the Rat, Remote Control, Street Fever, Autopsy, DNA, Choke, Road Traffic Control. To see much more on the Australian punk-era zine scene, go to my dedicated page here.

|

|

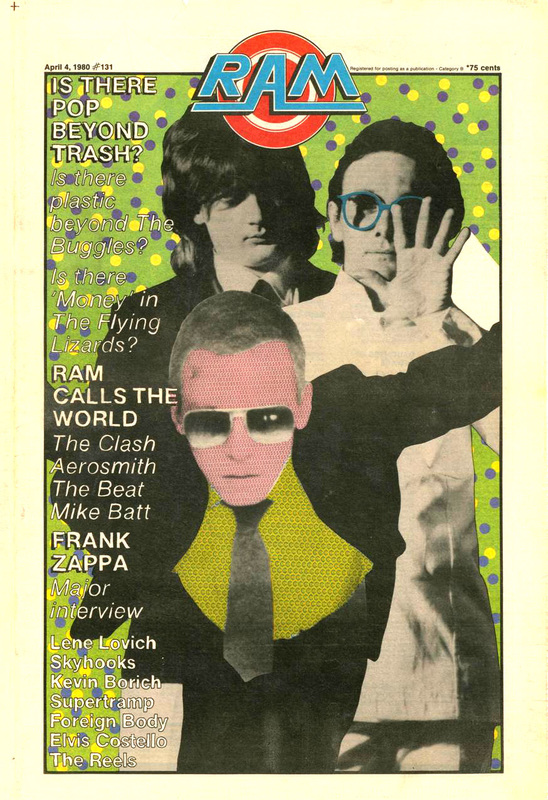

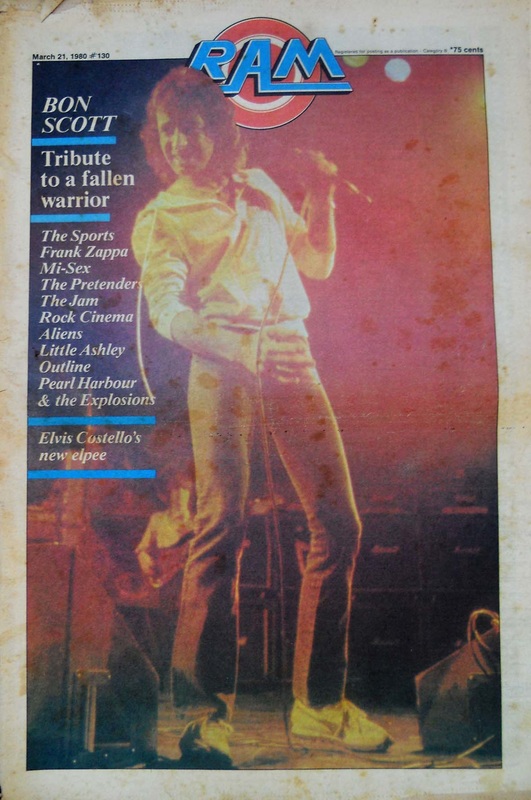

Punk, of course, caused a huge schism in music. At first, for RAM at least though, while Juke remained in the thrall of whatever Melbourne mafia don Michael Gudinski was dishing up that week and Rolling Stone remained in the thrall of the West Coast sound, it meant only that whilst local cover stories had to be hot-sellers like Chisel or Dragon, there might still be a Radio Birdman or Saints feature inside.

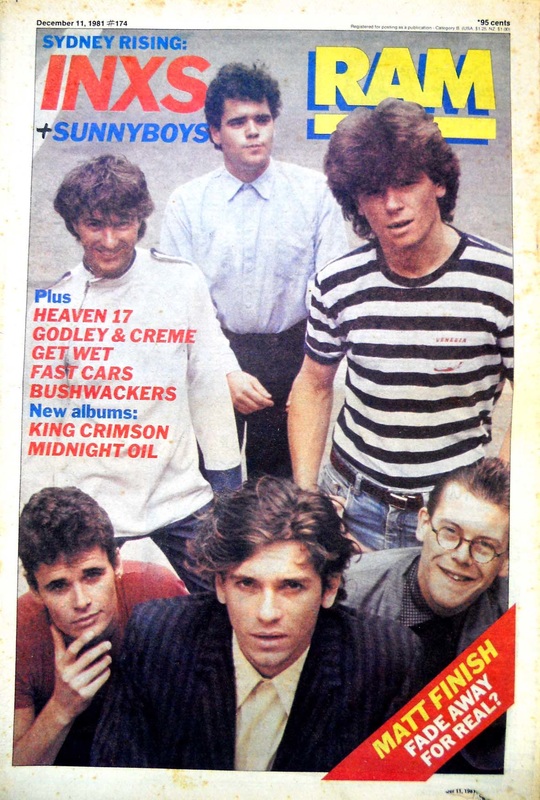

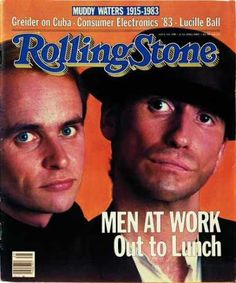

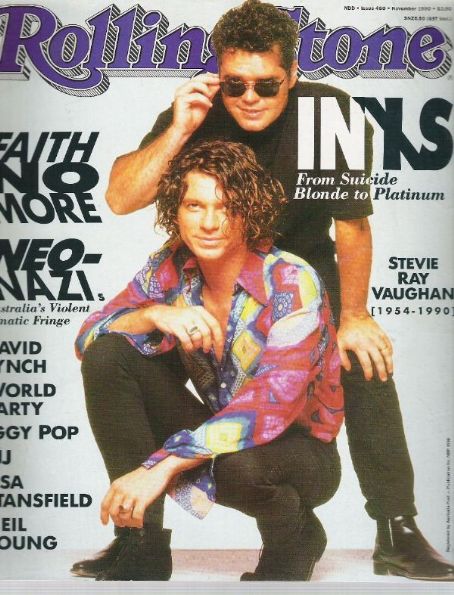

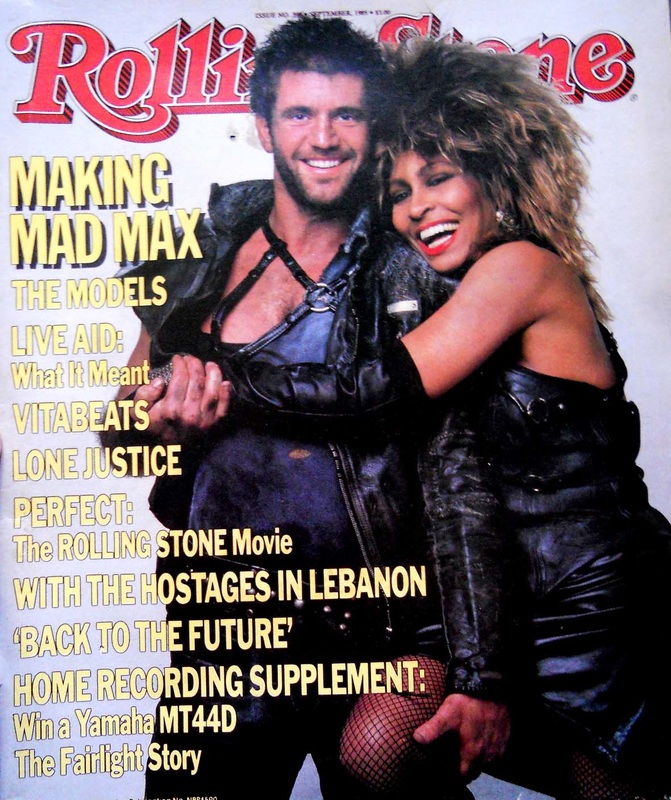

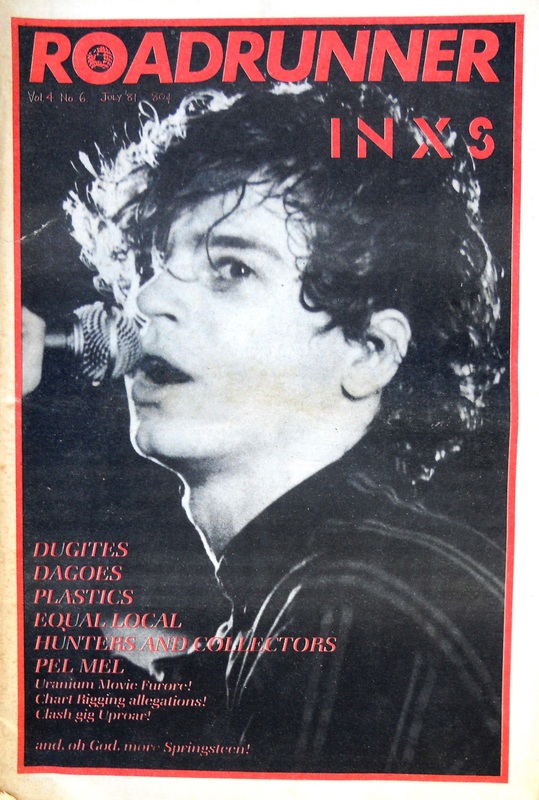

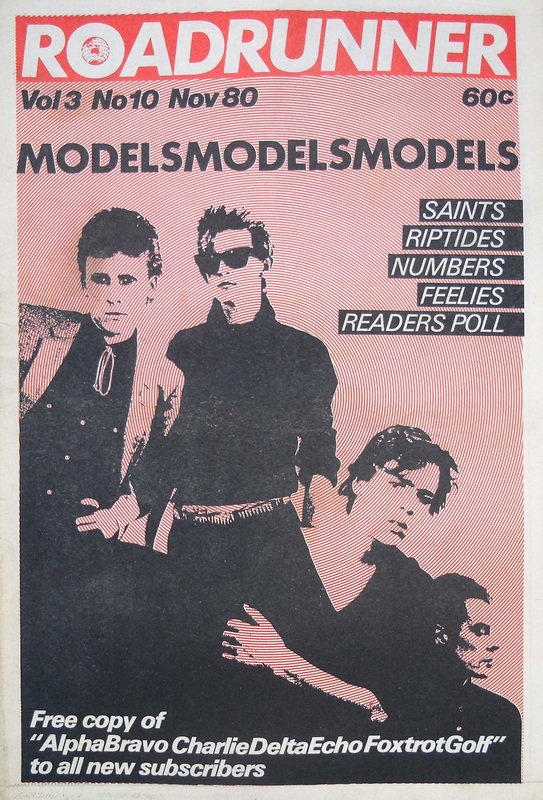

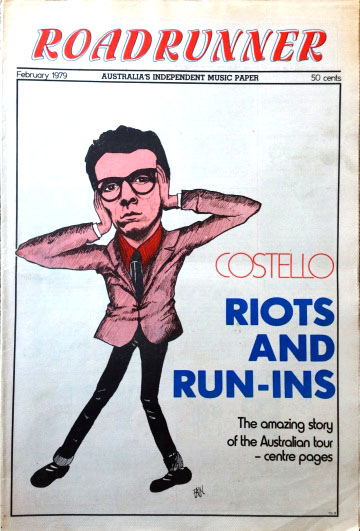

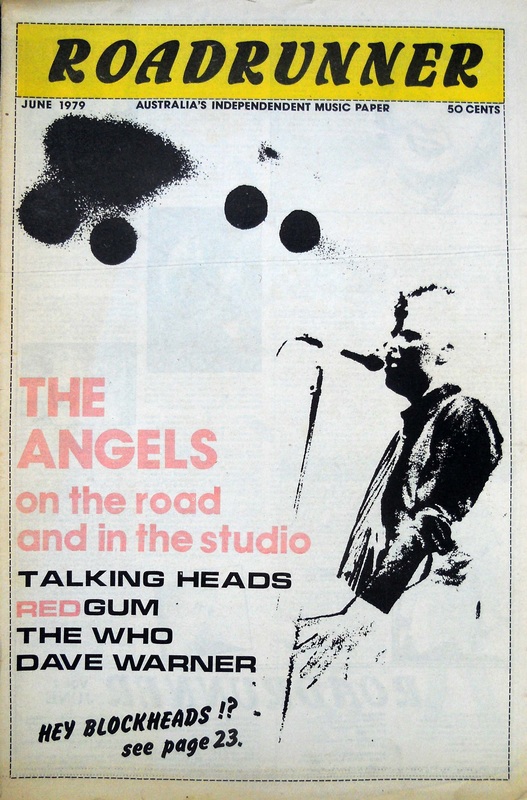

(Juke never really recovered from its damning review of the Saints’ self-pressed debut single “Stranded,” which was received rapturously everywhere else around the world, including by RAM and even Rolling Stone in Australia, and which launched the band’s seminal career. Now, it has to be said, Juke-bashing was always a popular sport, and I don’t want to just be gratuitous about old rivalries; I want to take this opportunity to lay to rest any old lingering misapprehensions. But even in hindsight things still look much the same. The NME earned some infamy when it bagged the first Clash single, describing them, as I still recall, as a garage band that should go straight back to the garage, but that was an anomaly in the NME’s otherwise punk-smitten agenda and one it quickly recanted on. But after Juke ran Jamie Dunn’s review of “Stranded,” it set a blinkered, reactionary tone that might have well-suited Michael Gudinski and Glenn Wheatley, but took the magazine itself years to overcome. As Bruce Milne said in an interview with Mess+Noise in 2011, to tie in with the rediscovery and digitization of Fast Forward, describing the surrounding music-press environment at the start of the 80s: “Well, I was writing for RAM, and so were Stuart Coupe and Clinton Walker. Juke was a lost cause though. I wish I had the Juke review of the first Saints single. They were so out of touch, talking about a record that everybody knew was revolutionary as being badly recorded and somehow related to a rock’n’roll revival. What planet were they on?” Well, it can now be revealed, exactly what Jamie Dunn said about “Stranded,” in the 25/9/76 issue of Juke. He wrote: “If you think the name of the label’s bad you should see it…uggh! God only knows where, what, when or why the Saints came marching in. I can imagine the Stones doing demos this bad when they’d just left school. The mix is bad, the playing’s bad, the label’s bad, the name of the band’s bad, but as they say… we all got to start somewhere and for the Saints this is a start but only just.” Thereafter, Melbourne’s exploding post-punk underground, one of the most vibrant in the world at the time, got very short shrift from its signal hometown mag, which instead seemed to prefer acts like Stars and the Little River Band. It wasn’t till the mid-80s, when the likes of Ian McFarlane and Mick Geyer started writing for it, that Juke started catching up with the scene around it, and started getting taken a bit more seriously. By which time it was virtually all over bar the shouting, really.) Punk was a critic’s creation as much as anything, and certainly, it was the punk uprising that gave local music writing a great shot in the arm otherwise. In 1978, two new magazines were launched, Roadrunner, out of Adelaide, and Melbourne’s Bottom Line. But it was Roadrunner that survived, even despite its (initially) remote Adelaide base, because it was so much more new wave than Bottom Line, which was as old wave as Juke. Roadrunner was a collective of former fanzine writers headed by Stuart Coupe and Donald Robertson and including myself and Bruce Milne. RAM was always more prepared to do local covers than Rolling Stone and by the start of the 80s, in addition to its stalwart championship of pub rock superstars like Chisel and the Angels, it was unafraid of hot new new wave acts whether, say, the Sunnyboys, the Models or INXS. Rolling Stone didn’t do an Australian cover between its first in 1975, the Skyhooks, and INXS in 1984; Men At Work in 1982 came via the US. But after Stone went monthly in 1980, it began an ascent that would see it first peg back RAM, then outlive RAM, and then outlive everyone to survive to this day. |

|

The game wasn’t so big in 1980 that I couldn’t be a star freelancer for all three opposing papers RAM, Roadrunner and Rolling Stone. Nobody paid retainers; in fact, I don’t recall that Roadrunner ever paid at all (to read RR-mainman Donald Robertson's recollections, go here). Money was clearly not my motivation. I was on the dole and I had a part-time cooking job. I was free, young and white. I had no thoughts for tomorrow.

|

|

Moving into books, then, was again not so much professional or creative ambition as I could just see the need for certain stories to be told. Fortunately it was a time when publishing was opening up to all the more alternatives. De-regulation generally was inciting an economic boom.

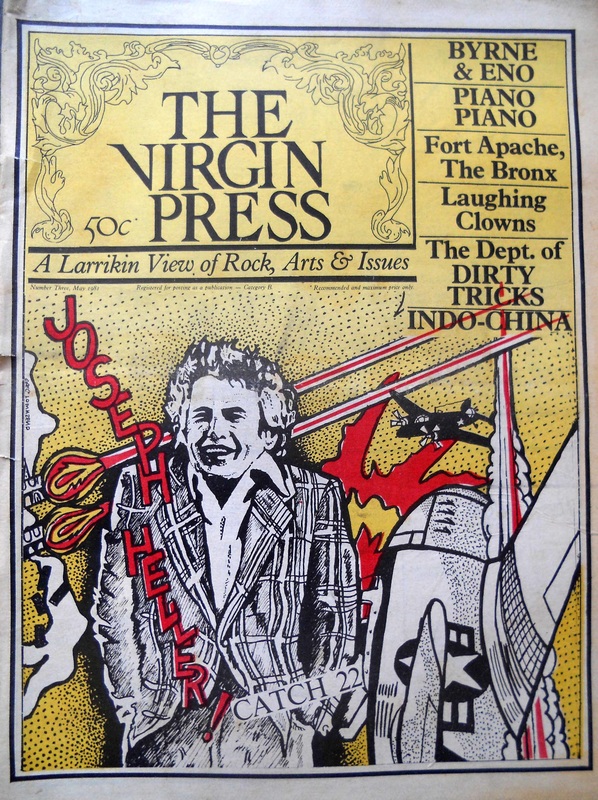

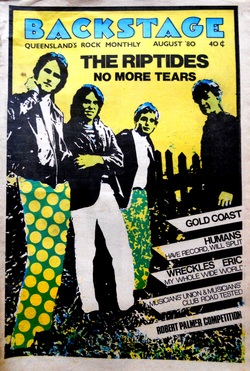

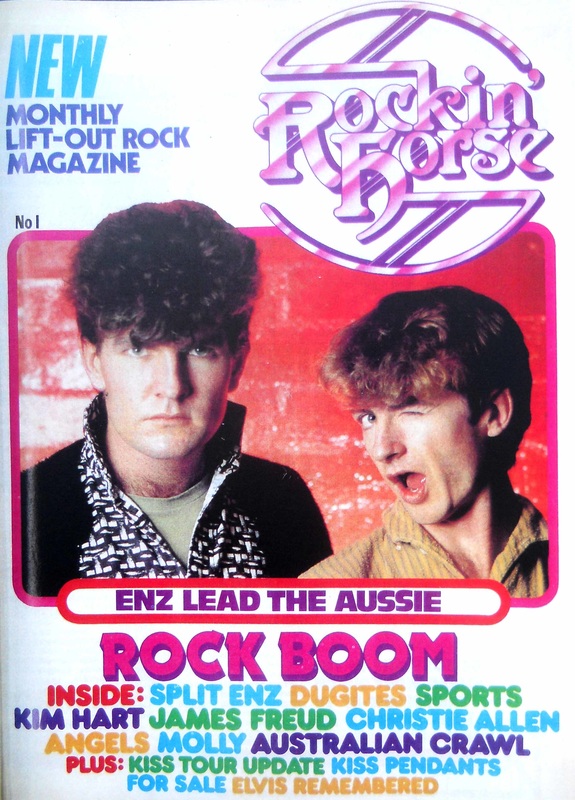

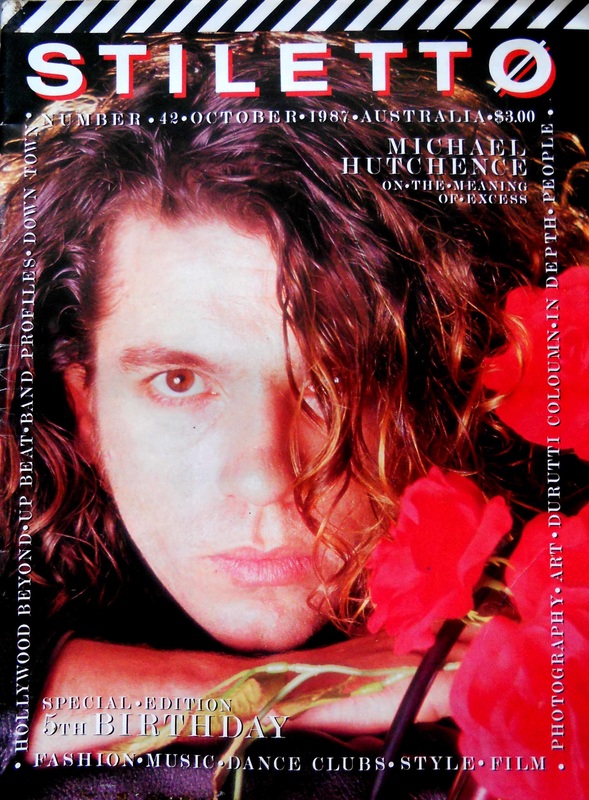

Glenn A. Baker joined forces with Stuart Coupe and for Bay Books in 1980, they produced The New Music, a sort of illustrated encyclopaedia of the new wave aimed at an international market and which, even despite tending to read like recycled press releases, was indeed published in the UK complete with its Australian content. Baker went on to join Wild & Woolley to write The Beatles Downunder. Wild & Woolley had had a hit with Up and Down with Rolling Stones, the memoir of Keith Richards’ drug dealer Tony Sanchez, which sat quite comfortably on its list alongside Ron Cobb comics and marijuana growing guides. I joined them too to do Inner City Sound, which was really just an Australian fanzine best-of, like the Sniffin’ Glue scrapbook The Bible, or Caroline Coon’s 1988. The early 80s was a bit like the early 70s all over again but with short hair, stovepipe pants instead of flares, and on speed, not pot. Roadrunner stepped up to a Sydney base, and new magazines started popping up all over the place: Virgin Press, Backstage, Vox, Stiletto, Record Buyers Guide. Some even lasted longer than a few issues. Bruce Milne’s Fast Forward was an international trend-setter as a cassette magazine, sort of the forerunner to today’s podcasts, and it helped forge Australian music's primacy in the eventual formulation of grunge (seminal Seattle label Sub-Pop started as a zine inspired by Fast Forward and which featured many Australian acts). Rock was intersecting with fashion and post-modernism. Trade journals like Sonics and the APRA Magazine were born. |

|

I could write for any of the rock magazines I trusted to pay me and for newspapers, the Adelaide Advertiser and the Age, and for the Sydney fashion/art/music glossies, Stiletto and Follow Me, even for skinmags like Playboy and Penthouse. Later I worked a bit for Inside Sport too (sports journalism, of course, being barely a rung up the ladder from rock journalism). When my friend, Age journalist Richard Guilliatt was appointed to transform the paper's Friday gardening section into the EG (Entertainment Guide), it became arguably Australia's first such weekender preview supplement, and I contributed scores of music and film features for many years. In 1984 I edited my second book The Next Thing for Kangaroo Press. I was so anti-gonzo that it was collection of straight Q&A interviews, with the contemporary acts I thought were important: Nick Cave, the GoBetweens, the Laughing Clowns. The Machinations, Celibate Rifles, the Reels. Pel Mel. The Triffids. Allow me to indulge myself by listing the contributors, which strikes me now as something of a roll-call: Frank Brunetti, Stuart Coupe, Toby Creswell, Richard Guilliatt, Peter Lawrance, Mark Mordue, Ed St.John and the late Michael White; if they were all men, the all-important photos were taken by Francine McDougall, my lenswoman of choice after Linda Nolte went off to Tibet in search of the snow leopard. The contributors were unpaid but I split the small royalty advance with Francine. We had a great launch party at the Chevron in Sydney starring the Triffids, Tex Deadly (nee Perkins) and the Dum-Dums, and bits of Died Pretty, the Wet Taxis and the Celibate Rifles, and the book was never mentioned again.

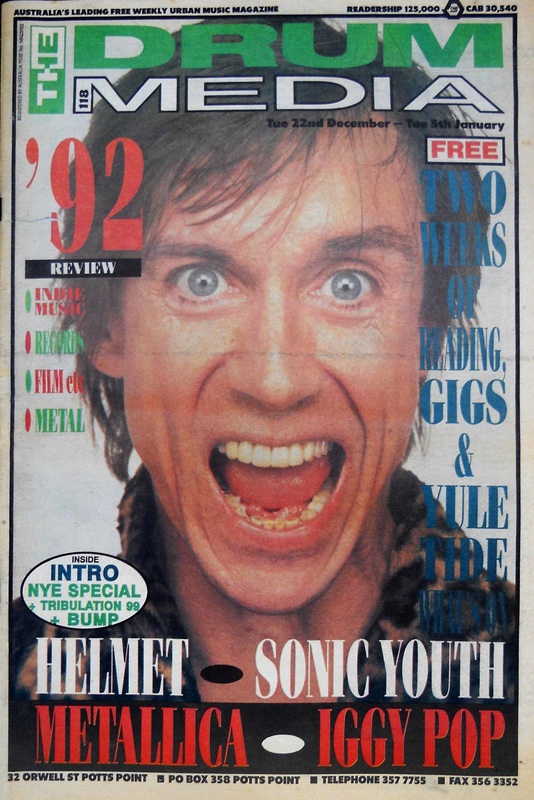

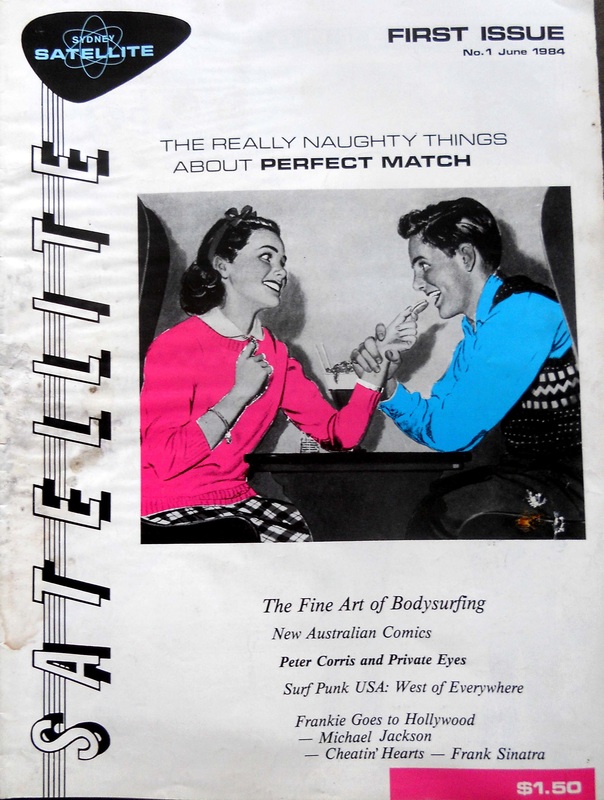

Doubtless more important though than the magazine start-ups that flashed and burned, was the birth of the free street press. The roots of the regional street papers were first planted at the end of the 70s by the Sydney Shout and by the handy pocketsize gig guide Tagg, which started life in Melbourne, published by the Toorak Times, and quickly expanded to Sydney too. By 1981 when On the Street was launched in Sydney and Time Off in Brisbane, it was game-on; both Time Off and the Drum Media, which is what Margaret Cott morphed On the Street into after an ownership-split in 1990, outlived most of the national semi-glossies, and in fact only died relatively recently in the face of the inexorable rise of the internet. |

|

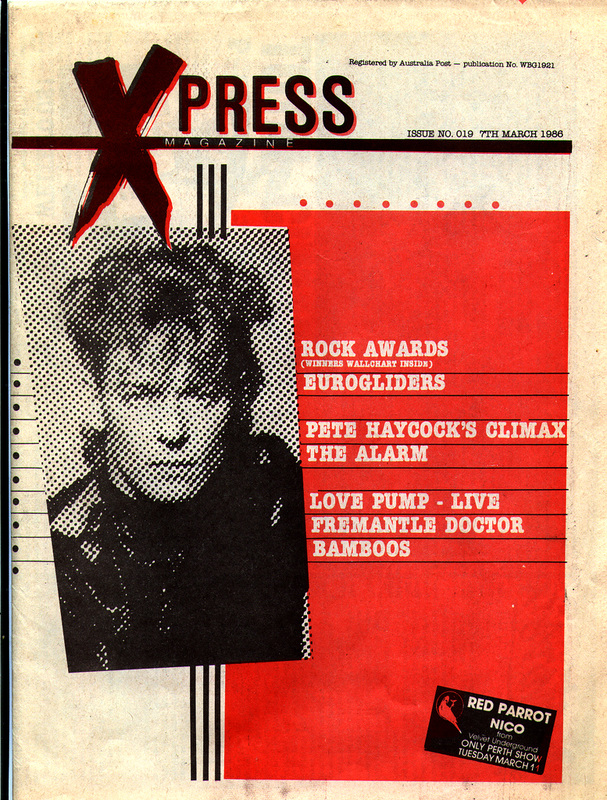

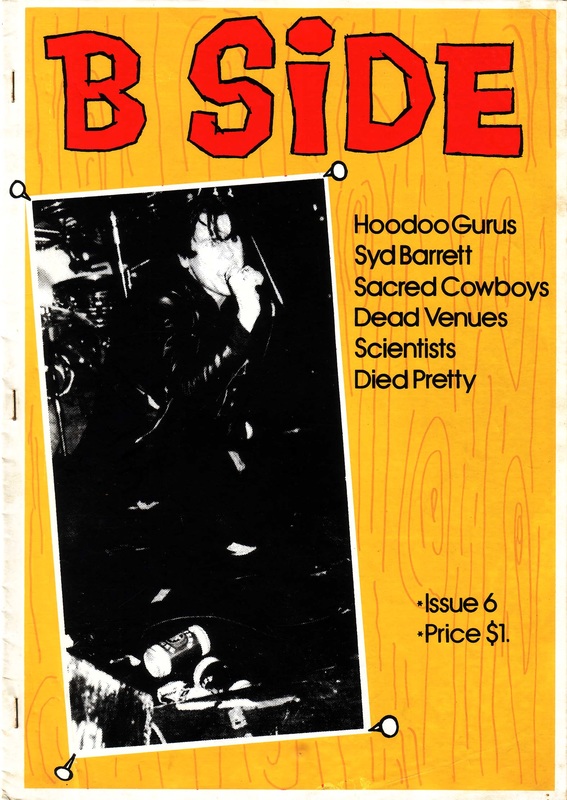

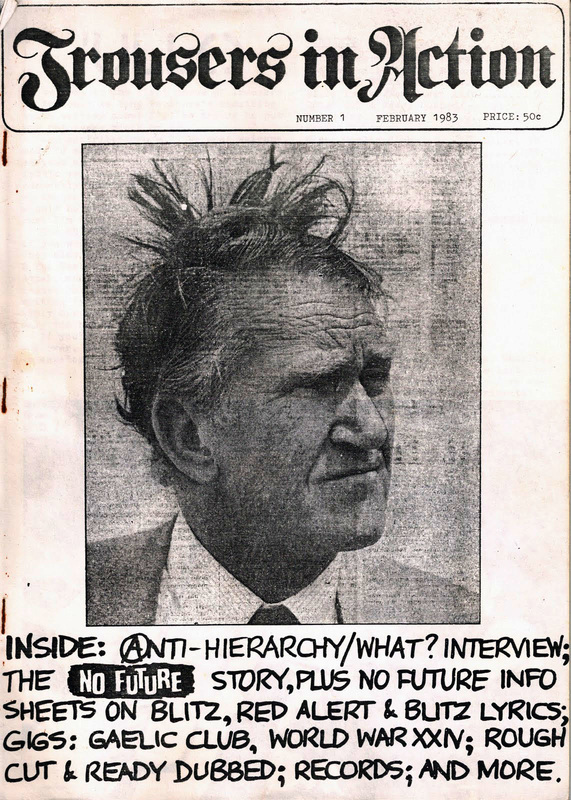

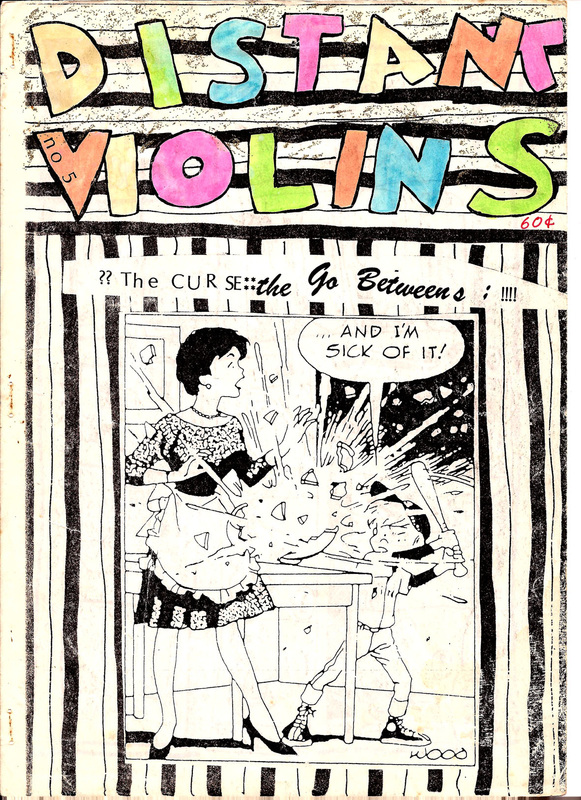

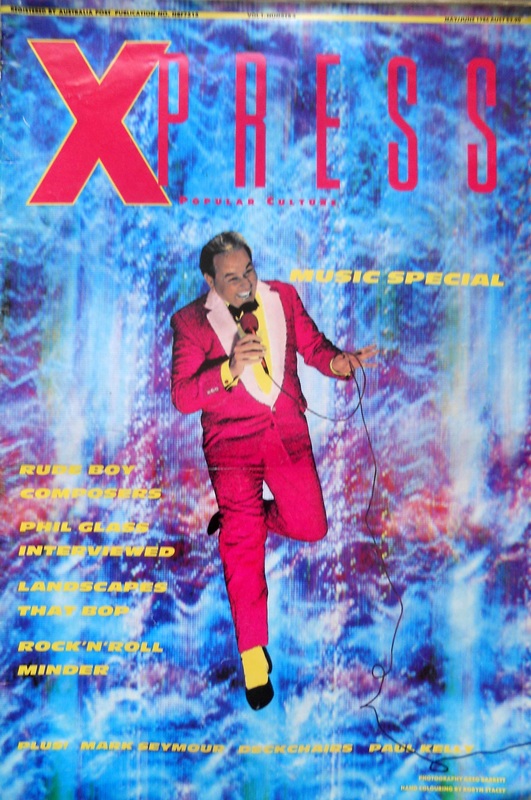

Perth’s X-Press would follow in 1985, and Melbourne’s Beat in ’86, with In-Press soon after, and again, all these thrived for several decades, tapping into a stream of advertising that hadn't existed previously. But the street papers were a blessing and a curse, a blessing because they hooked so directly into local music communities and provided them with invaluable support, a curse because of a tendency to advertorial at worst, and pretty average writing at best. In terms of creative writing and critical acuity, long-standing 80s’ fanzines like B-Side, Distant Violins, and Bruce Griffiths’s Trousers in Action serve as a more penetrating record of the period.

|

|

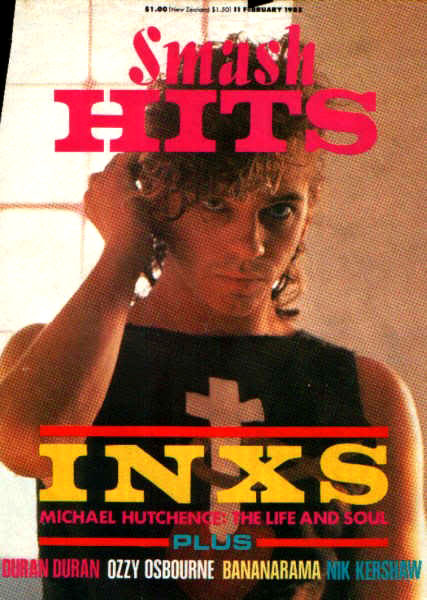

The four types of outlets for music writing – the street press, fanzines, national magazines, and the general/mainstream daily papers and monthly lifestyle magazines – determined the way writers could juggle a career, or as I’ve always called it, anti-career. There was never many staff jobs to go around either way. The lot of a freelance journalist was precarious and stressful. Like being in a band, you can’t go into it expecting to make money. And so, by way of an example, David Nichols would edit the new Australian version of Smash Hits as a dayjob in the 80s, and edit Distant Violins for love. Nowadays, he earns a crust as an academic, and publishes books for love. It becomes vocational really, just as it is for most supposed-career writers in this country, where the numbers, the margins, make it all so tight.

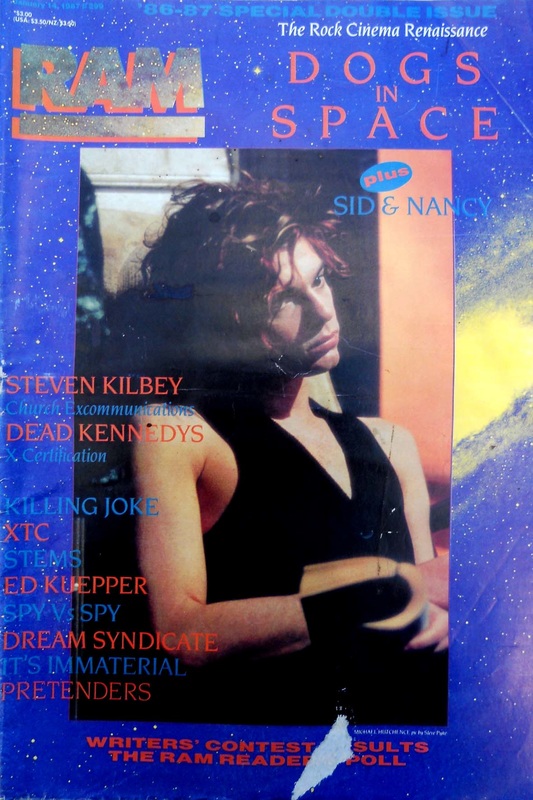

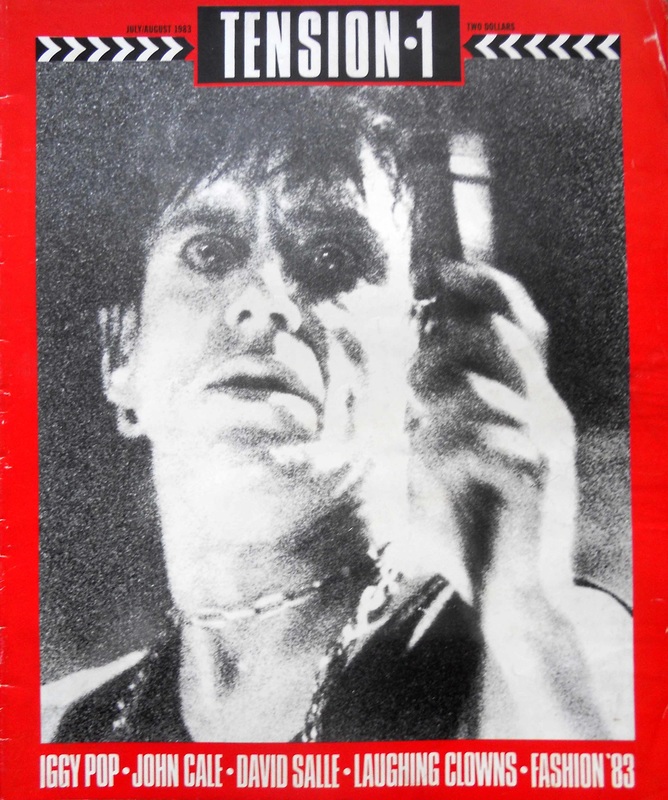

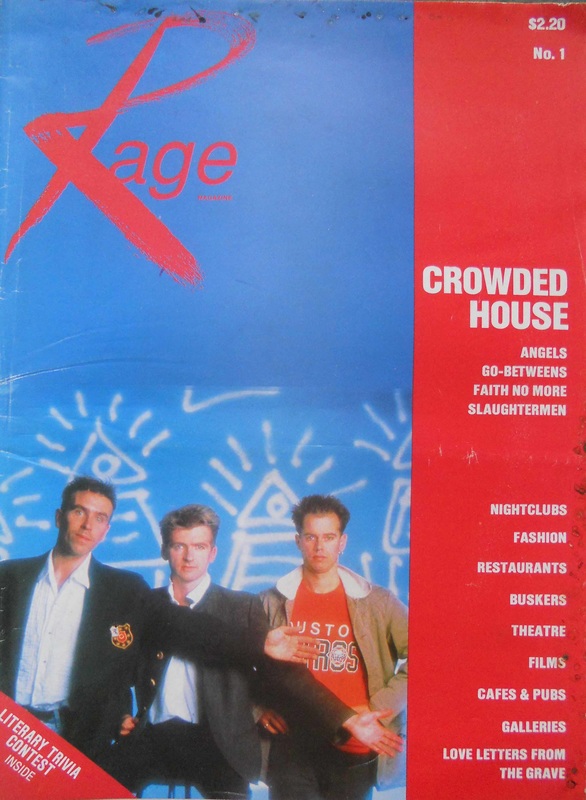

The rise of the regional street press hastened the fall of the lesser nationals, and finally, in 1988, RAM. The sad death of RAM was at the end of an era. The Berlin Wall and Wall Street both fell in the late 80s. Countdown was axed in ’87. The corporate rock/greed-is-good era was dying. So was vinyl. The digital revolution began in the late 80s with the introduction of the compact disk. Maybe rock was dead altogether, many of us elitist rock critics thought, if John Farnham could be named Australian of the Year. I was myself turning 30 and I knew that if I kept living the way I was, well, I wouldn’t stay living for much longer. So as a starter at least I quit hard drugs. RAM’s demise left it all to Rolling Stone, virtually - at least in terms of 'serious' music coverage; one of the success stories of the period was Smash Hits, of course. The last vestiges of the 80s’ art-rock-fashion fusion were played out by Sydney’s X-Press magazine and Melbourne’s Tension, Ashley Crawford’s follow up to Virgin Press. Many other start-ups came and decidedly went. After Stiletto’s demise, out of its ashes emerged the Sydney free weekly 3D World, which was like a club culture equivalent of On the Street/Drum and just as successful, at least, again, up until the incursion of the internet. |

|

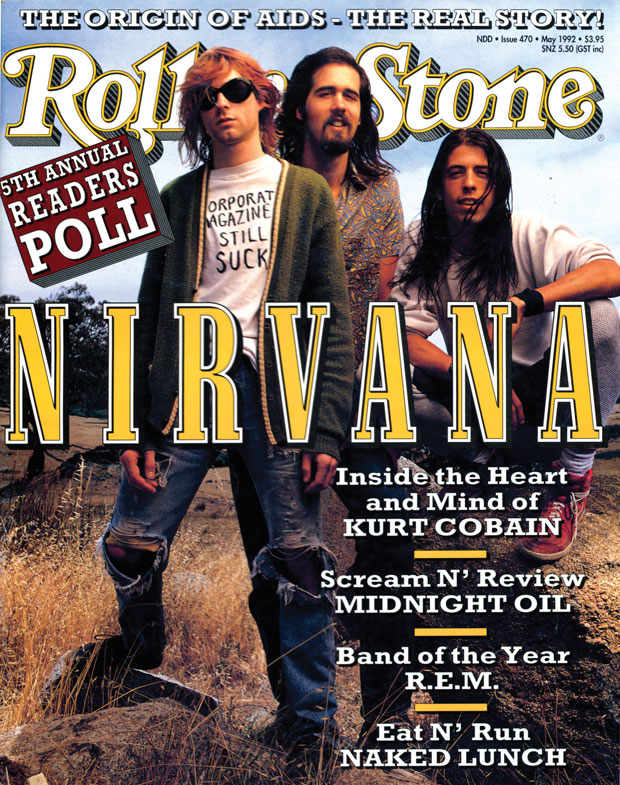

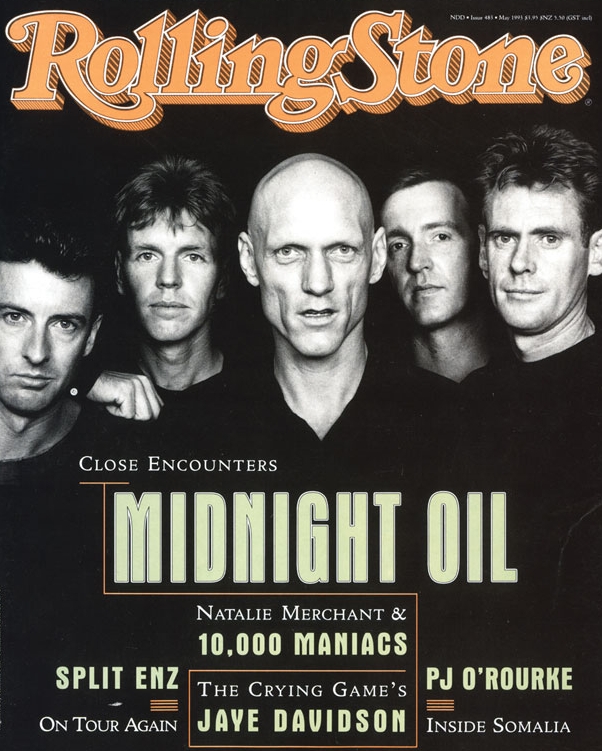

Yet though Juke would limp on to 1994, the indisputable boss at the decade’s turn was Rolling Stone under Toby Creswell. An increasing number of Australian covers never sold as well as the internationals, but the commitment to good Australian music and good writing was never in doubt.

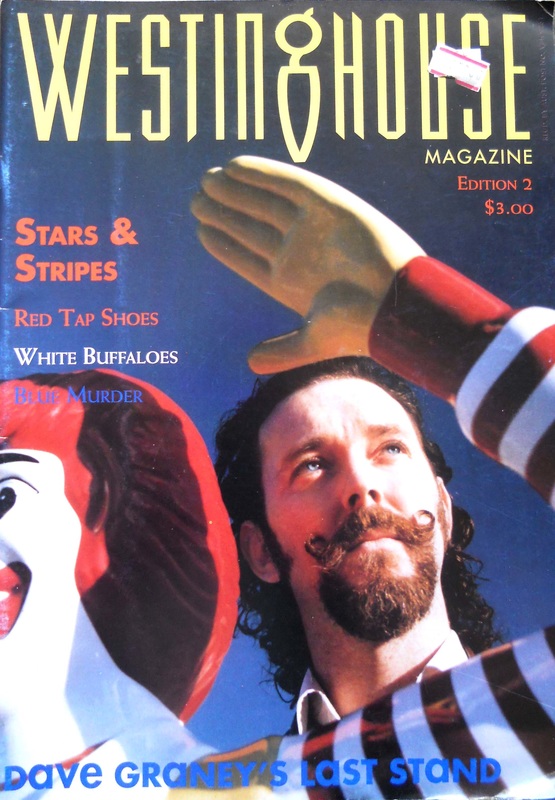

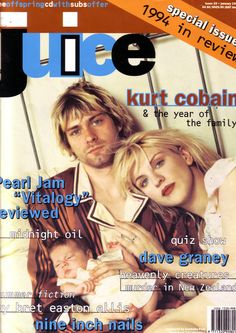

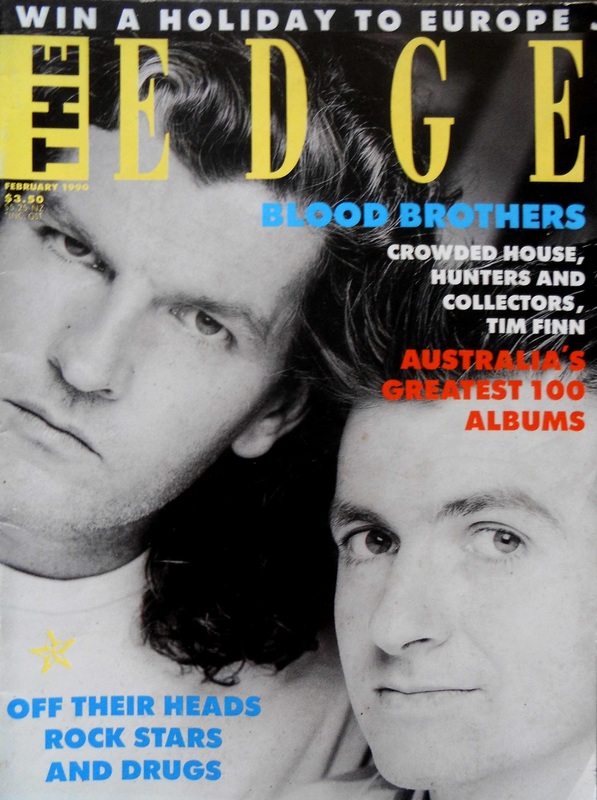

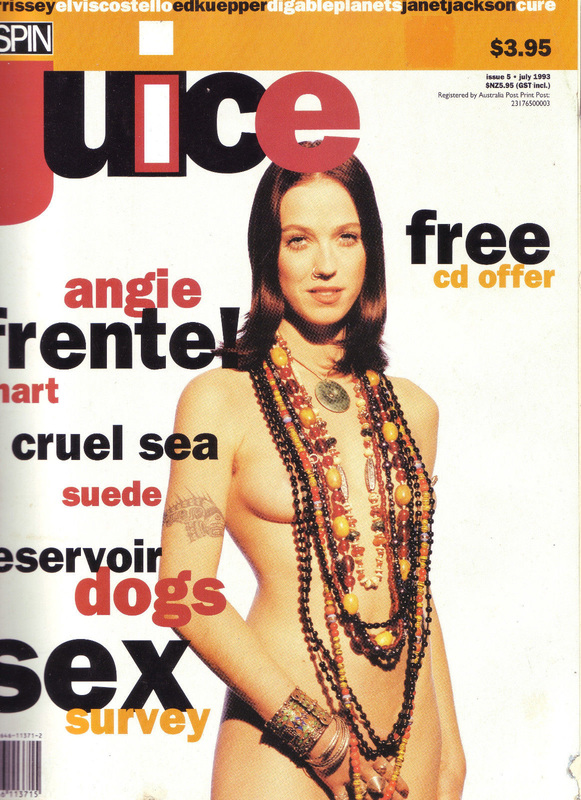

“By 1992,” the ever-astute Mark Demetrius wrote in the Stone in ’94, “the CD ‘revolution’ was complete.” The CD was just the thin edge of the wedge. Hip-hop, a form Australia initially had little purchase on in the 80s, was making new music out of old records, based on new digital sampling technology, and it was related to a whole new push in dance music – pre-EDM – that would effect the most profound shift in the sonic architecture of pop since the rise of rock itself in the late 50s. But it was in 1992 that the Great Rolling Stone Split took place, a controversy as bitter and divisive as the break-up of the GoBetweens in Sydney only a couple of years earlier. Relationships had so soured between Toby and Stone co-owner Phil Keir and his wife Lesa-Belle Furhagen that in September, Keir had security frogmarch Toby off the premises. Kerr took control of the company and installed Kathy Bail as editor of Stone, and Toby and Lesa-Belle went off together to launch Juice magazine. I served only briefly as Assistant Editor on the ill-fated Edge magazine, which was the brainchild of Stuart Coupe and former Dolly editor, Julie Ogden. Nobody had ever given me a staff job before because, I can only presume, I was considered too much of a loose canon to be trusted to toe the party line. But the gig didn't last long, the magazine failing to stick to its guns and soon enough folding. I returned to again straddling the two major competitors in the market, Rolling Stone and Juice, but my interests were shifting, onto writing long-form books. I was happy to leave local grunge to young fellas anyway, like Dino Scatena, Craig Mathieson and Andrew Stafford. because they were out there doing it, living the Life that I didn't want to any longer. |

|

Through the 90s, Rolling Stone and Juice vied for market leadership, balancing a steady diet of Brit-Pop, Australian and American grunge and global electro dance music. The rock/EDM split was only one in music; the whole market was diversifying, fragmenting, globalising and tribalising, as demonstrated by new genre titles like Hot Metal and Rhythms. Rhythms was and still is roots/acoustic/heritage rock-oriented, related to the great new trend of music media in the early 90s, lavish retro rags like Mojo, which trade in deep rock history. That rock history was now a newsstand staple says a lot in itself.

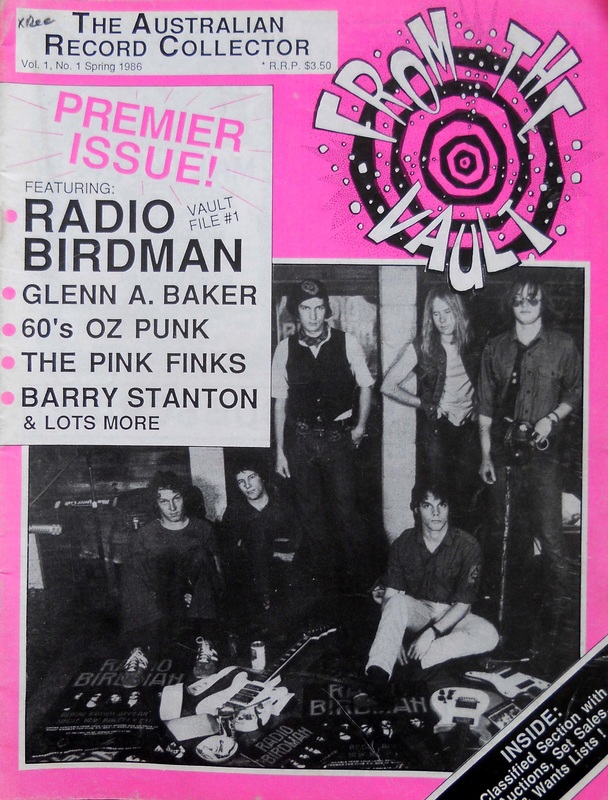

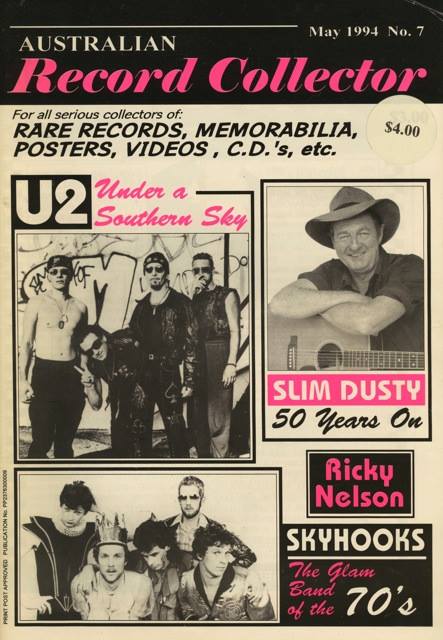

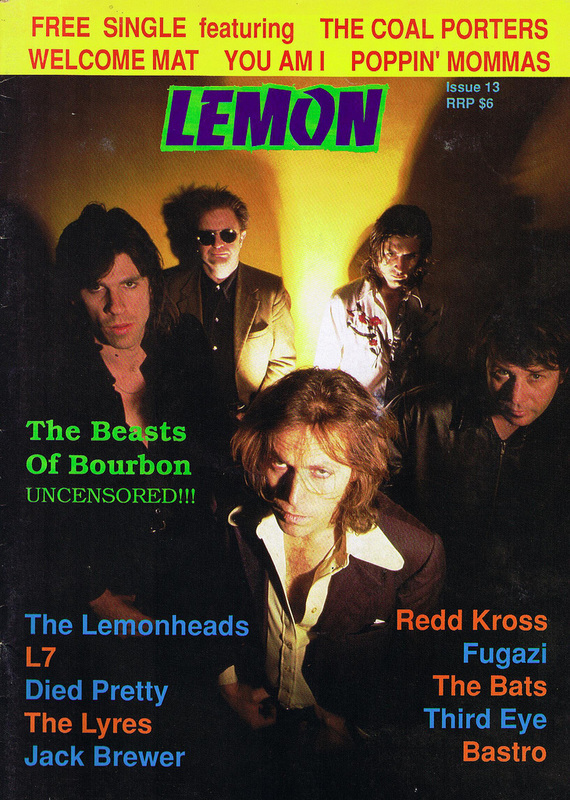

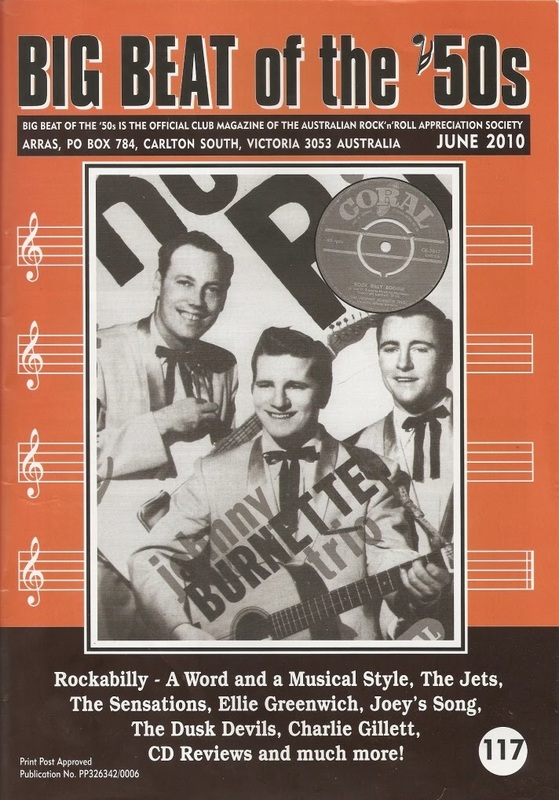

The street press grew and grew. The fanzines that described the transition into the 90s, from vinyl to CD, were Perth's Party Fears, Resistant Harmony and Louise Dickinson's Lemon; retrozines for collectors like From the Vault, the enduring Big Beat of the 50s, and Ian McFarlane's Freedom Train and Prehistoric Sounds described where the music had come from. The daily papers were becoming increasingly Entertainment or Arts - or more to the point, Celebrity! - oriented. Even the academic world stepped up, with the launch in ’92 of the Australian music studies journal Perfect Beat, around the same time that its founder Phil Hayward edited his first book, From Pop to Punk to Postmodernism. Everything seemed post-something now. |

|

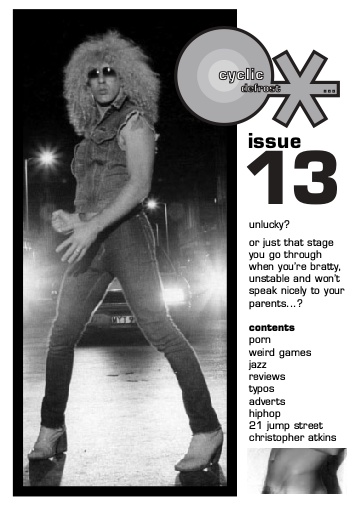

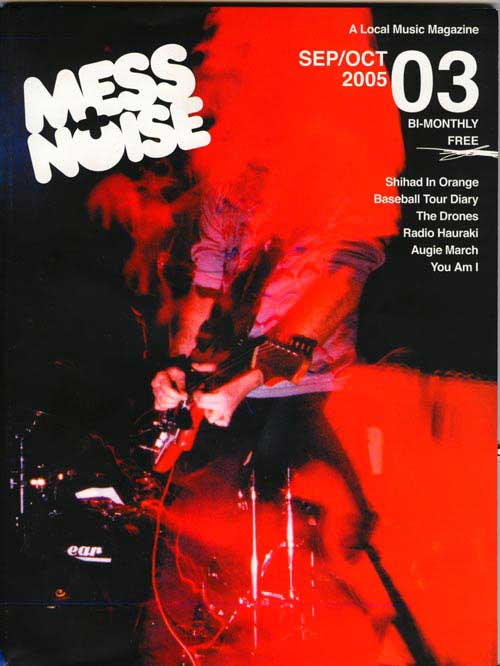

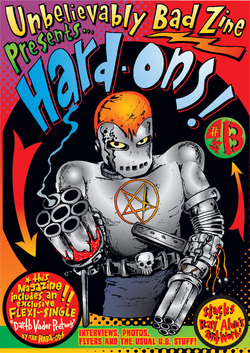

In the late 90s Cyclic Defrost was born as photocopied electronic music zine, and it quickly matured into what might more rightfully be called a journal, with its quarterly schedule, and high-quality writing, design and printing (now possible with digitisation making it so much cheaper and easier) – and eventually, Australia Council logos in support. Mess + Noise epitomized this same trend from a more Melbourne/rock angle. Starting up in hard copy in 2005, Mess + Noise has only survived by making the the same transition Cyclic Defrost did, to an online webzine. Unbelievably Bad was another vibrant zine that also survives now online. And since then, with the demise of Juice and with the exception of Rolling Stone, and putting aside the erratic J-Mag, and if you don’t count Rhythms, there hasn’t been another national music monthly since.

|

|

I was frustrated because mainstream media was clearly no place I could pursue my new, even more apparently marginal interests.

Which is about where I check out, or at least jump off the freelance treadmill. I started producing books and babies and then CDs and TV. Popular music would become the virtual test-case for the whole new online world of unlimited free access. |