| Just back from my third visit in two years to Indochina (is it okay to still say that? I do so because it covers Cambodia and Vietnam, both of which I went to this time), and everything about the place continues to intoxicate. Concluded the trip with a quick holiday in Vietnam (a week by the beach on the beautiful island of Phu Quoc, which looks like it could become the next Ibiza, or Bali; followed by a few days back in Ho Chi Minh City before flying home), but more pertinent here is the week spent in Cambodia, in Phnom Penh and Kampot, for the 2016 Kampot Writers & Readers Festival. As just the second such annual event, and the first of its type in Cambodia, organised by Julien Poulson and a handful of dedicated volunteers out of Julien’s KAMA (Kampot Arts & Music Association) café in the southern coastal town, the festival was definitely a case of organised chaos – as I’ve come to appreciate so much in Cambodia seems to be! – but even for all the odd grumblings on that basis as well as a couple of other moot points, it has to be counted, I think, a great success. And given that it will doubtless learn much from its numerous (what are still) teething problems, I hope and expect it will carry on and indeed thrive. But I am pretty sure that in order to do that, it will need more funding and more staff… Certainly I had a great time myself, and everybody I encountered, whether locals or barangs like me, seemed to enjoy themselves too. There were so many events and people present it’s hard to do justice to them all, but perhaps before going any further I should offer thanks to a few of the volunteers I relied on and happily got know a bit, most notably Kek Soon, Poz, Andrish Saint-Clare, Billy from Texas and of course the ubiquitous Tony Lefferts. Thanks too to Steve Porte for most of the best pix that follow here... |

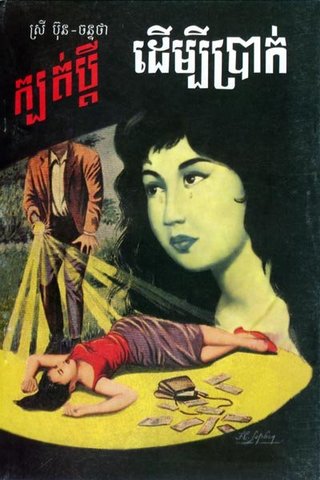

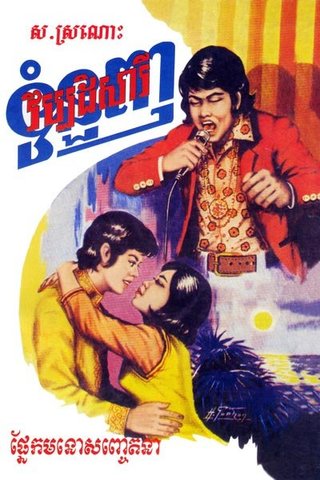

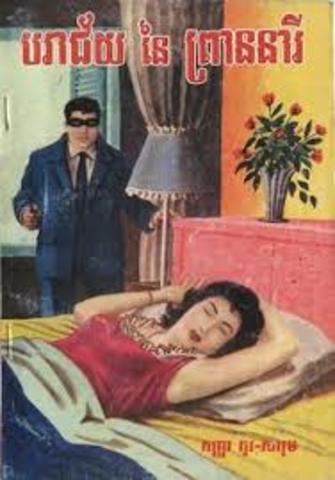

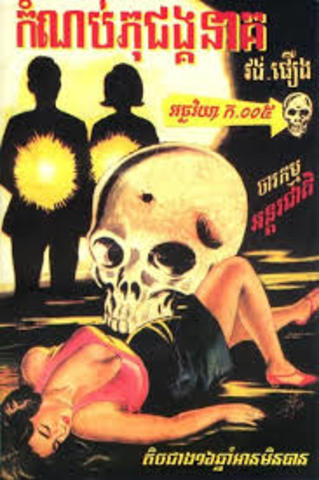

| A few items that ran in the local Cambodian press in the aftermath of the event (here and here) touch on both its successes and shortcomings, and if its organisation – its scheduling and traffic-control, so to speak – are largely technical problems that can easily be surmounted with a bit more money and personnel as I’ve suggested, the question of local content is a bit more vexing, but one, again, I believe, that can and will come into its own as the festival matures. Cambodia, after all, is a poor country that still has very low literacy rates, and which has a limited tradition in literature both pre- and post-Pol Pot. But as it emerges as a modern nation with more young people getting access to education, at the very least learning to read and write, the books will start to come… they already are, in fact, if only as yet in a trickle; but with more and more writers and entrepreneurs, notably especially young women, developing means within traditional publishing routes (ie, books) and beyond that into the contemporary online world, and with events like this one, the word-count will start to build up… I was myself totally inspired, as I said on the occasion, to attend one event convened by American writer and editor Sharon May that shone a light on the young – many very young! – Cambodian writers like those she’s so far co-edited into the anthology, In the Shadow of Angkor. It was totally inspiring to hear them speak of their lives and writing that seemed to have had so many obstacles to overcome… Like the way Thavry Thon had come from a small island on the Bassac River, and been fortunate enough to get an education – no mean feat in a country where girls are discouraged from doing that – and whose initial ambitions were just to get to the city and maybe fly on a plane; but who has now far surpassed that by becoming a globe-trotter with her first book A Proper Woman about to be published next year. Mak Suong is a bit older and became infamous with the publication of his novel Boyfriend, the first Cambodian book to even broach the topic of homosexuality, and he has to be counted as a success inasmuch as he’s published a number of books that I can only describe as looking like pulp fiction; turns out, as I dug a bit deeper on this topic, Cambodia has, if anything, a fair bit of its own tradition in pulps and comics, and I will yet be digging even deeper into this. |

| When I took a turn to say a few words at this session, I said that there was as much in their stories that was familiar to me as unfamiliar. And so I did try to stress that to struggle as a writer is not unique to Cambodia. Some had already learnt the hard way, like Heng Borin, who started out thinking all writers get as rich as J.K. Rowling; and who then, even when he published a hit book in Blood from Hell, lost out big-time to pirates and an unscrupulous publisher (pirated books are certainly all I’ve ever seen in street-markets and bought in Cambodia, the same as CDs and DVDs). If young Cambodian writers have to support themselves, I told them, through day-jobs like writing advertising copy or selling noodles, well, I said, that’s not very different to Western writers like myself who’ve driven cabs, written ad copy or worked as a cook or a cleaner! There was, however, a bit of a gulf between these young Cambodians and so many of the barang that otherwise studded the festival. I was one of the few barangs at the session recalled above. But literary festivals are international affairs and certainly it’s a point of frustration for me that once past the fact that Australian literary festivals are mostly all about the sanctioned highbrow-elite capital-L literature, audiences will flock to see the latest sensation of the month from overseas and ignore the unfashionable schlepper from next door (if he’s been lucky enough to be invited in the first place!). Also overlooked a bit too, I think, is the expanding syndrome of the once-exiled refugee Cambodians who are now coming home to roost, or rather to give something back, what with all the more education and experience they’ve gained in the West, mainly the US and Australia. The festival was studded with such types, like Chath Piersath, Kosal Khiev, Teeda Butt Mam and volunteer-helper Poz. The festival was officially launched in Phnom Penh with a reception hosted by the British ambassador at his private residence. If I went along expecting G&Ts and cucumber sandwiches, well, that’s precisely what we got and I couldn’t have been happier. I was prevailed upon at a moment’s notice to say a few words (subbing for my pal Shane Maloney, who’d been unable to get on his flight out of Melbourne the day before), and so I did what if I say so myself I do so well – I made it up on my feet. I said that I wanted to talk about rhetoric and reality, in two instances: Firstly, in the instance of Aboriginal Australia – hooking in to the fact that I was there, after all, to present a screening of Buried Country as part of the festival’s ‘Indigenous Voices’ component – and so I said that the word ‘reconciliation’ was a virtual cliché we heard all the time in Australia but which meant little to most Australians, most of whom don’t even know any Aboriginal people. But for me it took on a reality as I got to know so many Aboriginal people, and the sort of lives they led, as a result of a near-lifetime’s work that’s gone into Buried Country. Another, the second, bit of rhetoric we hear a lot about in Australia was that we need to start seeing ourselves as part of the Asia Pacific region rather than as a subject of the British Empire or an ally of the Americans. But again, for me, this didn’t take on much reality until I started actually coming to SEA, and meeting not only ratbag expat Aussies (that got a laugh) or even Khmer themselves but also people from all over the world like were amassed in that room at that time. We can all get caught up in our own little world, I concluded, and I’m just thankful that I’ve been able to find whole other worlds not only outside my own country, like here in Cambodia, but even inside it, in Aboriginal Australia. Fortunately, since clashing schedules would prevent catching a performance by Morganics in Kampot, we got to hang out a bit with the Aussie hip-hop legend in PP, and what a pleasure that was, getting to know this great guy who just exudes so much positive energy it’s staggering. When we stumbled across a shop called Hip-Hop we had to get the photo below, even though – or especially because – the place traded only in pirated DVDs. |

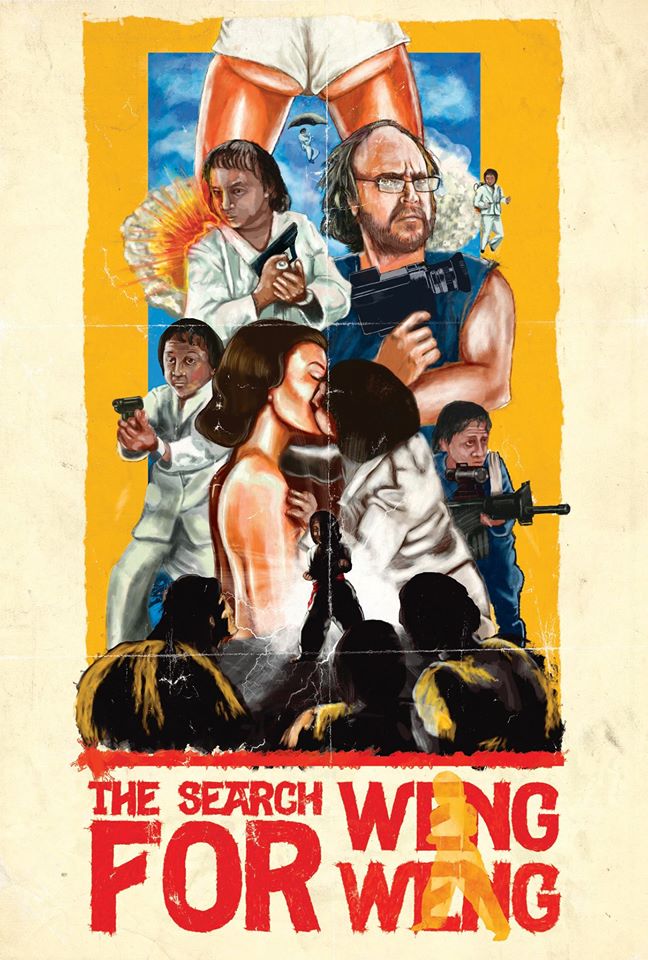

| The festival enjoyed a PP Launch-Part Two, the night after the embassy soiree, with a reception in the beautiful gardens of the beautiful Raffles Hotel, where many of us who’d flown in were treated to be accommodated. The highlight for me there was meeting Tim Page. Tim Page was a legendary Vietnam war photographer who no less than Michael Herr described as the craziest of all the wigged-out crazies and who, as such, provided some inspiration for Dennis Hopper’s character in Apocalypse Now. He was the perfect gentleman, and when he started rolling a joint, I said to him, well, I’m privileged to now be able to say I smoked a joint with Tim Page! And he bowed graciously. But then I had to add, But I dunno, is it better than being able to say it was a lifetime highlight to have smoked a joint with Lionel Rose? And he held up his hands in mock surrender and laughed, I can’t compete with that! With which he rose up on his shrapnel-laced legs and hobbled off to his next engagement, before eventually returning to Brisbane, where he now lives. What a guy! We left Raffles the next day in a convoy of taxis, mini-vans, and after just a couple of hours on some of the better roads I’ve experienced in Cambodia, arrived in Kampot, which is a typically ramshackle medium-sized town built on the river of the same name. Finding out what exactly was going on was never easy, but that becomes part of the charm, and you just surrender to the flow… The music and the movies were a big part of the show for me. I saw some great films: The Man Who Built Cambodia, a documentary about Vann Mollyvann, the signature modernist/neo-brutalist architect of the pre-Pol Pot Cambodian renaissance, a subject in which I was already interested and a film whose only real failing was that it was too short! I saw Cambodian Son, a biographical documentary about Kosal Khiev, which even as it was perhaps a tad long was still utterly compelling in its account of KK’s extraordinary life, in which, after being born in a refugee camp in Thailand in 1980, he grew up in California, went down for attempted murder at age 22, and during 14 years inside became a poet. “I am not a ‘prison poet’,” he said in the film, but he was certainly the best poet at the festival. If I was disappointed not to be able to see Golden Slumbers, a documentary about the golden age of Cambodian cinema in the 1960s, because a print could not be located (typical!), I was stoked to be able to finally see, in its stead, Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten, the documentary about the great lost Khmer music that was horrifically literally killed off by Pol Pot – it was terrific. Another film I didn’t get to see, semi-disappointingly, was The Search for Weng Weng, because it kept getting rescheduled until it was past the point of catching. I was disappointed because I’d long wanted to see Andrew Leavold’s documentary about the short-statured Filipino James Bond, but only semi-so because I got to know so well Andrew himself, that me seeing the film soon enough is just one of the aspects of a future together we know we’ve got. Andrew is one crazy mutha who takes the whole trope of cult video store guy-cum-filmmaker to a new level. He’s long since closed his Trash Videos store in Brisbane’s West End but moved on to make more movies; he was in Kampot on quick sojourn from the Philipines, where he’s working on a follow-up to his second film, The Last Pinoy Action King, a new documentary that explores the connection between vintage Filipino porn and Imelda Marcos – wow! He is also working on a film called Pub, which is an account of the St.Kilda rock demi-monde as seen through the eyes of the legendary Fred Negro – OMG!! Andrew is an iconoclast of the absolutely best and most offensive kind, and so long may he prosper… |

| Another film I missed was David Puttnam’s presentation of his classic The Killing Fields, but I did see – wasn’t going to miss – Puttnam give a talk on the movie musical, a genre in which he’s got some pretty fair form. And it was wonderful, even first thing, if an hour late, on Sunday morning. Lord Puttnam is an old English gentleman of the absolutely best and most generous kind, and he spoke with passion, erudition and humour about a cinema genre in which I’ve lately taken an increasing interest. Naturally Andrew Leavold and myself totally hogged the question time, and if you want to know what any of those questions – and more to the point, the answers – were, just ask me!... Presenting a screening of Buried Country after all that seemed a bit small beer, but it was great. Still the strongest reaction came from the handful of expat Australians in attendance, and I suppose I should count it as a success that the film can still have that same quality as degree of impact: A couple of lovely ladies from the Australian embassy I think they were, were just gobsmacked to learn of this history about which they previously knew nothing. I’ve encountered that reaction before. As I have this one: “I don’t normally like country and western,” filmmaker/journalist Tom Fawthrop told me, “but that was great.” I was almost shocked when a woman from Melbourne who called herself the Lovely Liz quickly ducked up to her hotel room and came back with a fresh new copy of Inner City Sound she asked me to sign. “It’s full of pictures of all my dead friends,” she said. She bought and I signed for her a copy of Buried Country. “It’s full of pictures of many of my other dead friends,” I told her. A panel on crime writing I naturally couldn’t miss, especially when it was chaired by the redoubtable Shane Maloney. It’s true it was all white male, but happily none of them were dead, whether Shane himself, Bob Couttie, Mark Bibby Jackson, James Newman or Steven W. Palmer. After Graham Greene, it’s virtually become a genre in its own right, the Englishman in a linen suit lost in the Oriental underworld, and so I’m keen to read some of the books I bought to see if any of them come close to Laurence Osborne’s Hunters in the Dark, which I admit is a big ask since it’s about as good a novel as any I’ve read in the past couple of years. |

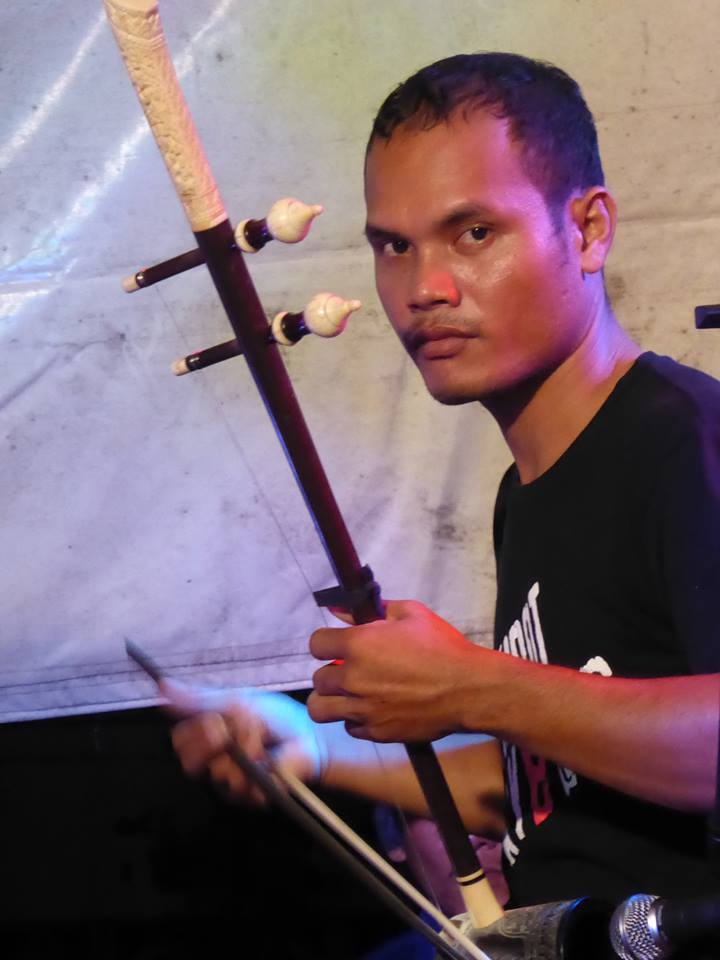

| Finally, the music. Certainly one of the festival highlights for me was seeing the Bunong Cultural Troup from Bou’Sra, or the Village People as I hope I was not too irreverent in re-dubbing them. This quartet of two men and two woman performed what I was assured is traditional Cambodian mountain music and are apparently one of the last remaining exponents of same, featuring the amazing 91-year old tribal elder Lok Ta. It’s uncanny the the way I could hear in it other mountain musics, like that from the Appalachians, thanks especially to the one-stringed bowed instrument the tro, which can sound like a fiddle; yet at other times, especially in the vocal numbers, it sounded delta-bluesy, and at other times almost Middle Eastern. It was mesmerising, and a privilege to have witnessed before such a thing might be gone forever. One of the more militant members of our mob muttered to me under his breath, It’s not enough we steal their land, we have make them sing like performing seals too! But if it’s a cop-out to say I don’t know anything about that situation, certainly I’d resist any royal ‘we’ at the best of times anyway. The couple of things I do know are: the band-members seemed to be having a ball, with the women especially away from their own performances dancing like fools to much of the other music at the festival; and I know that like everyone else who saw them, I was blown away. One sight made a real impression on me – at one of the their performances, there were two little boys plopped down in front of the stage, they looked like brothers, European, about 4 and maybe 7, and they were both watching the band transfixed, with their mouths open, and I thought, that’s great, because even if for me as a would-be musicologist this stuff still came across as somewhat exotic, for these two little boys it was already becoming normalised. And that’s got to be good. |

| If the Bunong band was an example of unadulterated traditional Khmer music, the next best stuff I saw at the festival was, to use that dreaded 1970s term, fusion. Music that mated Cambodian and Western modes. Like the Kampot Playboys, who with three barangs in the line-up comp’ing the two locals, made this unholy kriol blend of garage band with a tro in the lead instrument role, played by Nget Vy. The Bokor Mountain Magic Band are a sort of Cambodian Space Project spin-off whose front-woman Lue Thy has some big go-go boots to fill in Channthy’s, but is giving it a good shot. The other music act who were just sublime was the Messenger Band, a vocal quartet made up of young women who’ve escaped from the world of sweatshops and now want to help all their Cambodian sisters do the same. It’d be a tad cruel, perhaps, to compare them to the Indigo Girls (I was never greatly fond of the Indigirls), but with a political message as uncompromising as their harmonies are crystalline, put these girls on the Australian world music circuit, I reckon, and they’d kill it… After all that I was exhausted, and so I went to the beach for a week and I still haven’t recovered. |